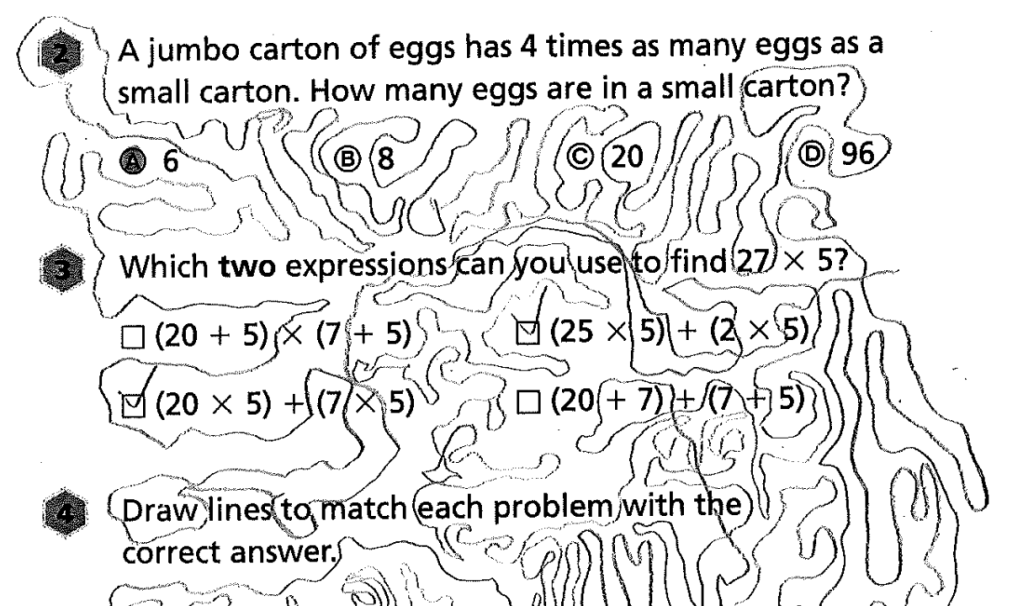

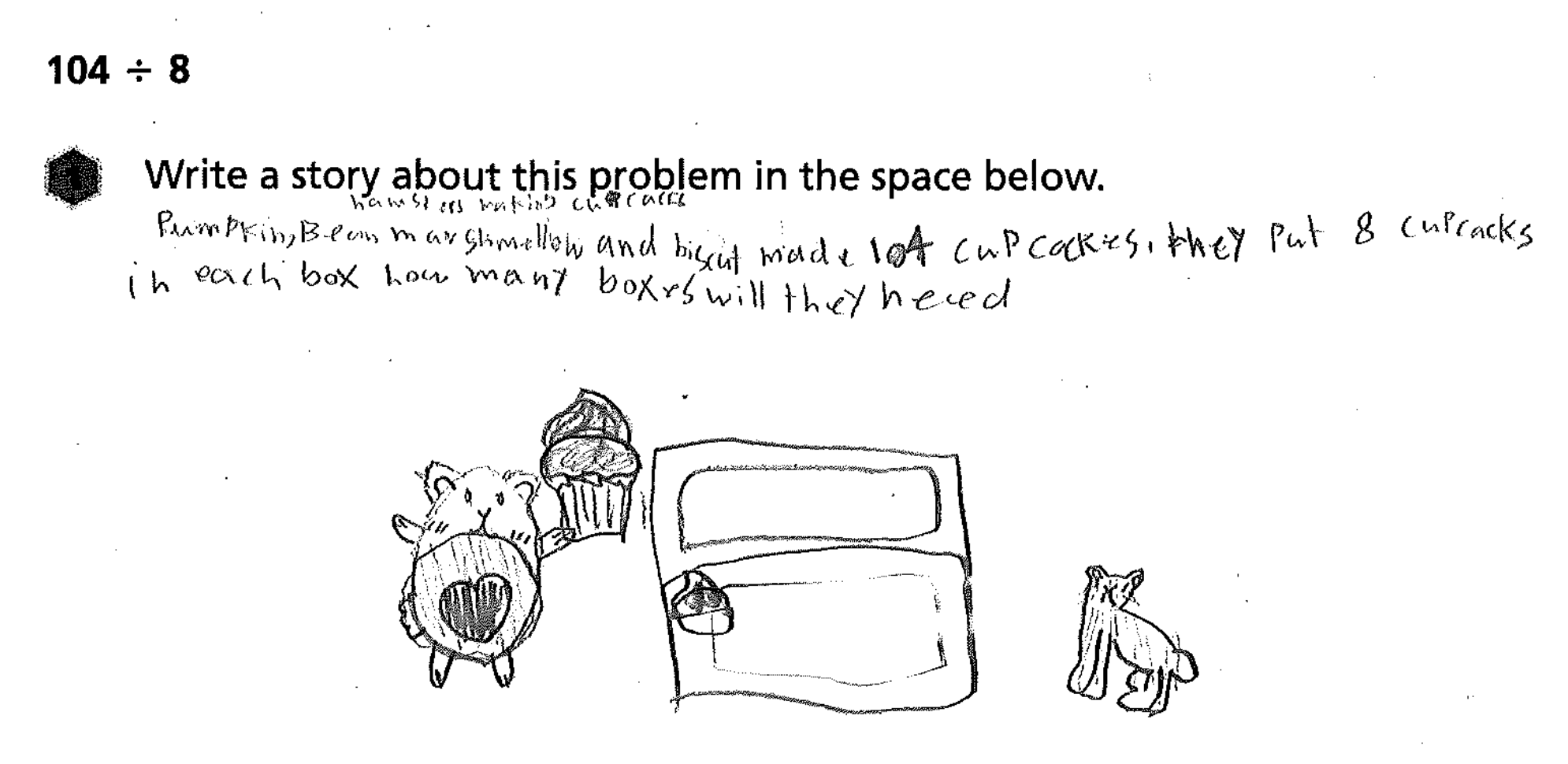

This morning in grade 4, we asked students to write a story problem and solve 104 ÷ 8. I told students that they could write what they want, but it needs to make sense and show that they understand what 104 ÷ 8 means.

I have a higher tolerance for subversive thinking than some of my lovely colleagues. For example, when a student submitted this:

JemoPeall has 104 eggs. Each nivelsnort takes 8 eggs. How many nivelsnorts can he make?

I quickly recognized the story structure, and determined that this student understands division as forming equal size groups, which is quotative division. (It could also be sharing amongst groups evenly, which is partitive division, but a story problem can only show one of those two types.) Does the story make sense? Well, it has a certain internal consistency, I will give him that. Ultimately, I’m confident that he understands this framework for thinking about division, and he accurately solved the problem. I’m not sure what JemoPeall will do with 13 nivelsnorts, but that’s not really my business, is it.

Meeting the Benchmarks

Here are a few stories that I thought met the benchmark entirely. They made sense, and they showed an understanding of the meaning of division.

Story #1:

Bob has 104 stickers. Jeff has 8 times less stickers than Bob. How many stickers does Bob have?

This story is fascinating to me, because it doesn’t show partitive or quotative division. This is a multiplicative comparison story that is written in a way that suggests division. Yesterday, we worked on a multiplicative comparison problem about the length of a Murphy’s sphinx moth’s proboscis, so I’m not shocked that this student decided to continue with this line of thinking.

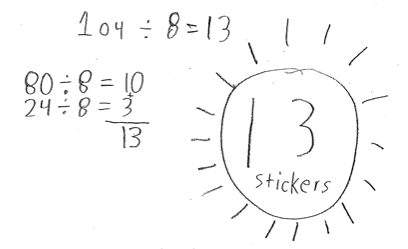

Here is his student work, by the way. He decomposed 104 into 80 and 24, and then divided by 8 to get the amount that is, proportionally, eight times less.

Story 2:

Bob had 104 colored pencils. He sorted them into 8 groups. How many are there in each group.

So many kids go through a ‘Bob phase,’ a time in their lives in which there is perhaps nothing funnier than the name Bob. I think of third grade as peak Bob Phase time, but there seems to be a sizable cohort of Bob Phase kids in fourth grade right now. This story isn’t inspiring, but it shows that this child understands division as making groups, and the story doesn’t spark too many questions of feasibility. I may not know why Bob is sorting his colored pencils, but it seems like a plausible afternoon activity for Bob.

Story #3:

One day, Timmy was making pies with 8 blueberries in each pie. How many pies can he make until he runs out of 104 blueberries.

I mean, it’s a little odd to mandate such a specific and seemingly arbitrary quantity of blueberries per pie, but I don’t know what kind of instagram-worthy constraints baker Timmy is under.

Story #4:

Sunny has 104 sun biscuits. She wants to sell them in bags of 8. How many bags does she need?

This child understands both division and marketing. (Sunny is selling sun biscuits? Great name. That had to have been workshopped with a focus group.)

Story #5:

There are 104 flying tomatoes and you need to catch them in potato sacks of 8. How many sacks do you need?

This is another one where I might have a lot of questions if this were happening in my life — what am I going to do with all of those flying tomatoes? — but it shows that she understands division as making equal size groups, and putting them in potato sack seems like a reasonable location to store these things. (Also: are flying tomatoes doing good? Evil? What features of their body facilitate flight? Is the stem an integral part of this?)

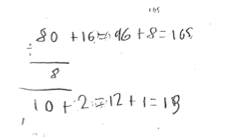

Here is Flying Tomatoes’ work on solving 104 ÷ 8.

She started with 80 (10 groups of 8) and then added on additional groups. While her equation at the bottom of the page doesn’t preserve a concept of equality with the equal sign, it does show me how she is thinking multiplicatively, and I celebrate that!

Examining the ‘Almost Theres’

Most of the students wrote stories offered a clear example of a division context. The stories that are not quite meeting the benchmark — there’s a syntactic issue, or they wrote something that connects to 104 ÷ 8 — is perhaps more interesting to me. With these students, I think about what I can determine about their understandi

For example, check out this brilliance:

Story #6

Jack robbed a bank and got $104. He gets caught and they take 1/8 of his money. How much money did Jack lose?

This shows that the student is thinking about division by 8 and multiplication by as equivalent operations. Amazing! It feels like it models

rather than

but it’s onto something beautiful. With this child, we will think about more ways to engage him around this inverse relationship, opportunities for him to justify his thinking with a visual diagram, and also make conjectures. (If

iis equivalent to

, what other problems will follow a similar structure?

Story #7:

I have 104 candies and I want to split them with 7 friends and I want some candy too. So I want to split them with 8 people.

This one just needs a question! I can see how this child is wrestling with a discussion facilitated by the classroom teacher, about how ‘sharing with 7 friends’ results in eight groups, not 7. I think this next child had a similar line of thinking:

Story #8:

Ian has 104 rocks. He has to give 8 rocks to his 7 friends. How many rocks can be given to each person?

I didn’t get a chance to check in with this child, but I wonder if the ‘8 rocks’ was a vestige of an early thought. Sometimes, as we are exploring student thinking, we are not detectives but archaeologists, digging through the debris of earlier thinking and attempts. What conceptions are relevant to our planning for future learning? Does this child understand why his question of “how many rocks can be given to each person” is inadvertently answered in the story?

Story #9 is similar.

Story #9:

I have 104 candies and I want to split them with 7 friends and I want some candy too. So I want to split them with 8 people.

I think the student may have been so focused on making certain they remembered that the 7 int he problem does not translate to using a 7 as the divisor, that they made some small errors. I’d need to talk with the students to know more.

Story #10:

Ava needs 104 juice boxes for a field trip. She bought 12 packs of 8. Is that enough? If not, how many more does she need?

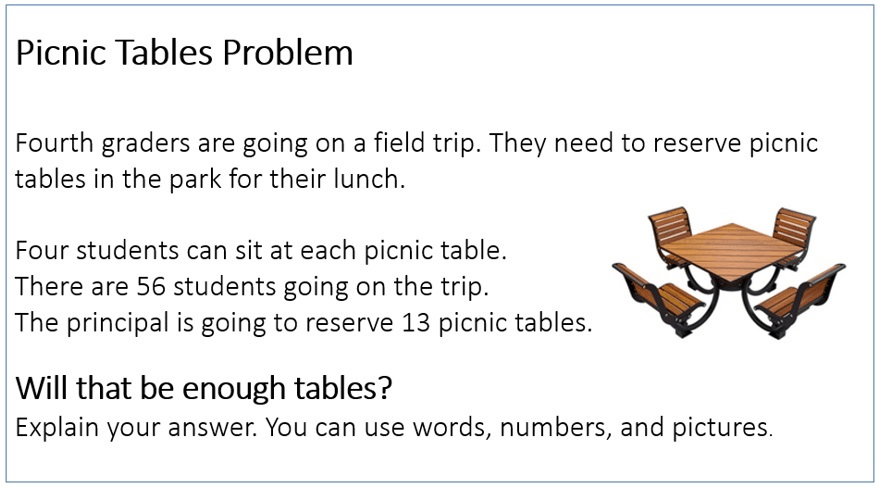

I love this problem! It technically doesn’t represent 104 ÷ 8, but it’s a great context. It reminds me of the picnic tables problem that we used earlier on in this unit. (You can read about this lesson in Marilyn Burns’ blog.)

This lesson happened almost two weeks ago. I wonder what helped it stay so sticky in her mind.

The Fine Line Between Creative Insubordination and Boring Ol’ Insubordination

Xander wrote this:

“Write a story? No, but I will solve the problem, because I can’t think of a story.”

I handed the paper back to him. “Xander.”

“Fiiiiiiine.”

Five minutes later, he submitted the following to me:

I was bored for 104 hours in math class. You need to divide it by 8.

Nope. This does not show any understandings about division. I attempted to hand it back to Xander, but his eyes went glassy. We ha a brief conference about why 104 ÷ 8 is not his suggested answer of 16, but it was clear that Xander was Not. In. The. Mood.

What do we do with this?

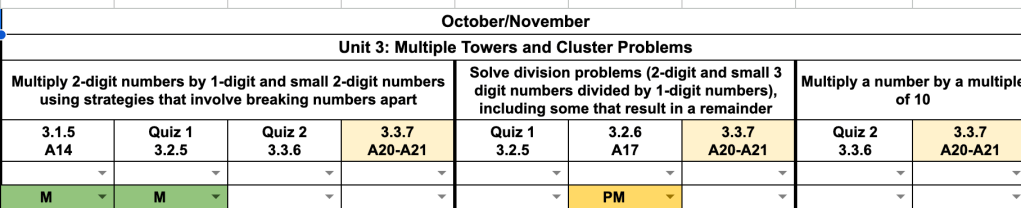

A few teachers have started using spreadsheets to help keep track of whether students are meeting, partially meeting, or not meeting different curricular benchmarks over the course of the unit.

As the classroom teacher and I started to fill it out, we started to take note of patterns of thinking for students. How were students solving these division problems? Did they decompose the dividend? Did they think about it as multiplication inverted, and decompose the factors?

There were a few students that we noticed who did not demonstrate a clear understanding of division as sharing amongst a set number (partitive) or creating equal size groups (quotative), and often they struggled with the computation, as well. The classroom teacher and I will meet to discuss opportunities to reinforce these ideas for these kids, and I’ll work with them during a block tomorrow.

Ultimately, it was helpful for us to determine that “success criteria,” that we were looking for an understanding of division. Perhaps this speaks to who I was as a child, but there is a playfulness and a creativity to getting to write about nivelsnorts and flying tomatoes, and I don’t see a need to deny students that. And, ultimately, this activity was about assessing student thinking. I needed to look for signs that the students undrerstood rather than writing them off as kids who don’t want to follow the game of school.

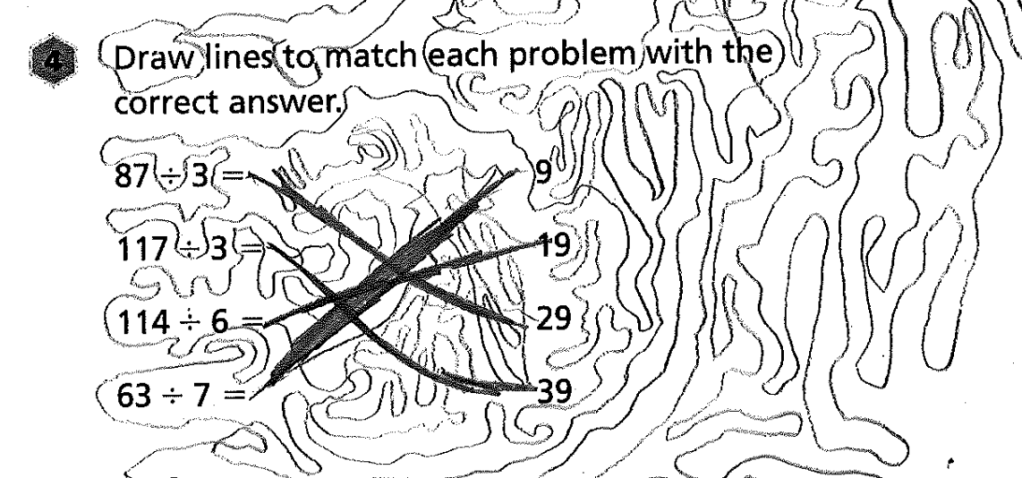

Ultimately, we all have our boundaries that students want to push. One fourth grader handed me this, and I told him that I wouldn’t be able to figure out what answer he had selected. If the whole point is to undrestand more about his thinking, and instead i spend all of my time tracing these spaghetti noodle lines, we have failed each other.

You will notice that he added much thicker lines later, to indicate his thinking.

This isn’t to say that you, personally, need to accept student work that talks about nivelsnorts and flying tomatoes. This is to say that, when we focus on what math we see, and what math we want to see, we may allow some additional student agency to creep in, and that’s fine with me.

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I love these! I think my favorite is the flying tomatoes. But I’m also burning to know whether the trick question in Story #1 was intentional or just an oversight.

When I think back on doing schoolwork as a kid, I remember the satisfaction of finding a creative way to turn a boring assignment into something more interesting. It’s nice when the prompt is open-ended enough that the creativity can be channeled in a way that is more productive than spaghetti lines 🙂

LikeLike