When we look at student work after school, long after the students have left the building, we make inferences — guesses — at what students were thinking. We ascribe meaning and importance. We take into account everything we know about math content, and mathematical learning progressions, and how students typically solve the problem — and how this student typically engages with math. We read student work like texts, and bring in all of our background knowledge.

And, because we are human, our background knowledge is infused with bias, both in favor and against different students and their identities. We can’t help it. But does that mean we should remove context? What can we learn from student work that is stripped of as much context as possible?

I’m going to start by showing you some work, and filling in my own background knowledge.

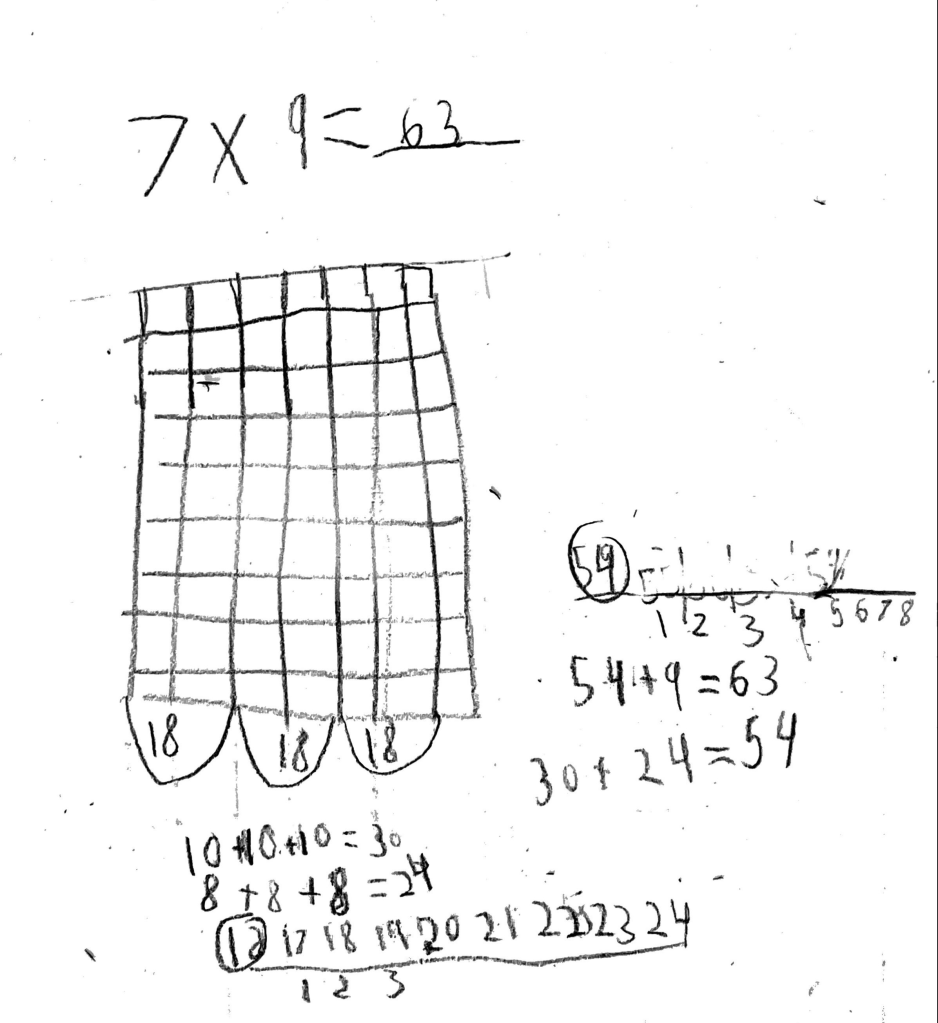

Hazel’s Work on 7 x 9

Earlier this week in third grade, students were asked to choose a multiplication problem within 100, draw an array, and show how they determined the product. They just finished their first ever unit on multiplication and division. I peered over students’ shoulders to see their work. I expected to see lots of counting strategies, since most students are not fluent with multiplication facts at this point. One student chose 1 x 1, a clever way to get dismissed for snack a few minutes earlier than his classmates. Other students chose things like 2 x 8. Simple to draw, simple to solve.

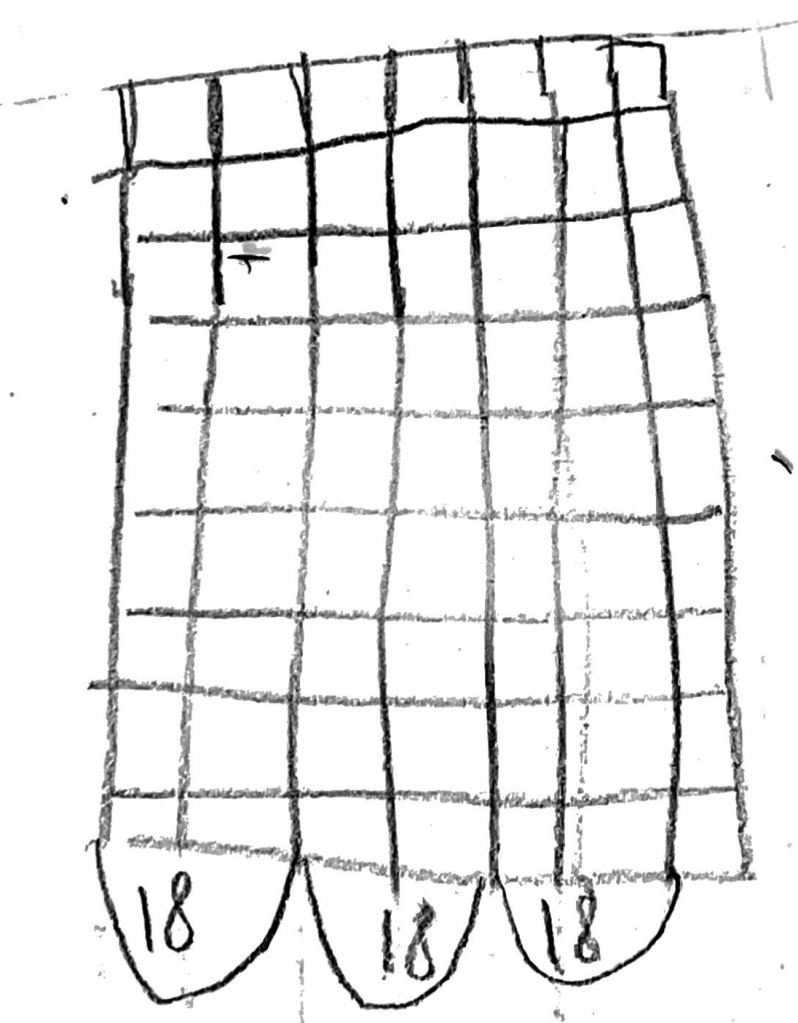

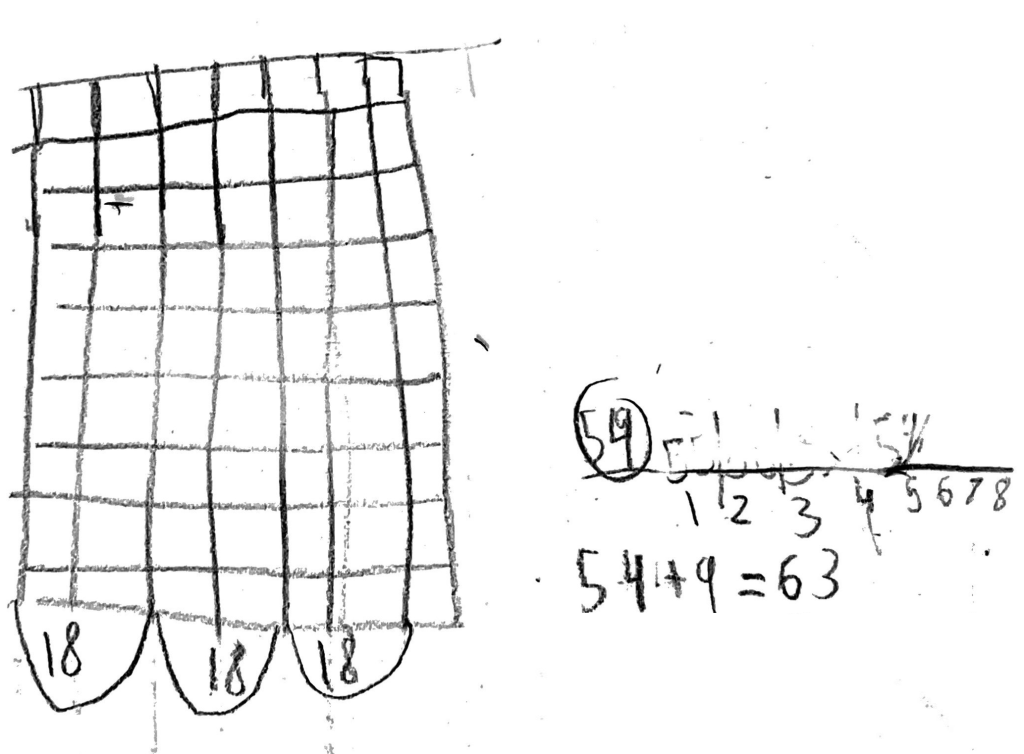

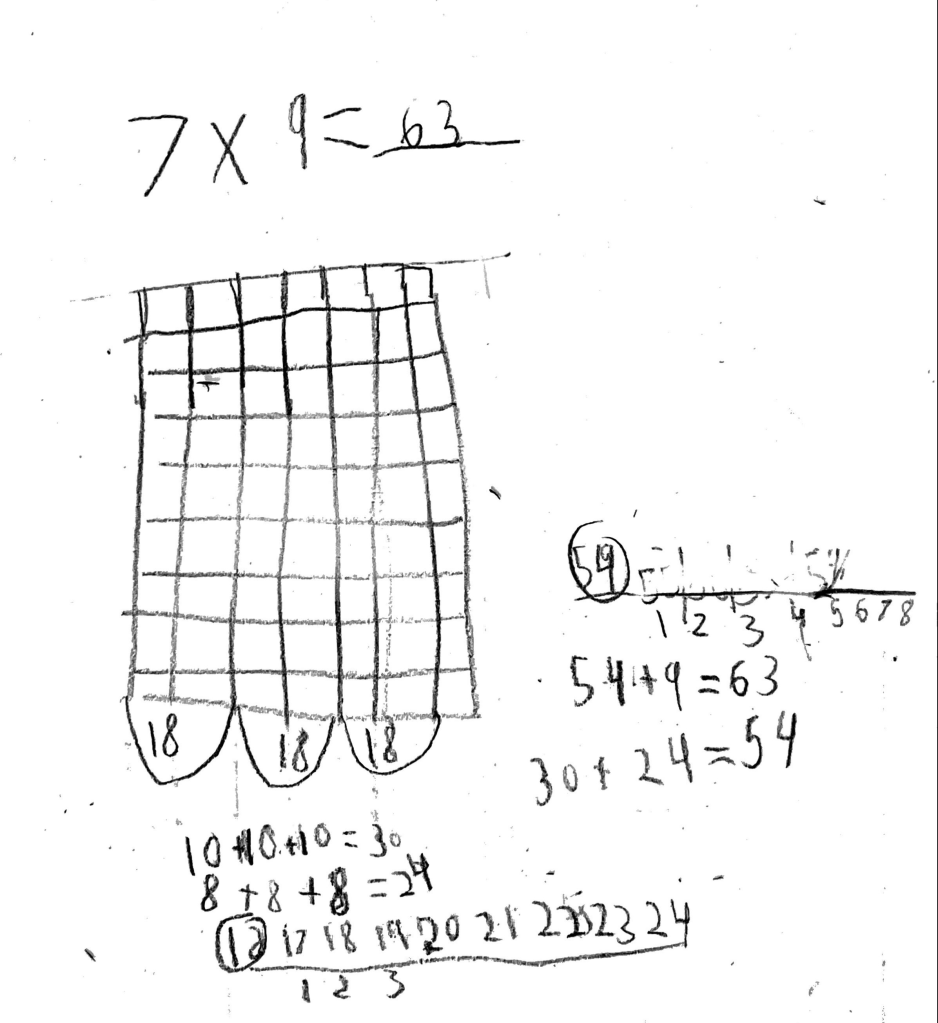

Hazel* chose 7 x 9. Bold! Here is what her work looked like:

Did my jaw drop? I think my jaw dropped. Hazel’s work was thrilling!

My Context

And I realized that some of my reaction to Hazel’s work is because I contextualized it with background knowledge about her. I met Hazel when she was in kindergarten. It took her a little longer than her classmates to demonstrate one-to-one correspondence. It took her a little longer to get those teen numbers down. Everything took a little longer, and by the end of kindergarten, the special education team evaluated her. She now has an IEP, with a math goal.

Hazel is in third grade now. I did not see her much in second grade, so it feels like I have a gap in my understanding of her mathematical learning. Many of my memories of Hazel are of her sprawled out on the rug as she wrestled with a counting collection. I remember nudging her towards different organizational tools, like cups or ten frames.

Still, Hazel is just as engaged and curious as she was in Kindergarten. She readily shares her thinking, even in rough draft form. While she can be impulsive, she also thinks deeply. She expresses that she doesn’t like math, but, time and time again, she reveals some impressive thinking about mathematical concepts. This work was thrilling but not surprising. I have seen her make brilliant connections in the past.

And I wonder how much of my excitement came from knowing that her disability has impacted her mathematical performance in the past.

Learning More: Talking to Hazel

When we look at student work on its own — just the paper and pencil trail of mathematical ideas — we are detectives. We piece together what we think happened.

In this moment, though, I had Hazel in front of me, so I asked her to explain how she solved it.

“I drew an array that is 7 times 9,” Hazel explained. “But I don’t know 7 times 9. But I know two 9s is 18.” She pointed to the bottom of her array, where she looped groups of 18.

“So that’s 18 + 18 + 18. But, um, I don’t know 18 + 18 + 18…”

“That’s okay,” I told her. “That’s not a fact I have memorized, either. So how did you do it?”

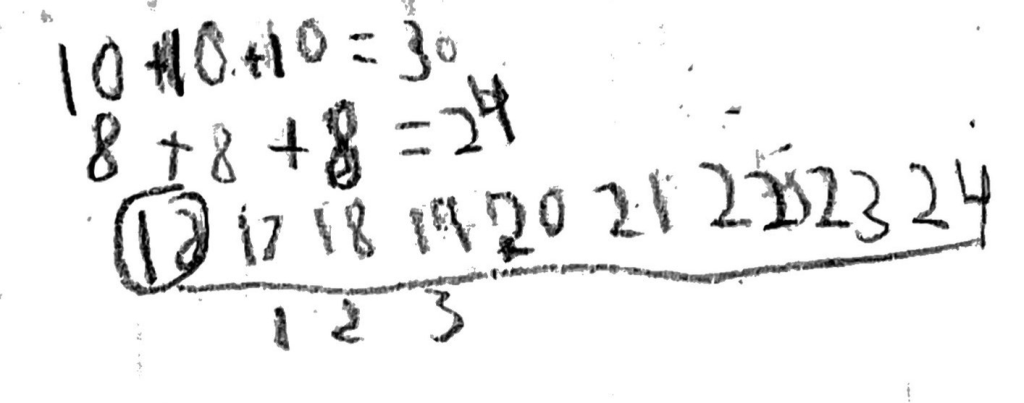

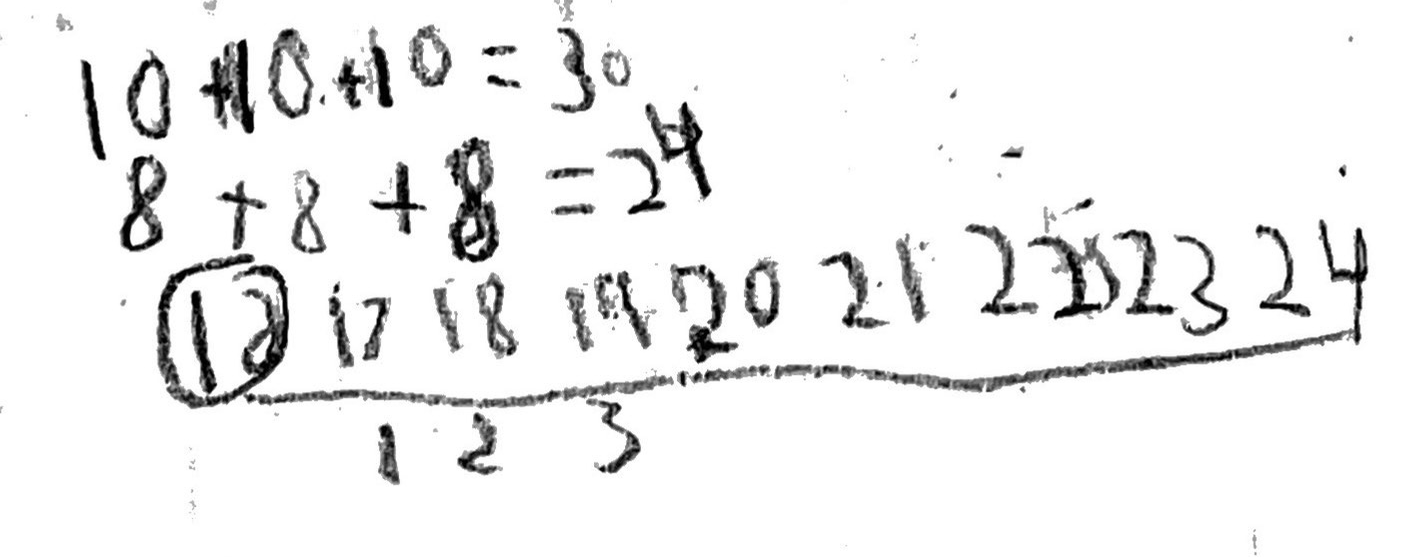

“I made it 10 and 8. 10 + 10 + 10 = 30, and 8 + 8 + 8 = 24.”

“It looks like you knew two 8s is 16, and then counted on to add the third 8.”

Hazel looked a little embarrassed — lips pursed, eyes down — but I praised her: “Hazel, that’s great! It looks like you have a number line strategy to make certain you’re keeping track of how many you’ve added on. It might take a little longer, but it shows how careful you’re being.”

She looked up, and I think I saw her her lips curled into the slightest of smiles. It can’t be easy to feel slower than the other kids, especially when the boy next to her was the one who had whipped through 1×1.

“What next, Hazel?”

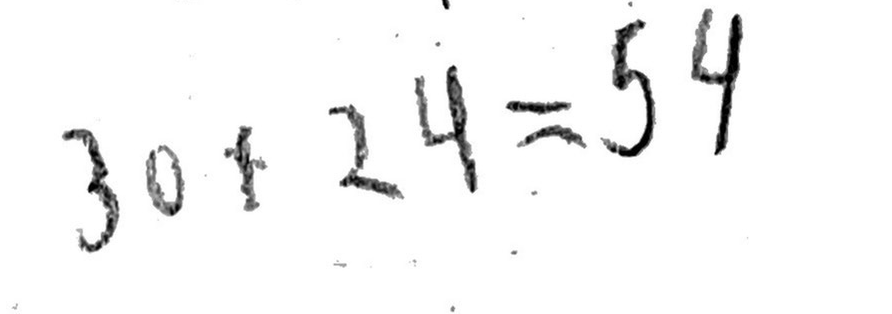

“30 + 24 = 54.”

“And that 30 is from the three 10s, and the 24 is the three 8s?”

“Yeah, so now I have three 18s.”

“Brilliant!”

“But that wasn’t enough.”

Hazel has great dramatic timing. She pointed to the final column of 9 in her original array, still unlabeled.

“So I need to add another 9.”

To be transparent, she hadn’t added the 9 yet when I first asked her these questions. I watched her set up a number line without prompting, and begin to count on from 54. She labeled each number below it. “But my paper can’t fit all the way to 9, and I need to add 9,” Hazel lamented. She started to erase her work.

“No, no, don’t erase it! I love what you’re doing!” I feel like I plead with one kid not to erase their work every single math block. I love those little remnants of thinking. It’s fuel for the mathematical detective, hoping to understand what happened.

I watched Hazel use her finger to tap out each number, counting on from 54: 55, 56, 57, 58… She paused when she got to 62, which was 8 larger than 44, and then tapped the table next to her paper. “Is it 63?”

“Does 63 make sense?”

Kids visibly bristle when I ask that question. I should probably come up with a new way to ask whether they think their work is reasonable. (They also hate “what do you think?” Maybe it’s less the phrasing and more that, after a lot of work, they really want me to validate them in a specific way. They want to hear that they’re right.)

“Yeah…”

“So what was your original problem?”

I watched Hazel’s eyes scan the paper, until she confidently said, “7 x 9.”

“So 7 times 9 is…?”

“63.”

Brilliant In and Out of Context

Hazel’s work showed that she understands how to decompose a factor using a visual representation of an array. She has strategies for doubling that involve decomposing multi-digit numbers based on place value, and she is able to count on when she does not know a given sum.

She did not demonstrate much multiplicative thinking, where she found equal groups, although this work demonstrates a comfort with the representation of an array. That said, she didn’t count the columns of nine — she connected the nine to her chosen problem of 7 x 9, and built from there. This shows some early understandings of multiplication as involving groups (or rows and columns). We will have to figure out ways to support her as she moves beyond doubling.

…and what’s next?

It’s easy to get so excited about student work that we settle. It’s good enough!

One of my favorite things to witness in third grade is the transition from additive to multiplicative thinking. While Hazel worked hard on this problem to determine the product, what opportunities do I see to push her towards her multiplicative ideas? This feels brilliant for early on in third grade — Hazel is right on track. And I think I’d still find a lot to love about this work if it came from a seventh grade student, but also… it’s nice that the next steps for Hazel are exactly what we’re going to work on in her class. (See: “Yes! And!”)

The day that Hazel produced this work, I happened to be meeting with the wonderful Joanna Hayman — a tireless advocate for math education for all students. I’ve seen Joanna present about inclusive math spaces, neurodivergent learners, and student sense-making. (For my CA friends, she will be presenting at CMC — North, South, and Central — and she’s not to be missed.) “Am I just excited about Hazel’s work because she’s got a disability that impacts her math performance? Or…?”

I can’t remember exactly what Joanna said, but she pointed out that I seemed really fascinated by what Hazel did. It’s creative, and conceptual, and accurate. Maybe my enthusiasm has some additional shades of color because of the context, but it’s just interesting thinking to me.

Today, while I was in Hazel’s third grade class, I emphasized to students that we are formalizing how we record multiplication and division with symbolic notation. Let’s write 4 x 7 = 28. Maybe you solved it by doing 7 + 7 + 7 + 7 — write that, too! — but we want to start to build up multiplication connections in our brain. This was a message that I was happily giving everyone, and one that is explicit in our Investigations curriculum, but I’ll be honest: I was also thinking about Hazel. It can be helpful to have a student in mind. We don’t want bias to lower standards for students. Maybe context can help us elevate.

*This is a reminder that I always give students a pseudonym, and remove or change identifying information, for their privacy.

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I love this! Thanks for sharing. Yes to elevate!!

LikeLiked by 1 person

This makes me think about the idea of “conception” vs. “misconception” that I recently read about in an email newsletter. Unfortunately, I can’t remember who it came from but it was in a quote from Dr. Rochelle Gutierrez. Instead of fixating on kids misconceptions, let’s look at their conceptions so that we can help them learn more and better. Thank you for this post! BTW, I loved your presentation at NCTM in Chicago.

LikeLike

Elisa! You were there?! How did this not register with me! Next time, let’s chat for real. 💛

And YES, I love that work from Dr. Gutierrez — the focus on the genuine ideas, so that we can leverage it for more learning. It’s beautiful. I struggle sometimes with what is a genuine conception — with conviction, and sense-making — and what might be something the student threw out there. (Goodness knows there’s times I look at my late night e-mails, and marvel at them with that same ‘oh my goodness, where is this thinking come from’ wonder.) But yes! Let’s focus on honoring student thinking rather than writing it off quickly.

LikeLike

Agreed! I’ve been trying to really focus on what students know and find that I sometimes slip into deficit thinking. I have to really watch myself. It’s so easy to forget to focus on strengths when confronted with an overwhelming, developmentally inappropriate curriculum. Important to stay focused on what students demonstrate they know in order to teach them what they need to learn next.

LikeLike