Today, the first graders revisited “Peas and Carrots.” They had spent several days exploring part-part-whole thinking in the context of games like “how many are hiding?” and “counters in a cup.” The classroom teacher and I wondered what new thinking students might have.

Instead of working with 7 vegetables on the plate, students would now be working with 9. Classroom teacher Rachel launched the problem again, and set students off to work — independently this time. We were thinking about student agency. Where do students make choices as they are solving the problem? How do they exhibit ownership over these choices? How do these choices contribute to students building positive mathematical identities?

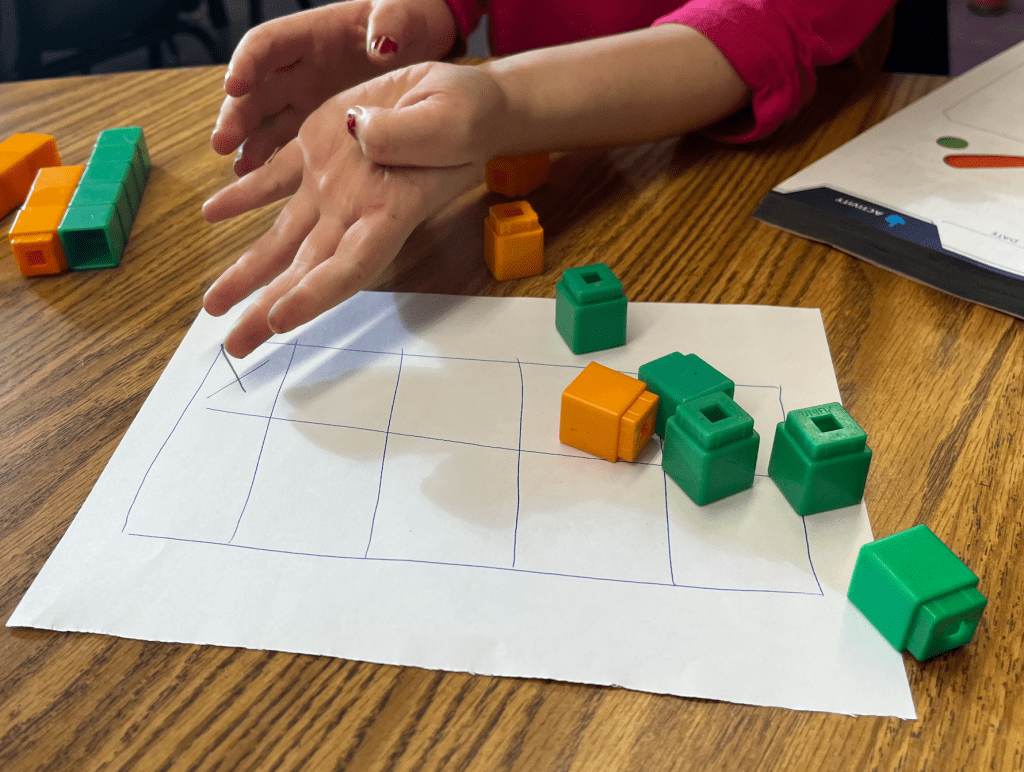

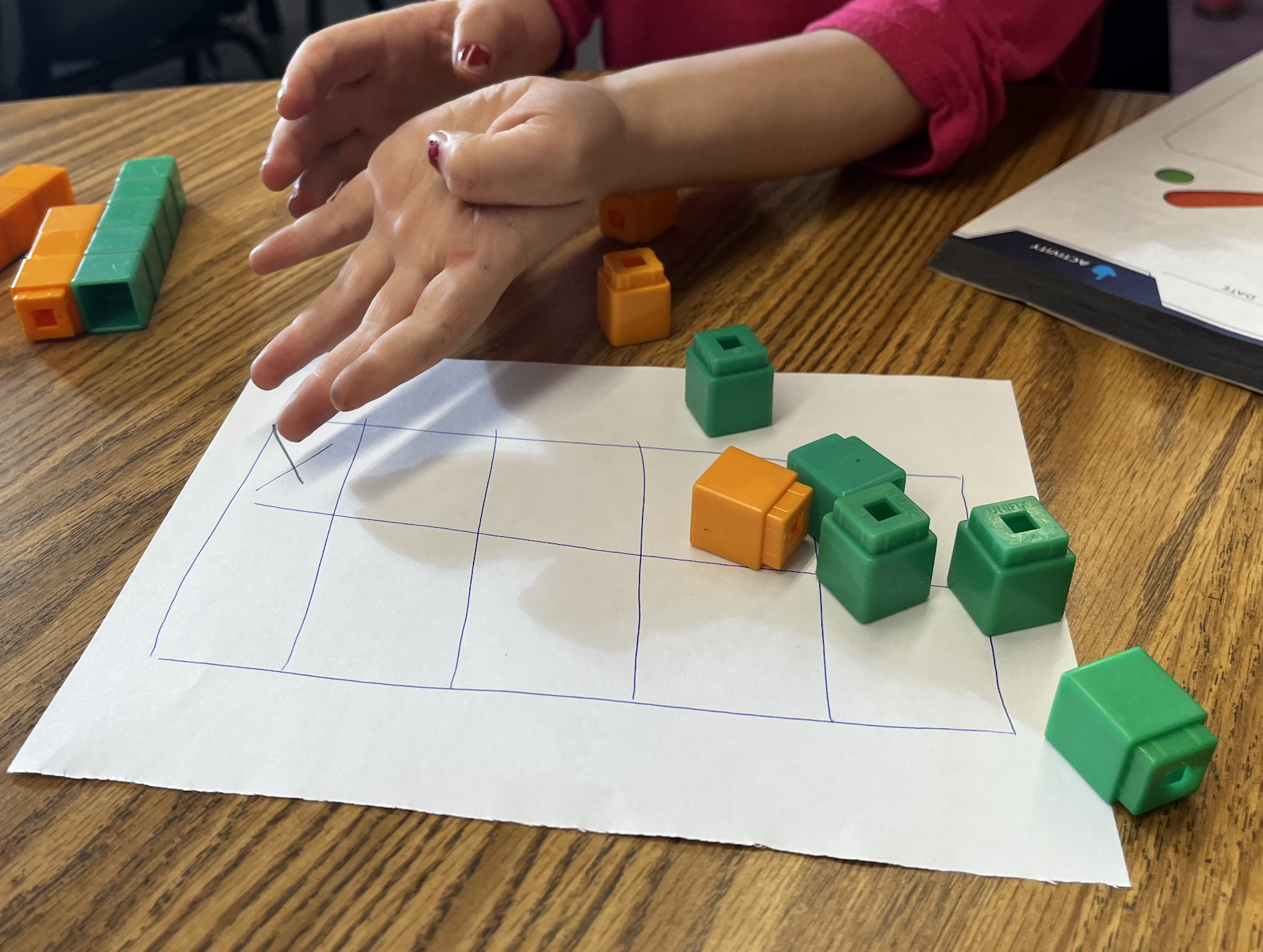

Charlotte and Gracie ended up sitting beside one another, so I joined them. They brought with them their student workbooks, and sticks of 10 green and orange cubes to represent peas and carrots.

Gracie understood the context instantly this time. (There’s no eating; there’s just ‘had.’) She had to adjust to the change in number, however.

After concentrating intensely on a name tag on the desk, Gracie pulled 5 green cubes (peas) and 3 orange cubes (carrots).

“How do you know that’s 9?” I asked.

I expected Gracie to use a ‘count all’ strategy, counting each cube from one. That’s her go-to strategy. She is more reliably successful with counting all. This isn’t unusual in first grade, but we’re trying to nudge her towards counting on and back in this unit.

Gracie scrunched her nose, and pointed to the name tag. “Look. I took 5,” she started, gesturing to the green cubes. “And then I needed 3 more.”

The name tag had a number line on it. There were 3 numbers between 5 and 9.

“So that’s 9? Are we sure?” I asked again. I felt like my questions were leading, so I started to draw a ten frame on a nearby piece of scrap paper.

As soon as I had finished drawing the ten frame, Gracie took it and drew an X in the last square. “We don’t need this!”

“What?! How do you know?!” I was thrilled and I imagine it showed.

Gracie held out her hands. “When I have 9 fingers, I don’t need this one. So I don’t need that last square in the ten frame if I only want 9.” Brilliant. She was making mathematical connections like a pro!

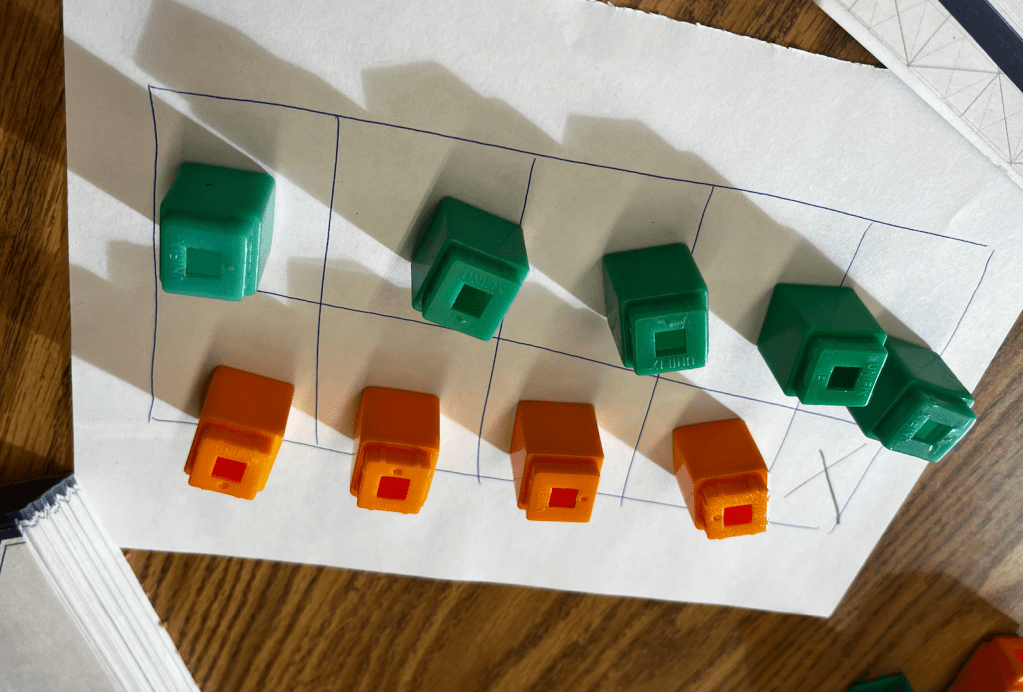

She began to fill the ten frame with her cubes, starting with the 5 green ones. She then placed the three orange ones, and, before she had finished the task, she noticed that she wouldn’t have enough.

“Uh oh! I need 4 carrots! 5 + 4 = 9,” she said assertively.

She recorded this combination in her book, and then set out to make another one. I watched her remove one green cube and replace it with an orange one. “There! Another way!” She was starting to think more systematically. “That’s… 1, 2, 3, 4… and 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. Oh! That’s the same thing but opposite!”

I was struck by how fluently Gracie moved between representations, from the number line to the ten frame, and how she used each one differently.

When do we introduce a representation to a student at work? How does that change the student’s thinking? How does this factor into student agency?

Gracie did not independently choose the ten frame, but once I drew it, she had total ownership over it. She manipulated the ten frame to fit the situation. She used it to organize her thinking, not to represent mine. In fact, as soon as I drew it, Gracie was done with me. (It was just as well. I was running late for 7th grade.)

Gracie seems to be thinking hard about how she can reason about quantities without counting everything all of the time. In the past, I’ve heard her express that this makes her “tired.” It can be tedious, and taxing on her working memory. I think she liked that the modified ten frame allowed her to keep track of quantities with greater ease.

I didn’t get to see the end of the lesson. (The 7th graders were waiting!) As I walked to the middle school wing, I found myself lost in thought about Gracie owning that ten frame. Here, I had been worried that introducing a representation would take away from Gracie’s agency and developing sense of identity as a mathematician. Instead, it served as a point of leverage. What conditions caused this to be a productive move? Can we predict when it would be counterproductive?

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

1 Comment