If you’ve never played Johnny Upgrade before, you should know that it begins with music. Epic music. Like anthemic, sweeping, about to vanquish the villain at the 11th hour music.

The anticipation builds as you are plunged into Johnny’s World: an 8bit landscape littered with gold coins and the promise of adventure.

Then you are given 2 seconds. For the duration of those two seconds, Johnny is completely immobile, no matter how many keys you bang. (SsoIFJ3$sdfliAFj!) A question mark appears above his head, and then: “uh!” Johnny dies.

That’s when it starts getting good.

Before asking students to play Johnny Upgrade, I tell them that we are going to play a video game that might seem, well, unrelated to math. There will be a gun — even though I do not like guns — but that they will never aim it at a person. They will know that they’ve won when they’ve defeated the Big Boss. I teach them how to turn off the epic music and sound effects, so that they can talk with one another in breakout rooms. Then I announce — smugly — that I will not be telling them how to do anything else with the game.

It’s worth playing for yourself to figure out how it works.

. . .

I revealed the guiding questions to students right before putting them into breakout rooms: “As you are playing, I want you to consider: what does it feel like to collaborate? What does it feel like to persist? And what could this game possibly have to do with math class?” A few kids chuckled.

“If you’re feeling stuck, feel free to talk to people in your breakout room. Unmute yourself, or use the chat to write a message. You can always call me to your breakout room, too, but remember: I’m not going to tell you how to play the game.”

“It can’t be that hard! I’m a gamer!” Jonah in my 2nd period class announced.

. . .

Playing the game takes perseverance. After each frustrating loss, you are sent to a menu of skills to “upgrade.” At first, you only have enough money to upgrade the speed. The good news is that increasing Johnny’s speed breaks him free from his Round 1 paralysis. He is now able to move, at least enough to gain a few coins. Pretty soon, you’re able to choose between increasing speed and jump power. Which one will be the most advantageous?

As the game continues, you collect more coins, enough to upgrade your energy, or increase the time limit on the game, or even increase the value of a coin by 50% to be able to afford upgrades even quicker.

. . .

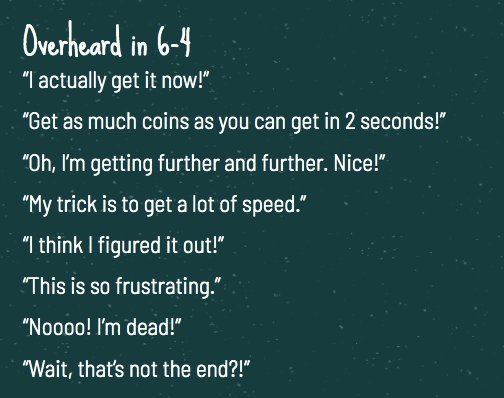

I bounced between breakout rooms as my sixth graders played the game. At the beginning, a few students seemed frustrated, but all of them stuck with it. A few minutes later, everyone was hooked. I transcribed things that I heard students saying, which included:

- I actually get it now!

- I can’t decide whether to make him go faster or jump higher.

- Wait… how do you do that?

- I think I’ve almost got it!

- Oh, I’m getting further and further. Nice!

- Hey, just so you know: technically jumping power is super important. (Response: Oh! Good to know.)

- I’m not sure how this works.

- Wait… that’s not the end?!

- You need to make smart investments.

I recorded what I heard on a slide to share at the end of our breakout sessions.

“Some of the things you said are things I’d love to hear in every math class!” I exclaimed. “But, um… not all of them.”

. . .

In all four of my 6th grade sections, students expressed real disappointment that they would not get to finish the game. (“I’m so close!” several of them protested, despite having no idea how far they were.)

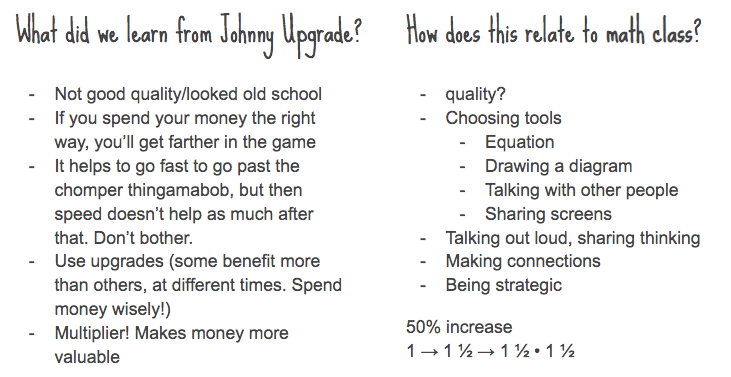

I asked students to share what they learned from Johnny Upgrade, followed by what it might have to do with math class.

The lessons they learned from Johnny Upgrade varied. One section focused intensely on specific strategies. (“It helps to go fast to go past the chomper thingamabob, but then speed doesn’t help as much after that, so don’t bother upgrading.”) Another section focused on the feeling of persistence, and what about the experience encouraged them to keep going. (Talkative breakout rooms sometimes helped, but not universally.) My third section focused on the experience of having obstacles, and my final section wanted to talk about the “multiplier” upgrade, since they seemed to think that was the most mathematically oriented part of the game. I transcribed everything on a slide for each class.

Then, we discussed what this might have to do with math class.

“It’s important to decide which upgrade to use when. That’s like when you have to decide what strategy to use in math class.”

“We talked out loud a lot. It helped to hear what other people were doing.”

“Yeah, even though we all did it individually, it was nice to talk.”

“I had to be patient. It’s okay to fail a few times first.”

“Every time I failed, I got a little bit further.”

. . .

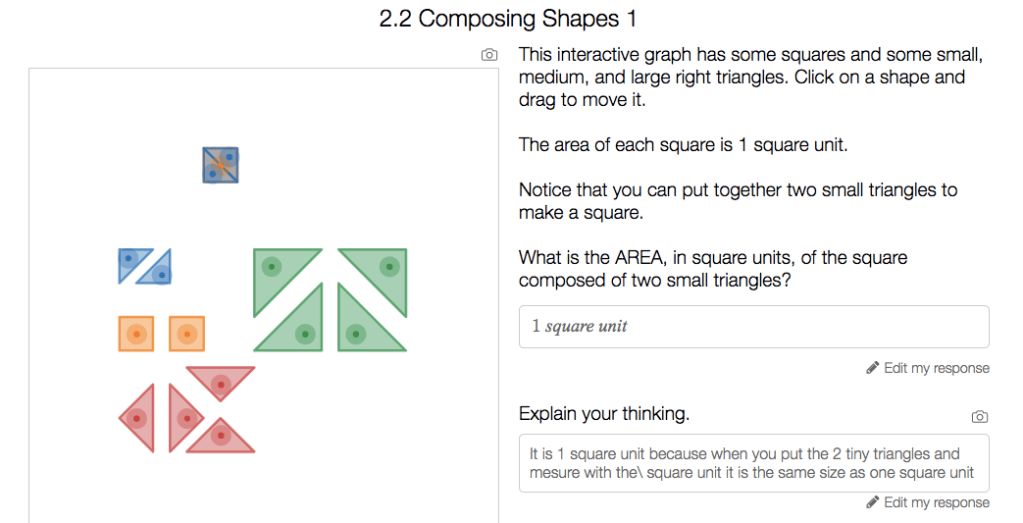

After our Johnny Upgrade debrief, we continued with our unit on area. I returned students to their breakout rooms, which had been infused with an extra spark after playing the game.

. . .

Class time is precious. In ‘remote learning,’ I feel especially committed to the idea that any minute I ask students to be on a screen must serve a purpose. (The purpose might be to build community rather than to develop strategies for calculating the area of a parallelogram, and that’s okay.)

The game allowed every kid to experience failure in a safe and individual-but-communal way. None of the sixth graders had played Johnny Upgrade before, so they all experienced that initial frustration with the first few rounds. Some made it further in the game than others, and that was okay. Some students felt comfortable talking in the breakout rooms, and some preferred to use the chat box.

Every single kid stuck with it. Every single kid felt that drive to keep going.

I understand that this won’t always happen in math class — that students may not feel that same drive to continue through perceived mathematical failure. When they want to quit, I can illuminate some of their strengths. I can listen to them vent frustration. I can pair them up with peers, if that feels safer.

I’m grateful we all have this anchor experience for persistence. The next day in class, I launched a math activity with the slide of things I had overheard in that section. “These are all sentences that belong in math class, too,” I reminded them.

“Even ‘I’m not sure how this works’?” a student in 6-3 asked.

“Absolutely! That may even happen today, as you try to figure out the area of some unfamiliar figures with unusual shapes. If that happens, we can talk about what you do know, and make connections to help you figure out what to do next.”

“Oh. So that game really did have to do with math class,” another kid added, sounding faux-disappointed. I think caught a flash of a grin, too.

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Brilliant lesson!

LikeLiked by 1 person

sucks that my school blocked this because this was the best game, yet im reading your article and drooling on the school computer

LikeLiked by 1 person