Mia* is a fourth grader who participates in a small-group intervention with me that focuses on multiplication. She is enthusiastic and playful — curling the dot in the i in her name into a heart, and narrating her thinking with droll asides like “I promise I have a better strategy… maybe.” She is also hardworking, and collaborates well with the other students in the group. Group membership was determined two months ago, after I interviewed many students across the grade using a protocol from Marilyn Burns’ Listening to Learn (Interview 6: Foundations of Multiplication). After two months, the students were re-interviewed using the same protocol.

In October, Mia correctly answered 10 out of 12 questions.

In December, Mia correctly answered 10 out of 12 questions. Again.

On the surface, it would seem like the group was a failure: two months later, and a student’s thinking hasn’t changed?

But that simple score — 10 out of 12 — doesn’t actually reveal whether the student’s thinking has changed. To assess learning and development, I need to look more closely at how Mia reasoned through the tasks, not just how many questions she answered correctly. This is what I love most about interview assessments.

The Beauty of Interviews

I have written about clinical interviews many times before; it’s one of my favorite forms of assessment. It is not the only thing that I do to assess student reasoning — and there are times when they are less practical — I have found that conducting interviews has been instrumental in deepening in my own understanding of how students think mathematically.

Earlier this month, Marilyn Burns gave a webinar on reasoning as the “essential foundation for building students’ understanding.” (As part of TERC’s “Forum on Equity in Elementary Mathematics” series, the recording is freely available.) My favorite thing about this session is its extensive use of video clips featuring students from across the elementary grades, offering examples of many ways that mathematical reasoning can look and sound. The emphasis is on how students think. Correct answers matter, but they aren’t sufficient if our goal is to understand the strategies and ideas that produce them.

How a student responds to a single question is rarely enough to draw conclusions about their mathematical thinking. A particular strategy may emerge because of the specific numbers involved, or a subtle feature of the wording, or the structure of the task itself — and that variability is important. We want students to be flexible in their approach. It is evidence of sense-making. And while there often isn’t one ‘best’ strategy, some strategies will be more efficient or sophisticated than others.

Mia’s October Interview: Additive Thinking

In October, Mia correctly answered 10 out of 12 questions during the interview.

Mia demonstrated a decent conceptual understanding of multiplication. For this visual, she correctly identified that the 12 in 4 x 3 = 12 represented the number of stars in all, while the 4 represented the number of groups and the 3 represented the number of stars in a single group.

However, to solve 7 x 6, she used an elaborate ritual of using fingers to count every single item. She counted out 6 fingers — 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 — and then hit a pinkie to signify that was one group. Then she used the same 6 fingers — 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 — and then hit her right pinkie and adjacent index finger to record two groups, and continued in that manner. She was able to get 42, but it was through sheer will, determination, and brute force. Ultimately, this is what qualified her to participate in my intervention group: while some students in the group were able to produce correct answers more reliably, all of them were stuck in additive thinking involving counting and fingers.

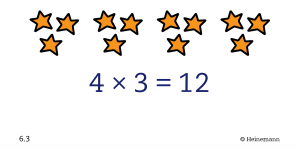

The final question in the interview is as follows:

“The answer to 20 x 8 is 160. Use that information to figure out the answer to 21 x 8.“

Mia looked at me inquisitively, then asked, “do we add a 1 or a 10?” I did my best to maintain a neutral expression, so as not to give betray whether she was correct. “I mean, it is in the 1s place…” she continued, referring to the adjustment from 20 to 21. She nodded bravely, as if motivating herself to go forward, and then said: “I think it’s 161.” To me, these responses showed that Mia understands that multiplication is about equal groups, and yet her only strategies for calculating multiplication problems were additive in nature.

Mia’s December Interview: Multiplicative Thinking

The December interview took less than half the time of the October interview. That, alone, suggests significant progress.

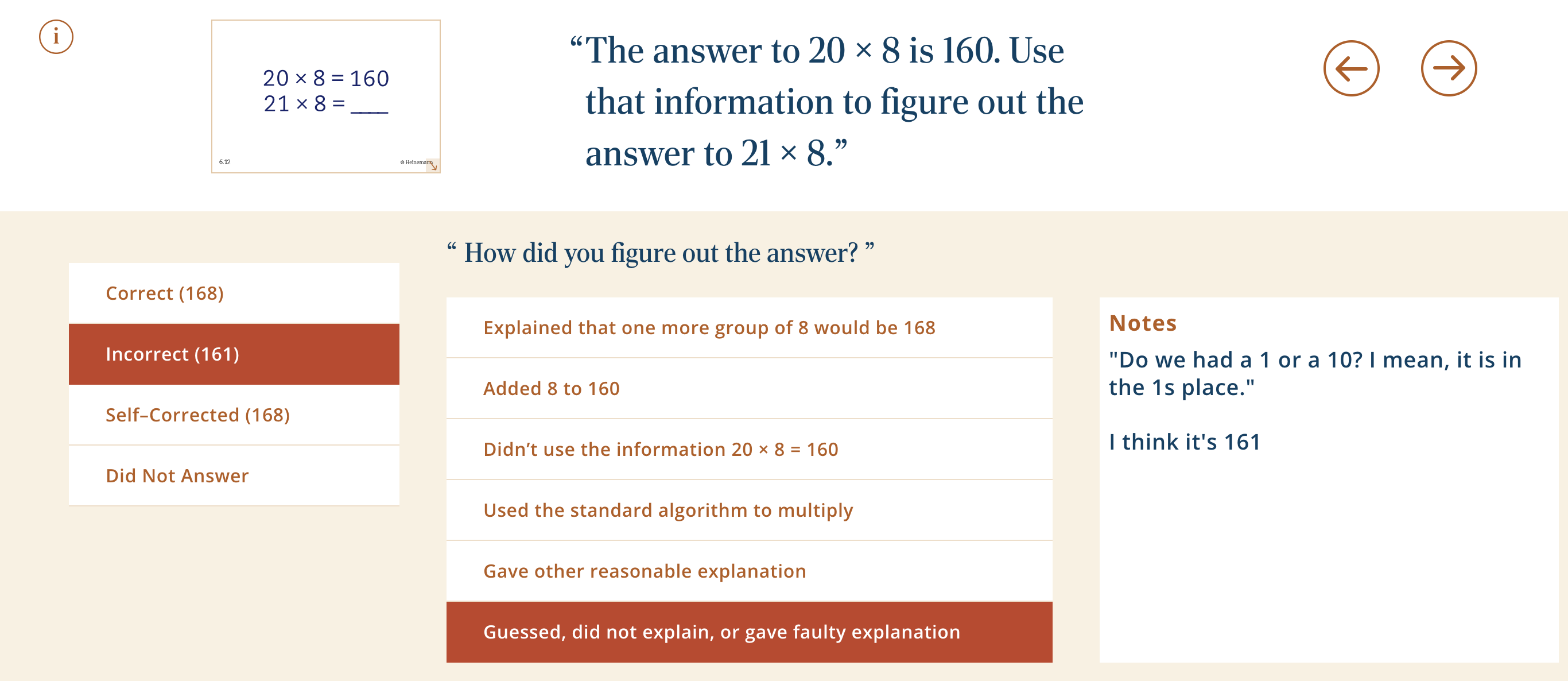

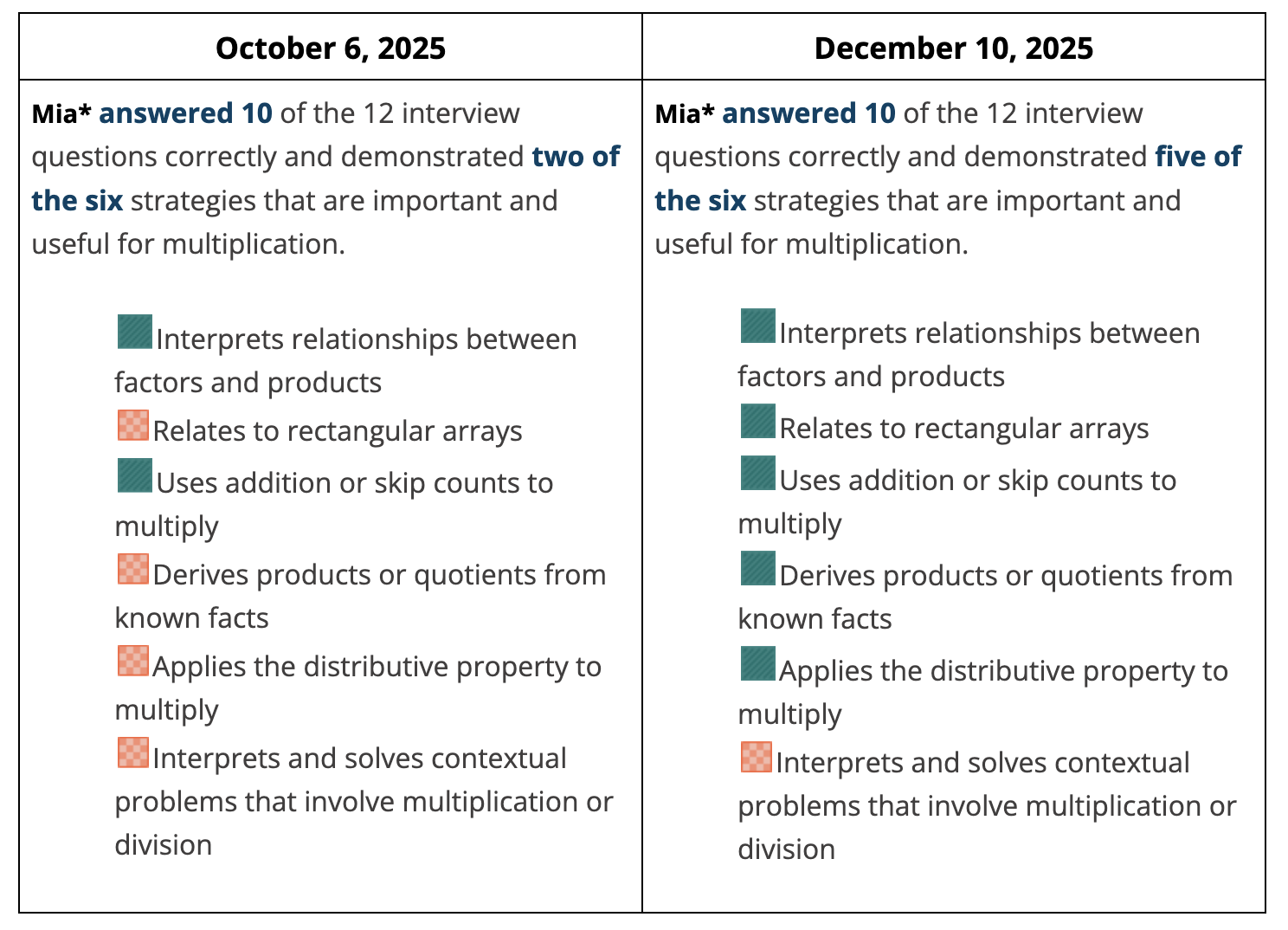

In December, Mia demonstrated that same strong foundation about what multiplication means, but with much stronger strategies that leaned into multiplicative thinking! I was able to use the same protocol again because, during the first interview, I did not share the correct answers with her. Here is the overview from her interview report:

Although she answered the same number of questions correctly, she was demonstrating more strategies! Previously, she had only demonstrated the first one: “interprets relationships between factors and products.” Now, she was showing a more robust understanding.

For example, to solve 6 x 5, Mia said that she “did 5 x 5, and plus another 5 is 30.”

For 7 x 6, Mia leveraged her work from a previous problem. “Oh, remember 4 x 6 is 24? So it’s 24 plus another…” She heard me typing, and, in a panic, said, “oh, no, don’t write that down.” (I wrote all of that down. Sorry, Mia.) She then skip-counted by 6s to go to 30, 36, and… 42. While she had previously answered this question correctly, this new response showed a lot of progress in her multiplicative reasoning! She was no longer trapped in her comfort strategy of using fingers and counting all.

This really showed through in her thinking about the last problem.

“The answer to 20 x 8 is 160. Use that information to figure out the answer to 21 x 8.“

In October, Mia had added a one for the 1s place. How, she effortlessly knew that it was another 8. “So it’s 168.” YES.

Putting the two results side by side reveals this progress, in color:

Mia was close to solving the other two problems accurately. The red square next to “interprets and solves contextual problems that involve multiplication or division” doesn’t feel representative of all the great multiplicative thinking that went into her work with those two problems, but also: ultimately, she isn’t there yet.

Beyond Answers

I confess: sometimes I find wrong answers more interesting than right ones. There can be so many ways to get something wrong! But that doesn’t mean that I privilege wrong answers, just that I’m happy to engage with them so that I can identify and leverage what the student does know.

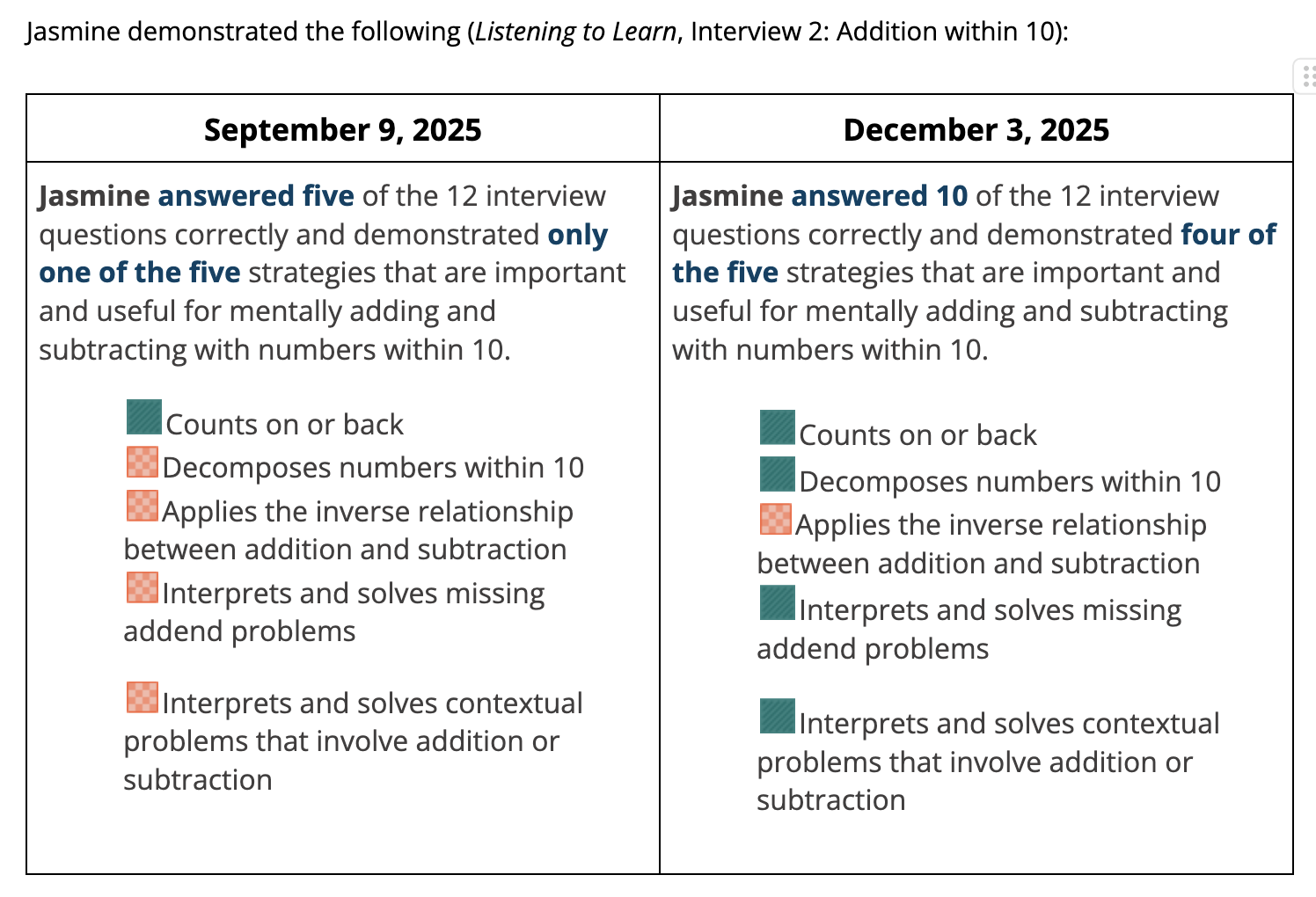

And, generally, progress does align with students getting more answers correct! Here is the comparison overview for a third grade student that participates in another intervention group with me, focused on addition and subtraction within 20. Jasmine’s strategy work improved and she went from answering five questions correctly to answering ten questions! Unambiguous progress!

Correct answers matter, but they are only part of the story. If our goal is to support students in developing robust mathematical reasoning, we have to look beneath the answer to the thinking that produced it. When a middle school student is still counting all to solve a problem involving equivalent ratios or doubling, the issue is not effort or accuracy: it is that their way of thinking has not yet connected to the structure of mathematics. That kind of thinking will eventually hold them back.

This is what I saw with Mia. Early on, her only way into the problem of moving from 20 × 8 = 160 to 21 × 8 was through counting and addition, so she added one instead of one group of eight. After developing stronger multiplicative reasoning, the same problem became obvious to her. In October, she had accurately answered problems that she could solve without thinking about multiplicative structure. but that fell apart for this task based on relationships. In December, her stronger multiplicative thinking was evident not just in her responses to problems like 7 x 6, but also here, where she was newly accurate. And that shift is exactly what interview-based assessment helps make visible.

This is why I return again and again to interviews: they help me see growth that scores alone cannot capture, and guide me towards the thinking students are ready to build next.

*As a standard disclaimer, all students are referred to by pseudonyms.

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.