How do elements of the culture students bring into the classroom interact with the classroom culture we create? What does it mean to shift or honor them?

Earlier this week, I watched the first session in TERC’s Forum for Equity in Elementary Mathematics series ’25-’26. Dr. Pam Seda spoke about “Culturally Relevant Math Tasks: When What You Teach Connects to Who They Are.”

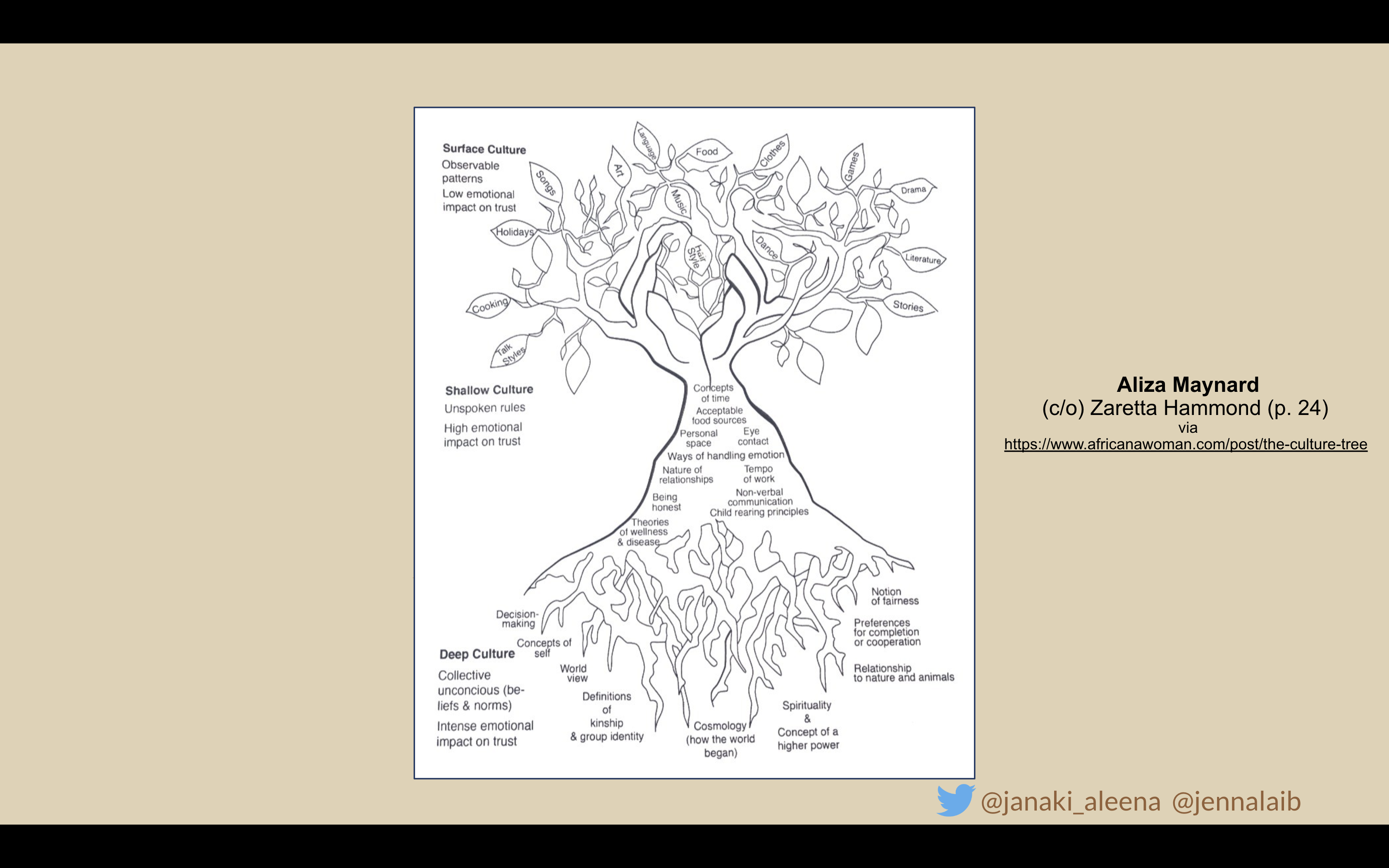

During the presentation, she used the visual of a culture iceberg, which I have previously seen modeled as a tree (via Zaretta Hammond). Dr. Seda suggested that it is not that we need to make every task feel exotic and diverse, but that we want to create relevant contexts while also being mindful of who is being centered. For any given task, there will be some students for whom that is a mirror of their culture, and some students for whom it is a window into another. We do not want students to never experience or only experience mirrors.

Dr. Seda’s talk resurfaced questions for me that I worked through with Janaki Nagarajan. Janaki and I gave sessions about culture in math tasks at NCTM and CGI a few years ago. We considered the idea that students bring culture into the classroom, and we also create a culture within the classroom. How often do these two cultures align — and what happens when they don’t?

Janaki and I shared the culture tree from Zaretta Hammond’s Culturally Responsive Teaching & the Brain (2014).

Surface culture includes observable patterns. Examples include art, food, clothes, songs, stories, and cooking.

Shallow culture includes unspoken rules. Examples include concepts of time, personal space, tempo of work, and ways of handling emotion.

Deep culture is the collective unconscious, comprised of beliefs and norms. Examples include notion of fairness, concepts of self, spirituality, and definitions of group identity.

Janaki and I met several times to plan our sessions, discussing elements of these categories of culture. Janaki’s parents come from different countries and cultures, so she was accustomed to moving between ‘worlds.’ I shared that I never realized just how American I am until the first time I went to visit my husband’s family in Algeria. It wasn’t just about food preferences, or my music. There were deeper elements about human interaction. It was how I wasn’t used to the intense stares of strangers in public. I wasn’t accustomed to such generous hospitality — truly exceptional — and also how questions that Americans view as personal were seen as anything but. (“When are you having kids? Soon?”)

Changing Elements of Culture

Again, we considered the culture brought into and the culture created within a classroom. Does classroom culture need to follow the dominant culture of a region? What if the teacher and the students come from different cultural or ethnic backgrounds?

As we examine the culture tree, we thought about changing different elements. We devised the following:

Changing elements of surface culture can make space for non-dominant cultures, and decenter dominant cultures.

Changing elements of shallow culture can challenge dominant culture.

Changing elements of deep culture can deconstruct dominant culture.

Janaki Nagarajan & Jenna Laib

I feel like my thoughts are still forming about this. Writing is my way of exploring an idea. When does it make sense to change elements? When does it not? Here are three instances of changing cultural elements — one from surface culture, one from shallow culture, and one from deep culture — that explore the idea. I’m not saying that these were the perfect changes to make. I’m saying that it’s interesting to think about how these interact with student experiences, as we continue to make complex choices within our professional practice.

Surface Culture: Marco and the Brownies

Fourth grade Marco had been in our district a few months, having recently moved from Italy. We launched a fourth grade unit about fractions with the following problem:

Imagine that there are seven brownies to share equally among four people. About how many brownies do you think each person will get? Do you think each person will get one brownie? Two brownies? More than two brownies?

The teacher distributed the sheet to each student.

Marco looked as if he were drifting off into space. I decided to anchor him by acknowledging what he does know about this problem.

“What are you thinking about?” I asked him.

“I am thinking… what is a brownie?” Marco’s eyes pleaded with me.

Of course! How could I have forgotten that not every kid in the class might be familiar with brownies? The problem might as well have been about sharing 7 zip-a-dee-doos.

I recognized that, in order to be successful with this problem, Marco needed to know:

- A brownie is a rectangular dessert.

- Brownies can be easily and effectively cut.

- Someone might want more than one brownie.

I pulled up a google image search for “brownies” on my laptop.

“Delicious!” Marco exclaimed. At this point, even without having tasted one, he would have a general sense of what to do.

“Do you like any desserts that look like this?”

Marco paused, lips pursed, until he was ready to offer: “tiramisu?”

I suggested that we think about the brownies as tiramisu instead, since it fit all the necessary elements: rectangular, can be sliced, and you will absolutely want more.

For me, this wasn’t about feeling clever. I wanted to make the task accessible. Contexts are powerful, and students need to be able to understand them in order to engage with the mathematics of the problem. Giving him access through the images and discussion of brownies helped him determine an entry point into the task. Switching it to tiramisu was a way to honor his Italian identity, and to welcome him into the ideas. In this moment, it felt natural. It may not always.

Shallow Culture: The Rug

I remember drumming my fingers nervously on a table as I waited for my internship interview. Every second felt like ten, easily.

Finally, the teacher came to get me. Her name was Ilana, and she had positioned her curly hair in a ponytail high on her head, curls spilling out like a waterfall. Ilana shared a few things about her practice before launching into a series of questions for me. She was previously a bilingual teacher. She spoke Spanish fluently. She loved teaching writing.

“Oh, and I’m a rug teacher,” I remember her announcing. I must have looked confused, because she followed that up with: “you’ll see.”

All of the instruction in Ilana’s fourth grade happened on a small rug area towards the front of the room. She called students there for a reading mini-lesson, and to launch math, and to hold a class meeting. It was a physical reminder that we were a community: everything that happened together happened right there. Students would then transition into independent time at their desk, or work in pairs around the room.

The rug area was purposeful and also quite crowded. Students sat close together, a school of children more closely resembling a school of fish. All eyes faced the board, or at least that was the intent. Some students asked for accommodations — a chair to sit on, some personal space away — but, for the most part, it seemed to work. Anecdotally, I felt like it gave us a greater sense of community, while also improving sight lines to the chalkboard. (Yes, I had a chalkboard.) There were times when we spaced out more, so that students could see one another’s face, but usually I wanted them facing forward. (Until writing this, I hadn’t considered the messages this sends about authority in the classroom.)

I don’t think students would have named this as going against their dominant culture, but, in their suburb of Boston, it was more common for people to have vast personal space: kids had their own rooms, families drove their own cars. Here, Ilana was deliberately pushing back on this norm in a way that challenged dominant culture, but didn’t feel inappropriate. Students grew accustomed to it quickly, and also learned how to sit near friends without letting grubby fourth grade fingers encroach on their personal bubble. This was part of the design of the classroom. Many of the teachers I had when I was a child were also rug teachers, and, when I was hired to teach my own fourth grade classroom the following year, I continued.

I work with plenty of “rug” teachers, and plenty of teachers that are not. I can’t say that one is better than the other. I can say that students get used to whatever structures are in place — and that’s the culture we create within a classroom.

Deep Culture: Competition

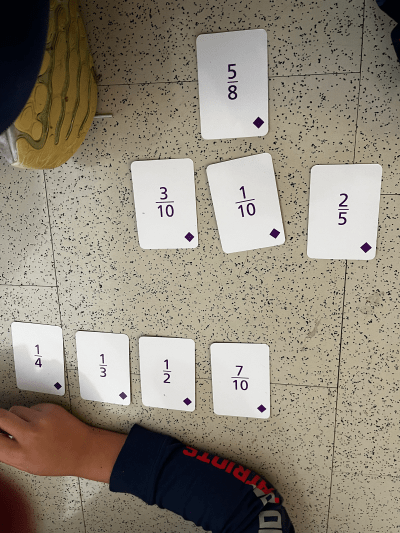

Last week, I visited a fifth grade class playing the game “In Between” (TERC Investigations, Grade 5, Unit 3). The classroom teacher was called to attend to something urgent, and so I launched the game with the students. No big deal. While I hadn’t reviewed the lesson in advance, I had played it with a different fifth grade class the previous week.

But I forgot that the other fifth grade teacher had revised the rules to make it a cooperative game. In her version of the game, students began with cards that gave the benchmarks of ,

, and

, and then students took turns placing cards on either the left or right of a card to make the longest string of numbers they could. The goal was to sequence everything without any leftover cards, so students discussed how to maximize their moves, and how to compare the values of two different cards that seemed close together, like

and

.

Now, while teaching students to play the game, I put the game rules up on the smartboard behind me, and we discovered that this is actually intended to be played as a competitive game. Oops.

So I retaught a section of it, emphasizing strategic play. Previously, if we had a card, and saw that our partner had a

card, we would choose not to play it so that we could get the

card on the line later. Now, we would deliberately behave in the opposite way. We wanted to block our opponent! Instead of sitting next to each other, students wanted to sit facing one another.

It was a small shift in game play. It was fascinating to see it play out with students, some pairs engaging in gentle competition while other partnerships seemed to relish the attack. (“Haha! Now I’ve blocked your forever!”)

Either approach seems fine as long as both partnerships agree to the tenor of the game. When there is a mismatch — one soft player and one cutthroat — is where competition can be its ugliest. Students’ internal beliefs shape how they interpret the same instructions. These internal beliefs may have been shaped by socialization based on gender, or by family cultural norms, or by larger cultural norms within society. Would the game play look identical in another school? …state? …country? Culture doesn’t fall along neat, political lines, either, so potentially it would look dramatically different in nearby settings.

There are so many choices one can make around competition — to include or exclude elements, and the tone of it. Teachers can’t fully control how students experience competition. The task’s structure interacts with students’ own cultural norms, and awareness of these differences helps teachers anticipate when friction or misunderstanding might occur.

Competition isn’t a neutral classroom variable, like how one teacher downplayed it while the other emphasized it. It’s culturally shaped, and students bring deeply held norms that can change the entire feel of an activity.

The Culture We Bring and the Culture We Create

Culture is always present: the culture we bring and the culture we create. Similarly, while there is a classroom culture unique to itself, even within that culture community members can have internalized diverse, invisible norms. We may not all have the same references, or the same ways of interacting, or the same definitions of kinship and family structures.

Dr. Seda’s talk reminded me that, when teachers make choices, we are choosing to center certain experiences. It is not that we need to disrupt the cultural majority all of the time. That would be disorienting for so many students! What if we totally inverted the local norms about honesty and personal space all the time? It would be an exhausting space.

And there exist some students outside the cultural majority — maybe they come from a different ethnic background, or faith tradition, or neurotype — and they have to experience these disruptions all the time. They learn how to code switch, which is constant, and requires high-level cognitive control. These students also deserve some affirming experiences.

When I think about changing elements of surface, shallow, and deep culture, I keep returning to this larger question: what should guide a teacher’s decision to change a cultural element? It does not mean that we need to go through every single math task we use and “diversify” it. Changing every instance of brownies in the curriculum to tiramisu doesn’t meaningfully address the experience students have as members of our classroom communities. The answer also isn’t a checklist or a directive. It’s a stance.

As an educator, I strive for intentionality and balance. I consider the goal: why this shift? And for whom? A surface change (like switching brownies to tiramisu) can open the door for one student’s participation. A deep cultural shift (like reframing competition) can change how students see one another. Are there some students that are consistently marginalized? It is not that we need to marginalize the other students in favor of those ones; instead, we consider the balance.

Cultural responsiveness feels less about getting every move right, and more about creating a positive culture that honors multiple ways of being in the same classroom. Students should feel seen, safe, and connected, no matter what cultural background they bring into the room.

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.