I recently returned from NCTM in Atlanta. It was a beautiful week of learning and connection (and late night karaoke — priorities).

“Let’s See What You’re Saying.”

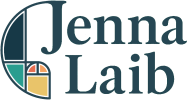

On Friday, I attended a session with Grace Kelemanik and Amy Lucenta entitled “Engage all students in mathematical ideas and processes by planning from the margins in.” (It was predictably brilliant; I love Grace and Amy’s work. Check out their books.) They shared a microroutine: “Let’s See What Your Saying.” We watched a video of the routine in action, and discussed how the teachers supported the varied needs of the students.

In the video, student work was on display. A student spoke about how they thought about the problem while another student pointed to different parts of the work to emphasize mathematical features. Then, another student rephrased the original pair’s thinking (“they noticed… so they…”), while the teacher annotated the work, with deliberate use of color.

My turn-and-talk partner and I shared what we noticed about the video: the use of sentence stems, and structured sharing, and multiple modalities.

I was also struck by how effectively this simple routine managed cognitive load. The students presenting were tasked with focusing on one form of output, e.g. just speaking, or just pointing. Meanwhile, the students listening are able to access multiple modalities (oral, visual) in order to deepen their understanding and make stronger connections to the ideas being shared. It’s so much easier to take in multiple inputs than to produce multiple outputs simultaneously.

Addison Learns How to Facilitate Number Talks

When first grade teacher Addison was new in her career, we worked together on implementing some instructional routines, like number talks and “Which One Doesn’t Belong?” Addison was instantly captivated by number talks — how her students engaged, and the quality of ideas that surfaced. “Did you hear what Roberto said?” she gushed, falling into a chair. “He barely talks in math class, but what he said was so smart!”

I modeled two dot talks for her, and then announced that it was time for her to try her hand at facilitation. “I’ll be right here to watch,” I assured her. “And you can always do a time-out to ask me questions.”

But Addison was still nervous. She was a totally competent teacher, and I offered some genuine compliments for lessons that I had seen. She felt particularly comfortable in literacy, leading interactive read alouds and small group guided reading lessons. None of that mattered in this moment. “Can you just, um, do another first?” Addison asked me.

So I did. And a few days later, when I proposed that she try facilitating, I watched her eyes grow wide and lips clench. It was like her body was emiting “noooooo” in radio waves.

“Okay,” I paused. “What if… you do the talking, and I do the annotating,” I suggested gently. “And then we can switch.”

One output for Addison. Multiple inputs for students.

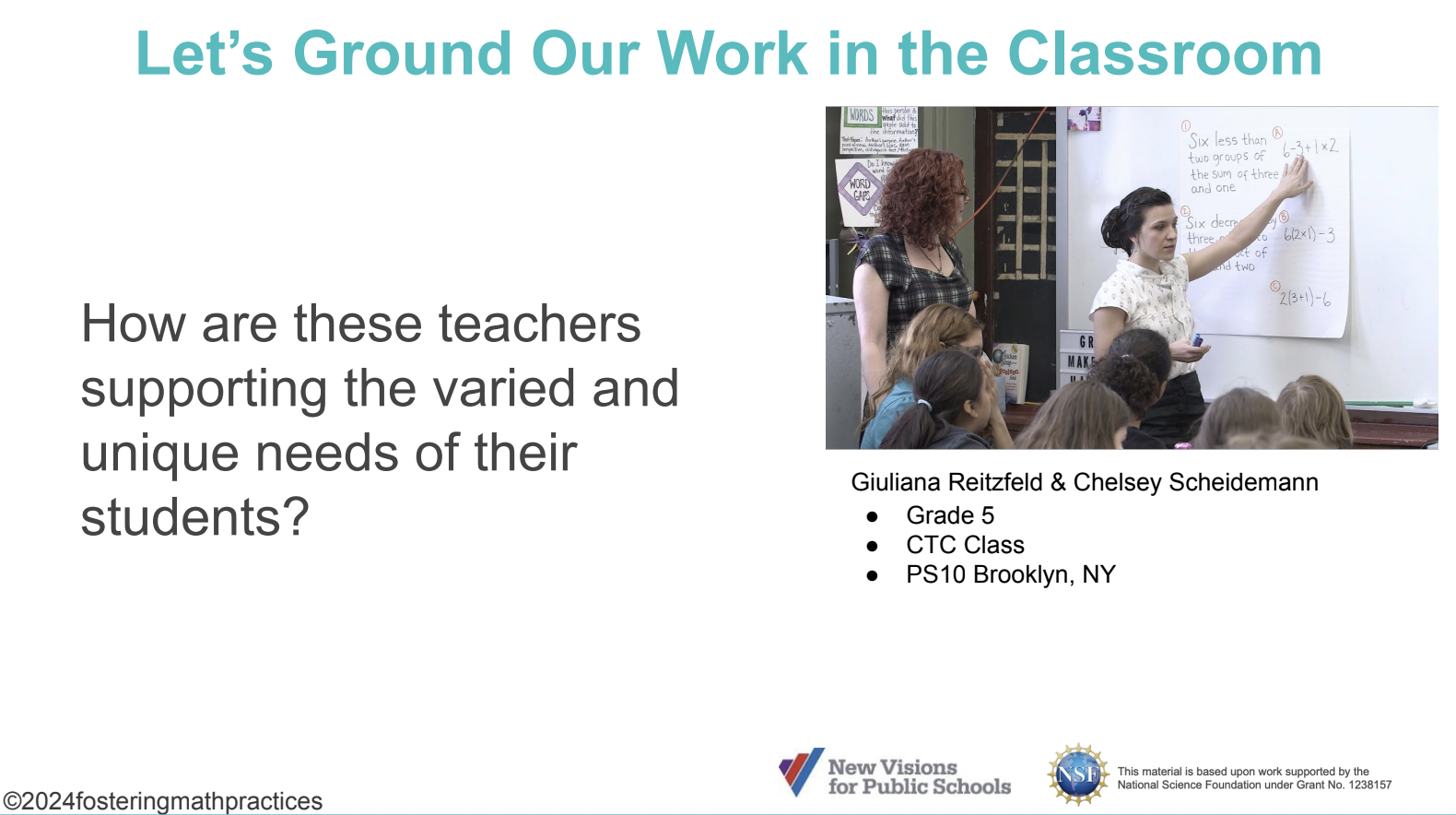

The more I thought about it, the more I saw how complex all of these various outputs were, and how they integrated many different areas of cognition.

In facilitating a number talk, we thought about:

- What to say (language)

- How to say it (language)

- Where to write or draw (visual-spatial processing, organization)

- Timing hand moments (embodiment)

- Keeping track of the reasoning (conceptual, memory)

- Asking clarifying questions to the student sharing (attention, auditory processing, conceptual processing)

- Asking deeper questions to all students (conceptual processing)

Anxiety had been hijacking Addison’s brain, and this was an opportunity for her to focus on just a few of these micro-components of the facilitation. Within two or three co-facilitated number talks, Addison was reading to go solo!

(I ended up writing a blog post about some of the facilitation work with Number Talks that Addison and I did together. In Amy and Grace’s “Let’s See What You Said,” another student rephrases the first pair’s work in order to maximize engagement, clarify ideas, and offer helpful repetition of the work. In the number talk work with Addison, we asked students to identify and describe connections between different student’s work, which served a different but similar purpose.)

Inputs and Outputs

It’s not that students should only be responsible for one output while sharing. There are times when it makes sense for students to share in multiple modalities. For example, there are times when gesturing and pointing are a key element of someone’s mostly-oral communication. It’s easier for them.

It can also be more cognitively demanding — in a good way — for the student to focus on rich oral expression. In order for a second person to point or annotate, the person providing oral explanation needs to speak with enough clarity that someone else can follow along. There are times when students ask to come to the board to draw their thinking, and I push them to continue to explain things using words. It’s a beautiful challenge.

As for inputs, multiple modalities can help in many situations. They reduce cognitive load by distributing the act of processing across different areas of cognition, and activating different neural pathways. It can build stronger memories through the act of redundancy, e.g. hearing and seeing simultaneously. But there can be too many inputs, especially if these modalities feel disconnected or too fast paced.

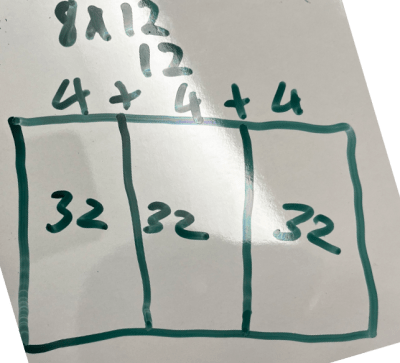

Today was my first day back at school post-NCTM. I found myself in the classroom of an early career upper elementary teacher, leading a number talk. I watched as she gave students individual think time with white boards. She asked students to represent their solution in multiple ways, and to make connections between these ways.

This student solved 8 x 12 by breaking up the 12 x 8 into 3 x (4 x 8). They then shared their thinking orally, using their whiteboard as a reference, while the teacher annotated it on the board. She added in more equations, like 3 x (4 x 8).

Inviting students to receive information through multiple modalities — inputs! — can expand access and deepen understanding. When we invite students to share their ideas — outputs! — we want to choose and sequence the modalities purposefully. This may mean just one, or it may mean multiple. It was an interesting lens to carry through my day teaching.

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.