Who makes the mathematical laws?

Autodidact Abraham Lincoln managed to become a lawyer in spite of his lack of a formal education. After serving one term in the US House of Representatives (1847-1849), he returned to his law practice and his studies. He rode the Eighth Judicial Circuit around Illinois, hearing cases by day and laboring over Euclid’s The Elements well into the night. His law partner, William Herndon, marveled over how Lincoln could “concentrate his thoughts on an abstract mathematical proposition, while [fellow lawyers and judges] so industriously and voluably filled the air with our interminable snoring.” [source] Euclid was a favorite of American “founding fathers,” too. (Jefferson cited it in a blisteringly racist passage from Notes on the State of Virginia, 1785). There are several different secondhand theories to explain why Lincoln would pursue this study, some offering parallels between the structures of legal arguments and mathematical proof.

Mathematical logic offers us a framework — and a set of governing laws. What happens when we bend them? Or break them?

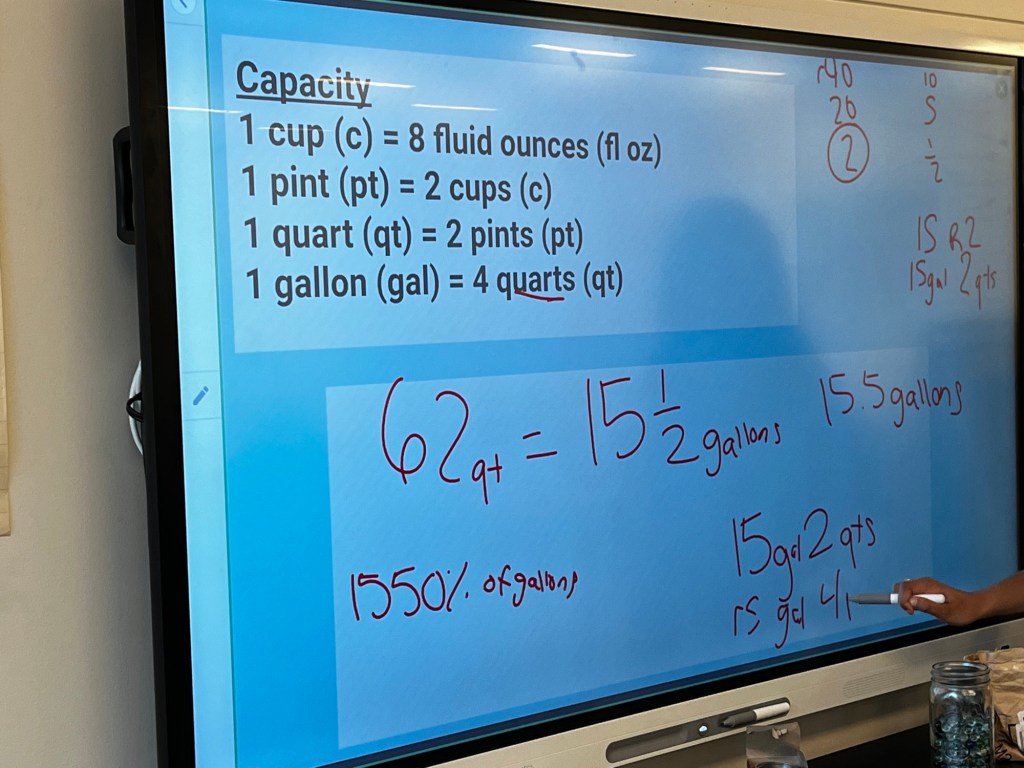

Fifth graders are working on measurement conversions, e.g. how many centimeters is 13.4 meters, or how many tons are equivalent to 4500 lbs? I can get excited about most mathematical topics K-8, but some of these measurement lessons require me to hype myself up on the way in. Maybe a kid will come up with an interesting visual representation! We can have some conversations involving estimation, and reasoning about whether a product will increase or decrease! I heard the classroom teacher created anchor charts with insta-worthy aesthetics! Maybe the endless pages of equations won’t lull this particular cohort of kids into a mathematical stupor!

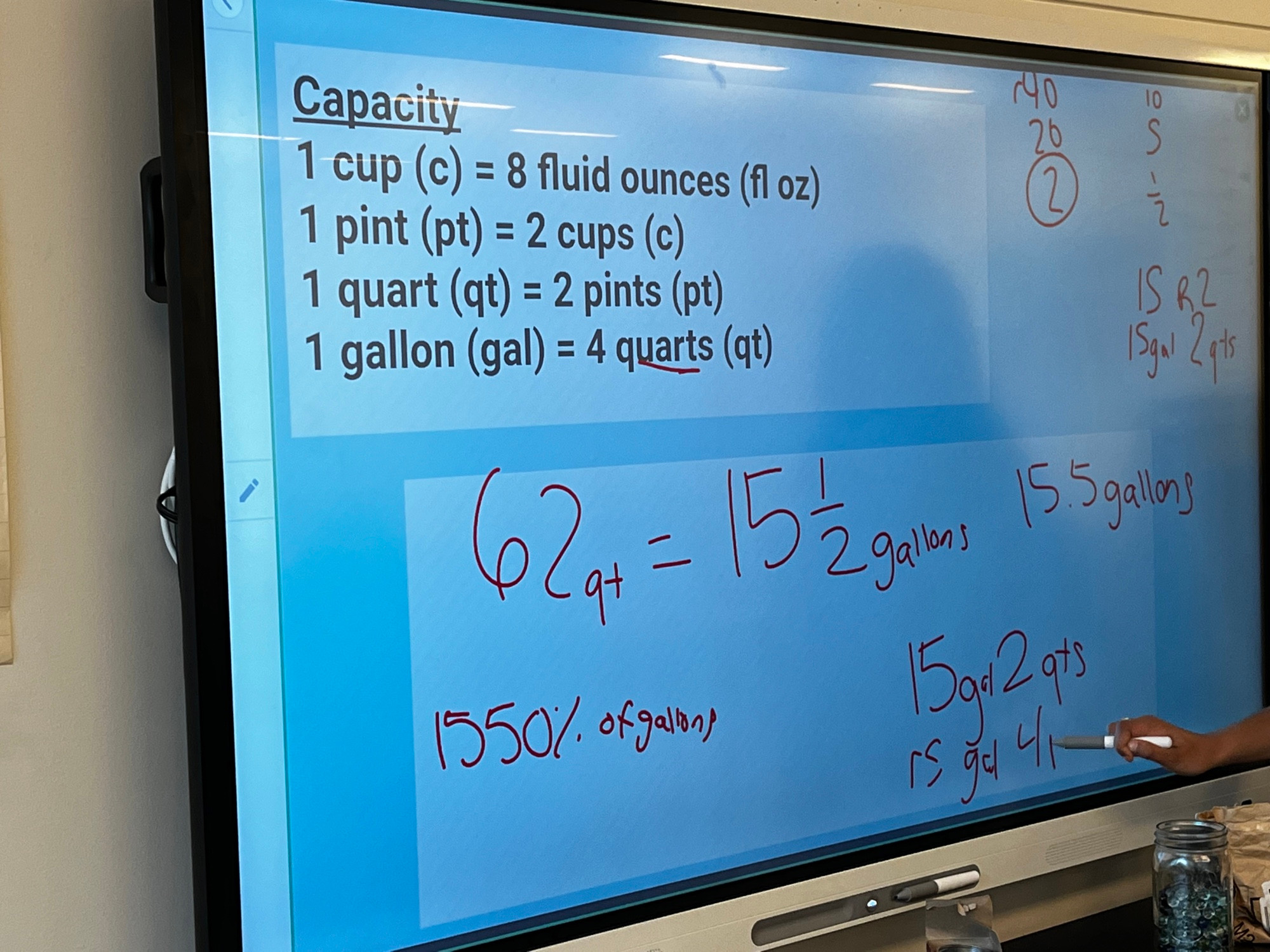

And then I get to watch everyone in the class doing 62 quarts = ___ gal.

Bah.

How Many Gallons?

The classroom teacher, Ms. Tyler, asked several kids to showcase their strategies on the board. Harry went first. He decomposed 62 into 40, 20, and 2.

Anderson used halving and halving again to divide by 4.

so

and

Willa explained why this works: “two is a… what’s the word?” (Classmates shouted out: quotient! divident! Divisor!) “No… factor! Two is a factor of four. It goes in two times. So if you divide by 2 you have to divide by 2 again to do the same thing as dividing by 4.”

I felt that twinge to go deeper — to get students to make conjectures about how we can use other factors to divide, like ÷ 2 and ÷3 to divide by 6, but it was truly not the point of the lesson. Wisely, I bit the inside of my cheek.

Equivalent Answers

Ms. Tyler helped the kids compare and contrast their strategies. Then she pointed out that their answer, , can actually be written in several other forms. “How else could we say

gallons?” She gave them some time to think, and then turn and talk to share.

Willa and Anderson turned to one another. “15.5,” Willa said, with a raised eyebrow that seemed to nudge Anderson: “you’re turn.”

“15.50,” he chuckled.

“15.500,” Willa countered quickly.

“15.500 repeating,” Anderson added, using a mini whiteboard to record his thinking. He drew a bar over the two zeroes. They exchanged satisfied grins.

I circulated around the room to listen in to Bennett and Celeste. “15 gallons and 2 quarts,” she offered.

“Oh, and two quarts is… 4 pints?” Bennett searched her face for reassurance. She nodded. “So it’s also 15 gallons and 4 pints.”

“We could change it all into pints,” Celeste suggested.

Ms. Tyler called the class’s attention the board, and accepted some answers.

Students shared the ones that I had already heard surface, although I was pretty stunned by Willa’s offering of “1550%.”

1550% of what?

“Of gallons,” she replied.

Incredible! 100% of one gallon is 1 gallon, and 200% of one gallon is 2 gallons, so 1550% of one gallon is 15.5 gallons. To find a percent equivalent for a decimal, multiply by 100: and . While “of gallons” wasn’t sharp and precise, it was an impressive answer! We were following mathematical laws while ever so slightly bending them. I quickly snapped a photo.

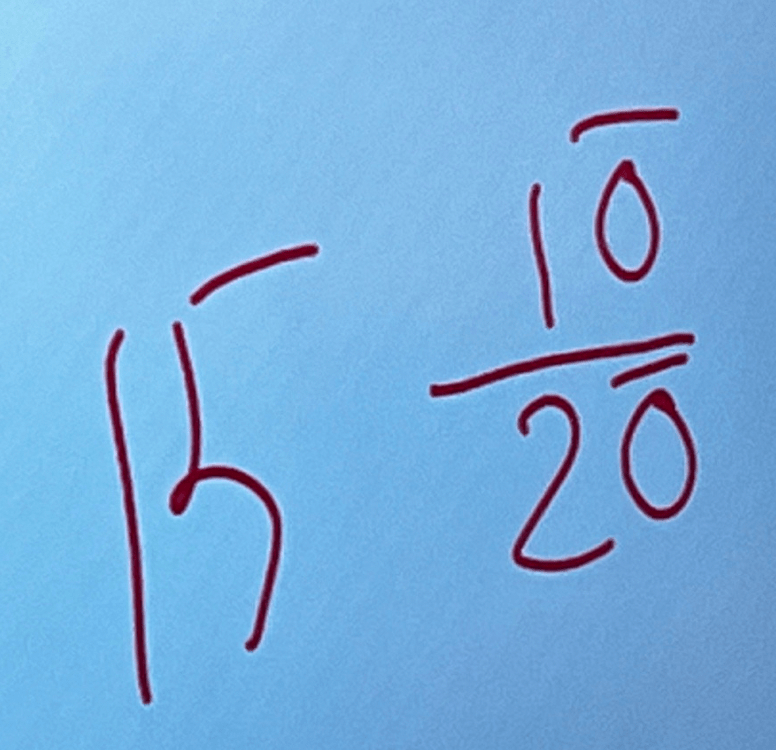

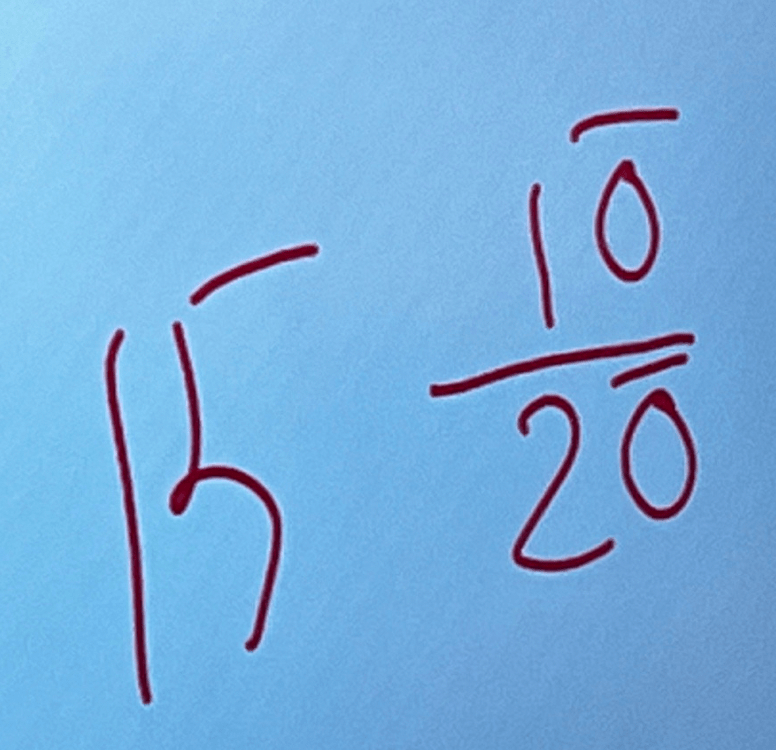

Then Anderson asked to come to the board to show his.

What.

Bending and Breaking Mathematical Laws

We use bars to represent repeating decimals, and decimals are really fractional parts of whole numbers, but… what is a fraction bar in this context?

And, indeed, every time we append a zero we are multiplying by another ten. As long as we multiply the numerator and denominator by the same power of ten, we are generating an equivalent fraction.

But what about ? Can we allow infinity to act like a constant?

But did Anderson mean ? Or did he mean to express that you can append any number of zeroes, and as long as the zeroes match, the fraction will be equivalent? Like shorthand for

Nope. “The zeroes are endless!” Anderson announced proudly.

Honestly, it followed the same internal logical systems we were familiar with, while also breaking the rules. It reminded me of a delirious late-night conversation with my brother Ben and his HS friend Jeff, documented in an OG ‘Math With Bad Drawings’ blog post aptly titled “Kaufman decimals.” We had explored metaphysical properties of decimal repetitions. Here we were on the other side of the decimal point, wrestling with the idea of a digit followed by endlessly repeating zeroes. That’s not infinity. But also… it’s not not infinity?

And in the context of a relationship or ratio, like , does it make more sense than

(with a bar) alone?

Lincoln wasn’t a mathematician, but something drew him to Euclid’s texts. He engaged with a scholarly rigor, to learn about logic and structure and rules.

Anderson here was playing around with quantities. He’s exploring the edges of mathematical rules by bending and breaking them.

Ms. Tyler expertly addressed it — talking about ‘legal’ mathematical moves, almost like a game of chess — and then, just as expertly, moved on. Students examined strategies for dealing with decimal divisors. Hard work. It was, without question, the right decision for the pacing of this particular lesson. The goal is to push student thinking forward, not to indulge my own mathematical interests. Still, I let my mind linger on Anderson’s endless zeroes. How do we wrestle with the idea of infinity in elementary school? How do we try to understand it? And when do we push an entire class to fall down that rabbit hole?

To Infinity…

I don’t know how Lincoln maintained his passion for Euclid — studying by candlelight, many years before the invention of the incandescent lightbulb. As I said, there are several secondhand theories to explain why Lincoln was so insistent on this study, and among them is the idea that it was for personal satisfaction. It was a realization of his own ambition — the infinite pursuit of knowledge and wisdom and growth. As we navigate the potentially infinite space of learning, how do current mathematical rules apply? What can we learn when we bend them?

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

It’s like a cartoon identifying future mathematicians. I tell my learners how much I love math trash talk, and this is right there. Can feel their joy popping out of the story.

LikeLiked by 1 person