How do we support students who are struggling to access grade level content?

In my own school, I focus my efforts on co-teaching and coaching, but I also see students for intervention, both individually and in groups. There has not been a lot of guidance around what this intervention time should look like. In the past, I was more likely to use a curriculum, and attempt to “fill in gaps.” It was a clinical model. Liliana is struggling in 7th grade math and can’t identify whether a fraction is greater or less than a half? Let’s start there: fractions, fractions, and more fractions.

That said, the phrase “we have to meet kids where they are” sets off an irritating buzzing in my brain, like a mosquito or a house fly. There’s something innocuous about the idea — let’s honor their past experiences by starting from a more comfortable place — but, in practice, it can cut students off from grade level content, lowers expectations, and reinforces bias against our most vulnerable students. If Liam is an 8th grader who struggles to subtract within 20, focusing exclusively on that subtraction work will feel distant and disconnected from what’s happening in 8th grade. The gap gets wider.

So what do I do doing intervention blocks. Well, it depends. But here’s one story about my time with Tomás*.

This post is my first of two about my work with Tomás. This one will focus on intervention and making mathematical connections. I fully recognize that I may decide later — in three weeks, or three months, or three years — that this approach to intervention isn’t working at all. Regardless, I hope the data will show that Tomás benefited from these sessions. And, for now, I am sharing it as an example of making connections between different mathematical topics, skills, and understandings.

Introducing Tomás

Sixth grader Tomás and I see each other a lot. I co-teach his sixth grade math class, and then we currently have a few additional times to meet one-on-one for support. Honestly, these are some of the most beautiful moments of my week. Tomás is all smiles and kindness and light. He arrived in this country with a history of interrupted schooling, and he has expressed that math “is not his favorite subject,” but he never shies away from it during our work together.

Planning

As I’m planning for each session with Tomás, I think about how I can help him scale through learning progressions. It can feel like mathematical mounting climbing. We begin at the base of the mountain — grade 1 place value work, let’s say — and quickly ascend up the learning progression toward grade level concepts. It’s a steep but not unnatural climb.

Right now, we begin each session with a quick estimation and counting activity. I use it to reinforce ideas about quantity, place value, multiplication, writing expressions… there are so many connections we can make. My job is to connect these concepts to what we are doing in sixth grade, increasing his access to grade level content and providing some needed practice.

What I will share in this blog post is far from perfect. I could have finessed the language I used, or the tasks. The reason I share is to show a potential pathway up the mountain, from first grade place value to sixth grade geometric measurement. The more that we see potential pathways like this, the more that we find our own. (And perhaps you will do execute it with more finesse!)

The Base: Estimation

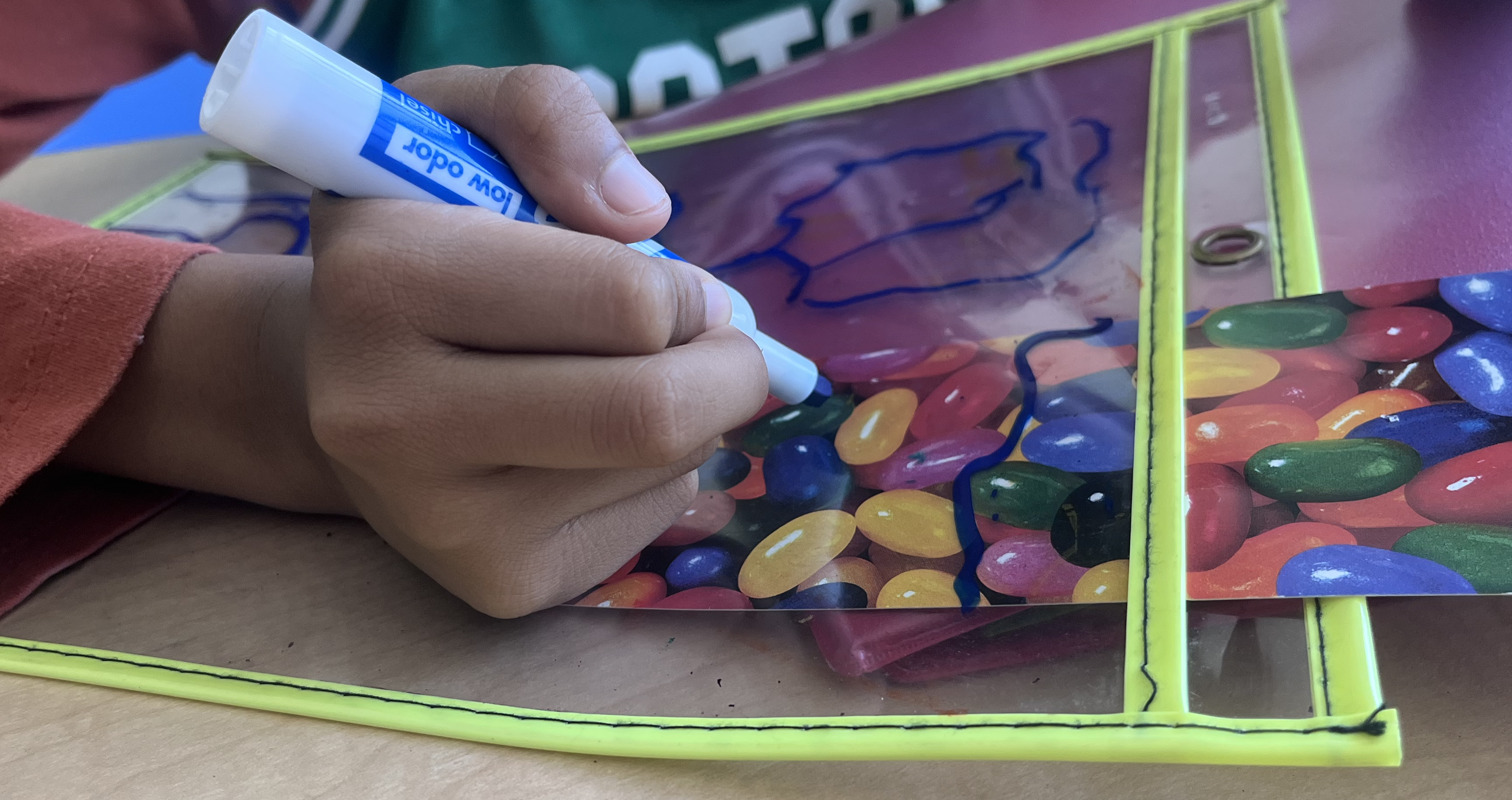

During our very first time together this year — in mid-September — I showed him a strip of bulletin board border paper I had found it in the teacher workroom donation pile. It featured a wild and colorful collection of jellybeans. How many jellybeans do you think there are?

“30?” he offered a strained smile, ever so slightly gritting his teeth. He wasn’t sure.

I circled a group of ten. “Okay, so this is 10 jellybeans. Let’s use it to help. How can you use the 30 jellybeans to estimate how many jellybeans there are in all?”

Tomás paused, then began circling groups of 10. After three, he paused. “Oh, that’s 30.” A beat. He looked at me expectantly.

“Yeah, that’s 30! And is that all of the jellybeans? ¿Es todo?” I asked. Tomás shook his head no, hiding behind a shy smile and a turned head. “That’s okay,” I continued. “Now we know what 30 looks like. You have three groups of 10.“

“10 + 10 + 10.”

“Yes, or we could think of it as three times ten. In sixth grade, you need to be looking for opportunities to multiply.”

We Ascend: Connections to Multiplying by 10

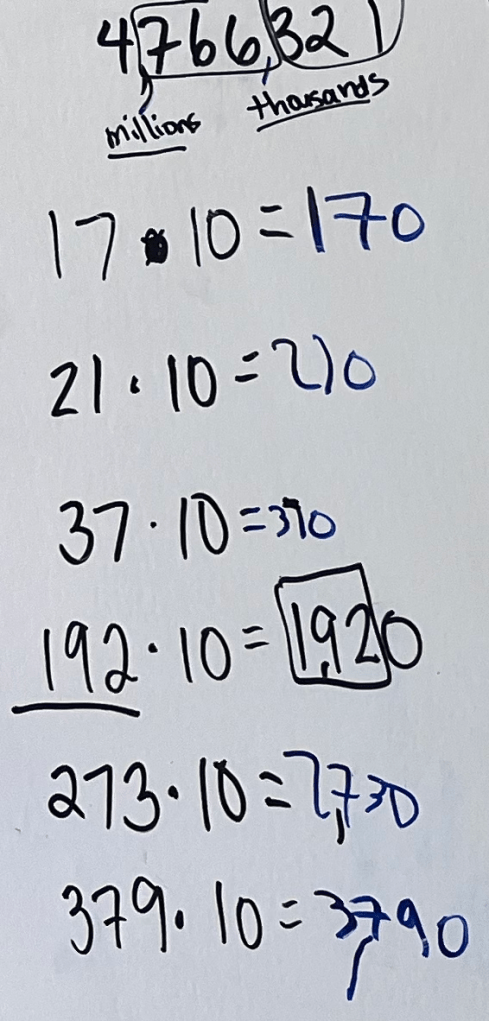

Sixth graders are expected to perform operations with decimals fluently, building off elementary understandings of place value. In fifth grade, students multiply numbers by powers of 10, and explain patterns in the placement of the decimal point when a decimal is multiplied or divided by a power of 10. Tomás attended fifth grade at my school, and also I saw him struggle through 5 x 10 earlier that day.

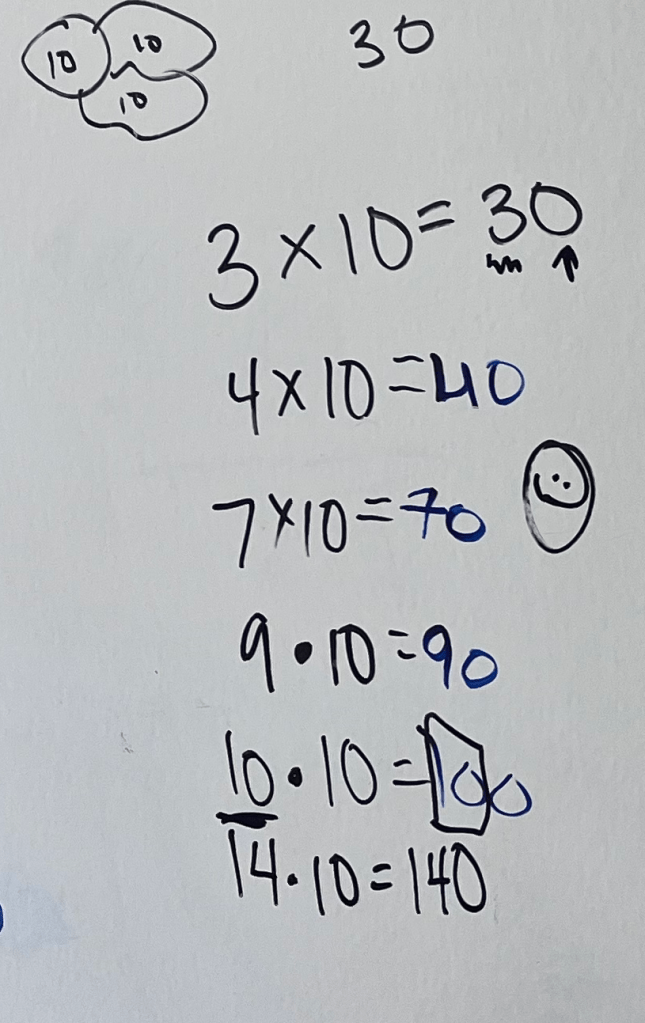

What did he know about three groups of 10? I wrote on the board. “This reminds me of work you were doing in class earlier, with multiplication and the area of parallelograms. To find the area of a parallelogram with a height of 5 and a base of 14, you did 5 x 14, which was 5 x 10 and then 5 x 4, but you got stuck on the 5 x 10.” He nodded. I brought him over to the board to solve a few problems multiplying a number by 10. He seemed to have memorized the products of 10 and all the one digit numbers.

“Let’s keep going, only now let’s use the dot for multiplication instead of the ,” I told him. I try to be as explicit as possible about how symbolic representation and notation. The way that we write mathematical ideas over the course of middle school gets increasingly abstract.

“What about ?” I asked. I watched Tomás use his fingers to keep track of his skip counting: 10, 20, 30, 40…

He recorded the 100, and I asked him to look for a pattern. “7 times 10 is 70, and… oh, it’s like 7 times 1 and then a zero. And 9 times 1 and then a zero. It’s number and a zero.”

“What do you notice about 10 x 10?”

“It’s a 10 x 1, and then…” he trailed off.

I enclosed the first two digits in 100 in a box. “This is 10 in the tens place. Ten tens. That makes 100.”

“Oh, it’s a ten and a zero.”

“Yes, and you’ll hear Ms. S talk about attaching or appending a zero later in the year. It’s that same idea.” I considered how I talk with upper elementary kids about place value, but all the words coming into my head were just so… so… wordy. With Tomás, I try to be precise while streamlining my language. I moved on. “Now how about ?”

Tomás looked at me baffled. I offered to write the product, but he’d have to explain how it follows the pattern he noticed earlier. He nodded. Smiled.

“Oh, it’s a 14 times 1 and then the zero.”

I decided that we’d return to the jellybeans, and then back to the multiples of 10 and 100 with whole numbers in order to examine place value. Ultimately, in a

Up the Path: Making Groups of Jellybeans

“Okay, let’s look again at the jellybeans. You circled 3 groups of 10. How can we use that to revise our estimate? Revisa tu estimación“

Tomás paused, and picked up the dry erase marker again. He circled group after group of 10, double checking to make certain he didn’t have an errant group of 9 or 11.

Eventually, he had to rotate the image — part of it had been hanging over the edge of the dry erase pocket, and he wanted to be able to annotate on it. After circling as many groups as he can, he pointed to the final 3 jellybeans. “I still have these.”

“Oh! Is that another group of ten?”

“No. It’s… 3.” He recorded his thinking, and immediately began to skip count. He recorded each multiple of ten in black.

10, 20, 30, 40…

…until he he hit 150.

“It’s four, not three,” he giggled, as he crossed out the three.

“Yes! We can always revise. Siempre.”

“Is it 1..5…4?” Again, I could sense him trying to read my microexpressions like tea leaves. He was trying desperately to divine whether he was correct. “Fifteen four?”

Going Higher: Reading Larger Numbers

So Tomás needed to work on reading numbers. This is something that happens in early elementary school, and it will still impact him now that he’s in middle school. I decided we’d focus on whole numbers.

I wrote out a place value chart with ones, tens, and hundreds, and helped him read out 154.

“But, of course, numbers can get much, much bigger. And we chunk it out like this…”

I wrote out thousands. Millions. Billions. I showed him how, in the US, we use commas to delineate the place value. So 1566998385 can be written out as 1,566,998,385, and every time we hit a comma, we say that period’s value.

1,566,998,385

1 billion, 566 million, 998 thousand, 385

We practiced reading a few numbers, generating digits randomly with dice.

I took out a notebook and recorded “reading numbers” in our list of things from the session, right under “multiplying by 10.” We would need to return to this concept during our next session, to give Tomás space to forget enough that we’d need to practice retrieving the information.

Continuing the Climb: Multiplying Larger Numbers by 10

We tried multiplying by 10 a few more times.

“What about 17 groups of 10?” I wrote out , before sloppily writing over the

to make it

. I want Tomás to get accustomed to seeing multiplication written in this way.

He built off our work and recorded . We continued with a few more two-digit factors:

, then

…

“Okay, I think you’re reading for something even bigger.”

“Bigger?” His eyes widened.

“Oh, no, I don’t know that,” he laughed. He snapped the cap back on the marker with a satisfying click. Sometimes, it’s too easy to quit.

“Okay, I’ll write the product, and your job is to figure out why that makes sense. Cool?” I extended the invitation with an ever-so-slightly raised eyebrow. He accepted.

“Oh, no, that’s so big!”

“Let’s practice reading it. This is much smaller than the numbers you were just reading. Try it.”

“1… 9 hundred 20?”

“What do you say at the comma?”

“One… thousand? Nine hundred twenty.”

“Nailed it. And why do you think this is the answer? Do you see any patterns?”

He paused, then offered: “It has the 192 and the 192 again.” I annotated on the board.

“1,920 is 192 tens,” I added. This wasn’t my most eloquent explanation, but I was nervous that more language would thin out the mathematical thread we were working on. I considered drawing a place value diagram and showing shifting place value, but instead I focused on the no-frills version we had right now. We had more content to address later in the session.

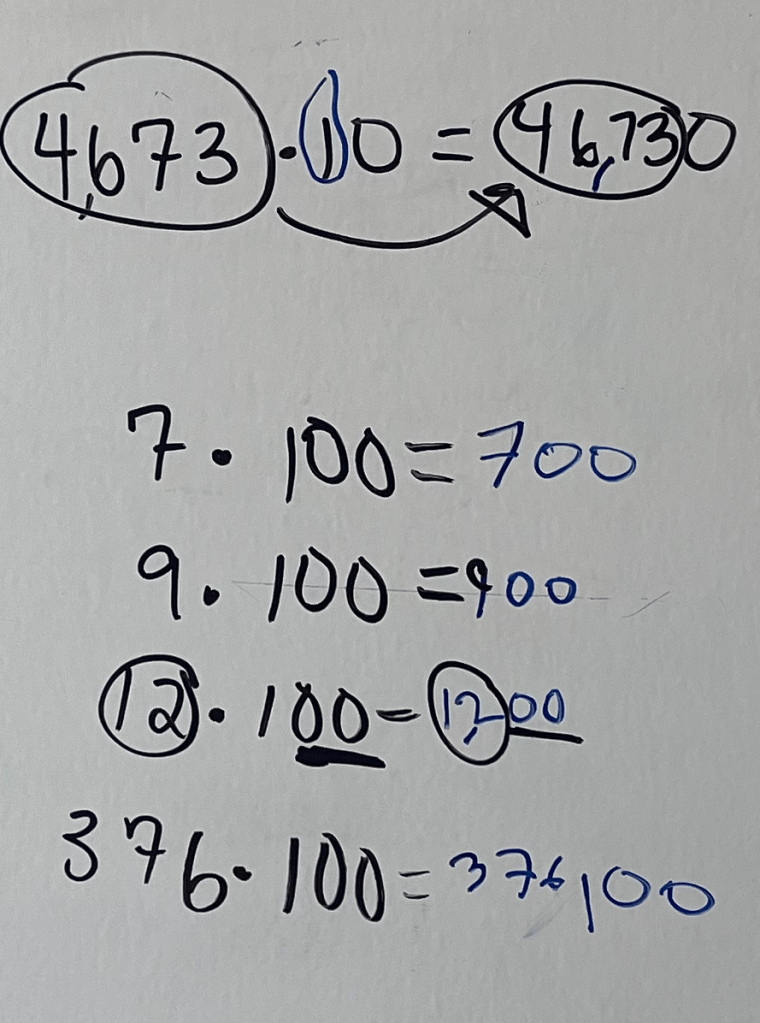

But first, we’d quickly touch on multiplying by a multiple of 10: one hundred. He quickly caught onto the pattern. We would continue to work on place value concepts in future sessions — I recorded it in my notebook — but, for now, we would continue to scale towards sixth grade content.

Moving Towards Grade Level Content: Areas of Parallelograms

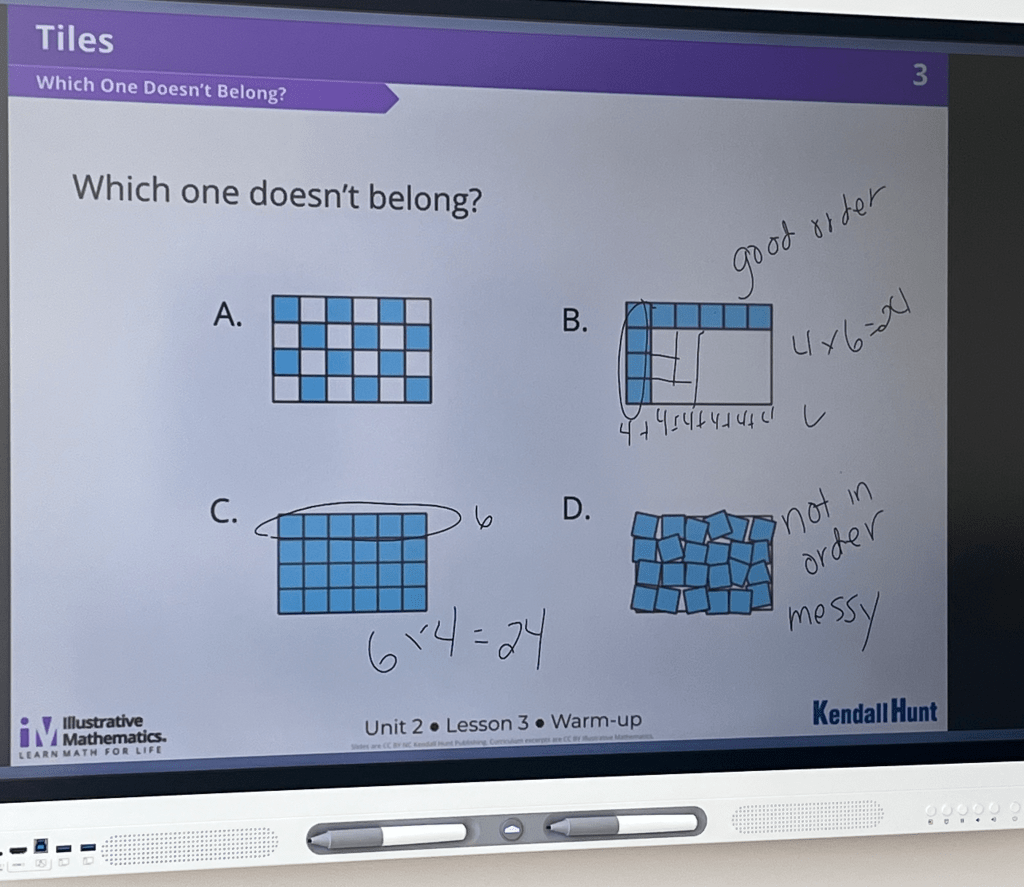

Tomás’ class was studying the area of polygons, specifically parallelograms. I pulled up some third grade content to help solidify the concept of area.

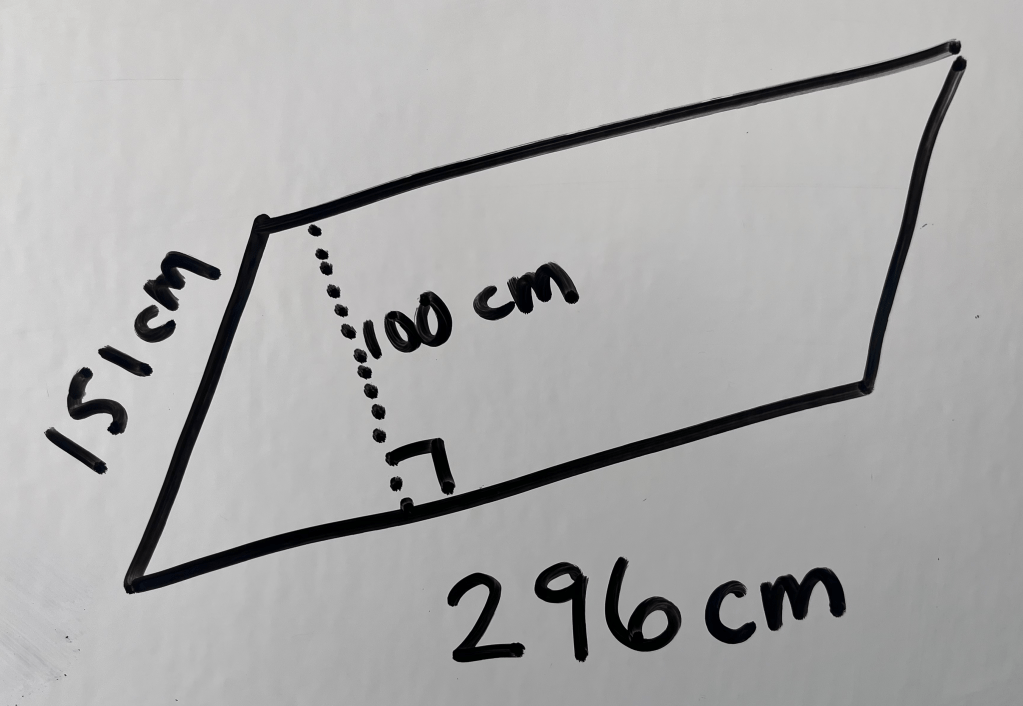

From there, I asked Tomás to find the area of some rectangles and parallelograms, including some off-the-grid, with a base or height that is a multiple of 10.

We were hitting sixth grade standards!

Retracing Our Steps

That last problem gave Tomás the chance to calculate area, multiply by a multiple of 10, and rehearse reading a large number. It’s a straightforward problem, that doesn’t inherently have a lot of cognitive complexity, but it allowed Tomás to integrate many different skills and concepts from over the course of our block together.

From estimating, to making groups of 10, to multiplying by 10 and 100, to wrestling with place value, to reading numbers, and then from third grade understandings to touching on sixth grade understandings… the block had felt somewhat frenetic. This wasn’t a leisurely Sunday morning climb, it was a full sprint. I’ve heard that if the teacher is tired, it may be they’re the ones doing all the work — implying that we are robbing students of their opportunity to think. There were moments during the block where I felt like I pulled Tomás along the path, but there were also times that I felt more like a guide.

Again, this blog post is far from a model of perfection. There were moments when I felt myself stumbling for language, or moves I wish I had made differently. Tomás and I have plenty of things to work on. But still: this is one trail up that mountain. Examining content connections, learning pathways, and progressions make them more visible to us in the future, when we are in the moment with a student and need to figure out what to do next. It’s a healthy exercise for our teacher skillset. Pretty soon, scaling the mountain feels like second nature to us, and we can focus on supporting others on their climb.

*Students are always referred to by pseudonyms, with identifying details changed.

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.