Over the years, I’ve come to call word problems ‘story problems,’ even though the story can be pretty weak. “There are 5 balloons. Three are blue, and the rest are red. How many are red? ” There’s no beginning, middle, and end there. This wouldn’t get a feature spot on the Moth Radio Hour.

But that’s okay! We’re giving kids a taste of mathematizing the world. In Kindergarten, we’re starting to formalize these mathematical situations — for perhaps the first time. We ask kids to solve the problem, and show how they solved it. We are starting to include equations alongside their work. They will continue to work on representing ideas and connecting representations throughout their K-12 experience.

Lights, camera… action!

I use the CGI problem types to frame my thinking around story problems (Carpenter, Fennema, Franke, Levi, and Empson 1999). The story problem types for addition and subtraction are:

- Joining (Adding to)

- Separating (Taking from)

- Part-Part-Whole (Put Together/Take Apart)

- Compare

You might have noticed that the first two problem types are listed as verbs in the progressive tense — which is to say that they end in ‘ing,’ implying a continuous action. Joining. Separating. These problems still wouldn’t get optioned into a movie, but there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end. In fact, students might have to figure out a missing quantity at any of those places: the beginning (start unknown), the middle (change unknown), and the end (result unknown).

The Red & Blue Balloons story problem, at the beginning of this post, has no action. It is a part-part-whole (put together) situation, in which a quantity is unknown.

There are 5 balloons. Three are blue, and the rest are red. How many are red?

Here, a student modeled it with a drawing and an equation. Because there is no action, it’s pretty clear what to draw: a bunch of balloons. Five of them, to be precise.

But not all stories are that simple. Some of them have action, and action is a lot harder to represent.

The Problem with Balls

Let’s get this out of the way: yeah. I teach middle school. I wouldn’t dare bring a story about balls out of the kindergarten wing of our school.

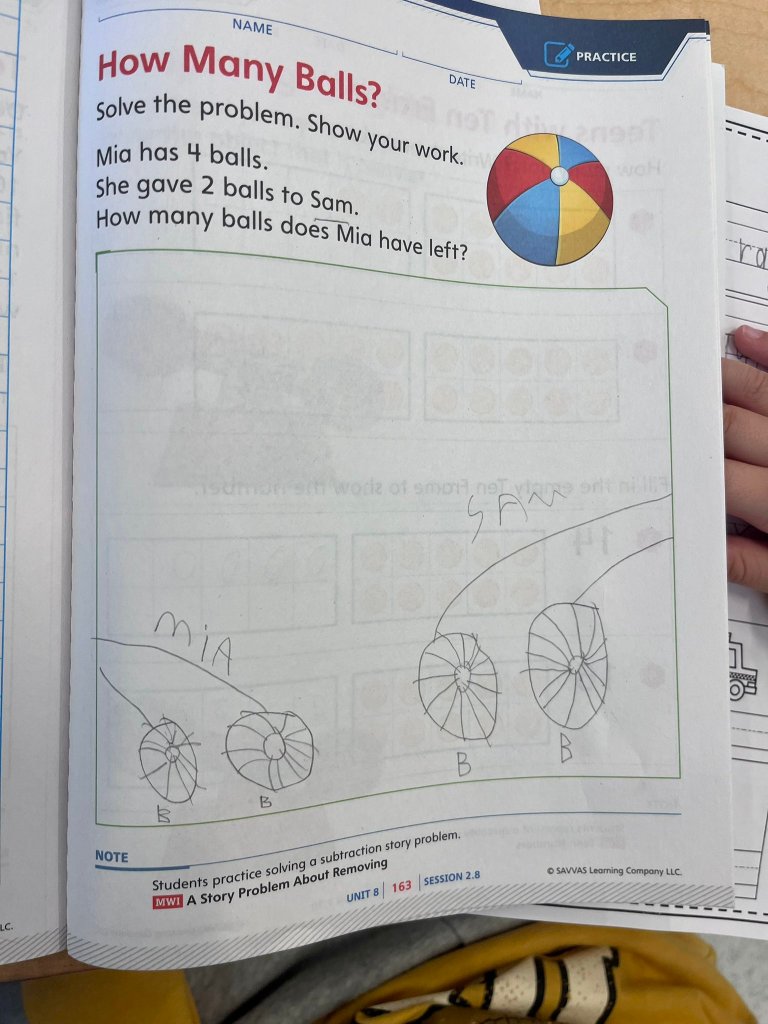

Last week, we gave our kindergartners the following problem:

Mia had 4 balls.

She gave 2 balls to Sam.

How many balls does she have left?

The problem is not that balls are harder to draw. (I know.) The problem is that students have to figure out how to draw something that deals with the dimension of time. How will they show that Mia had some and gave some away, when we can’t see the action?

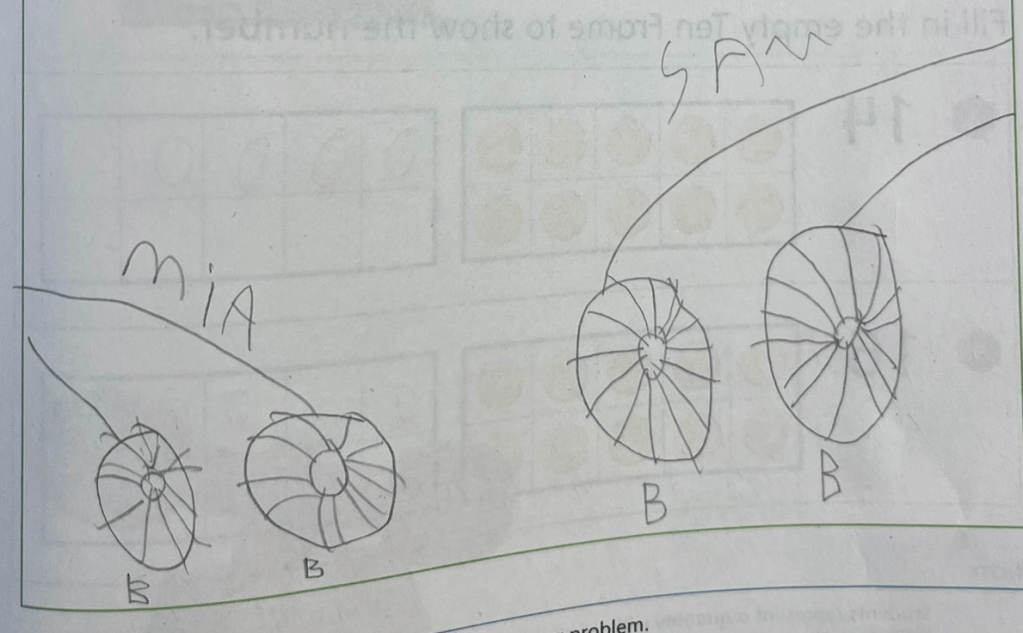

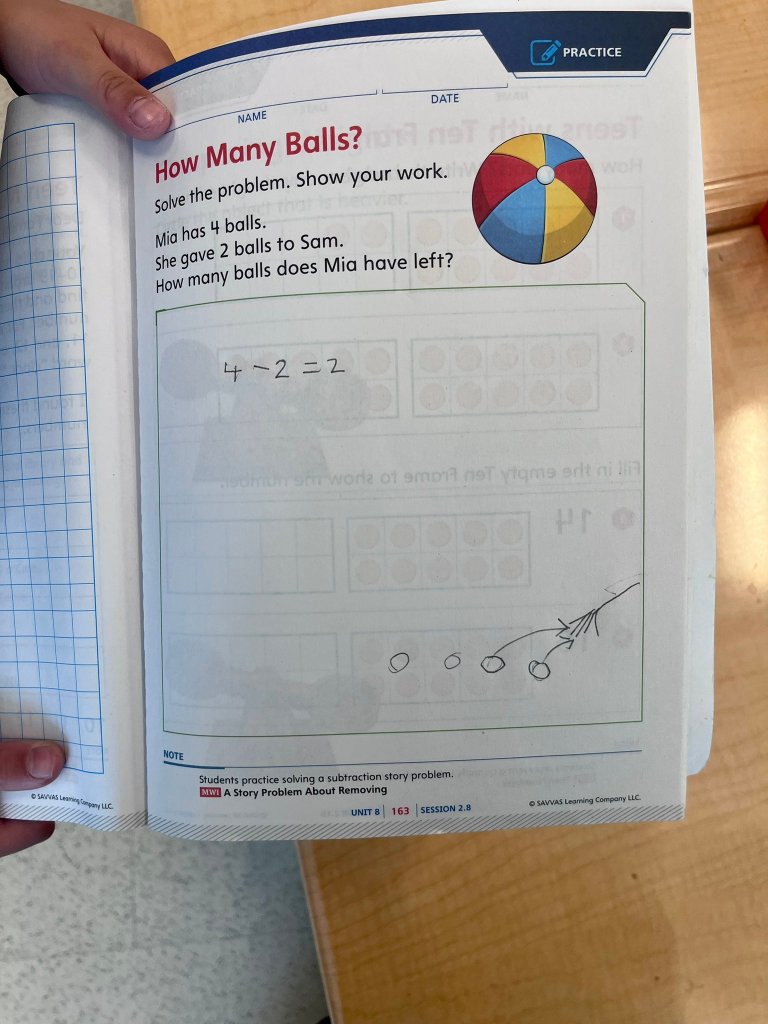

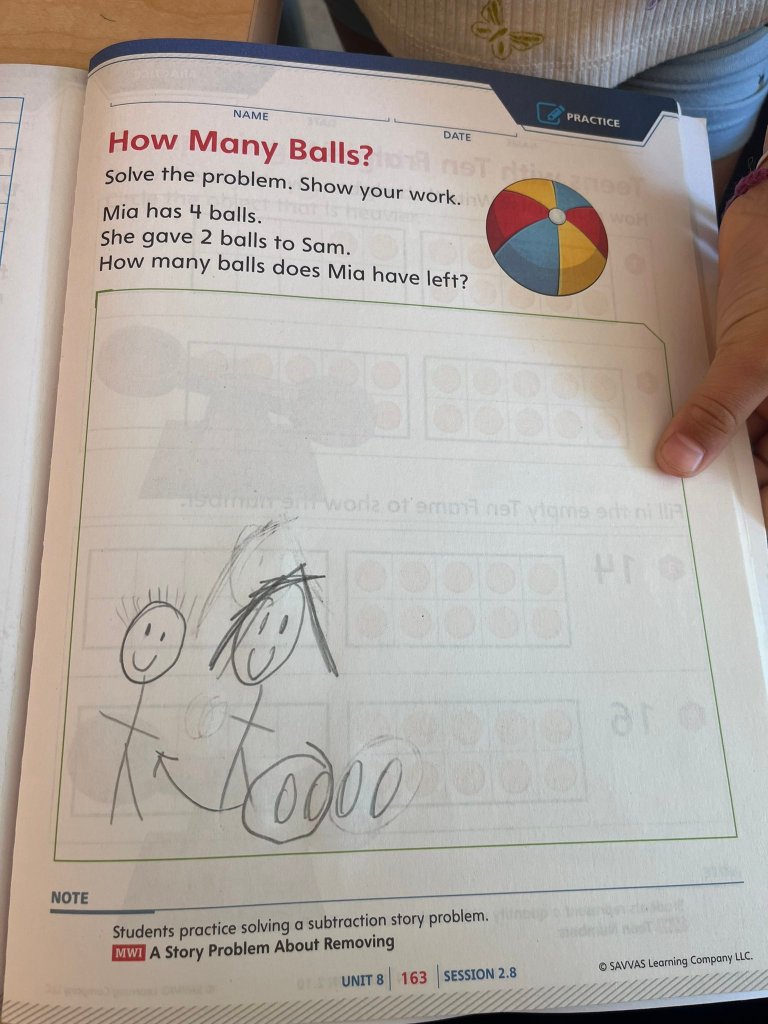

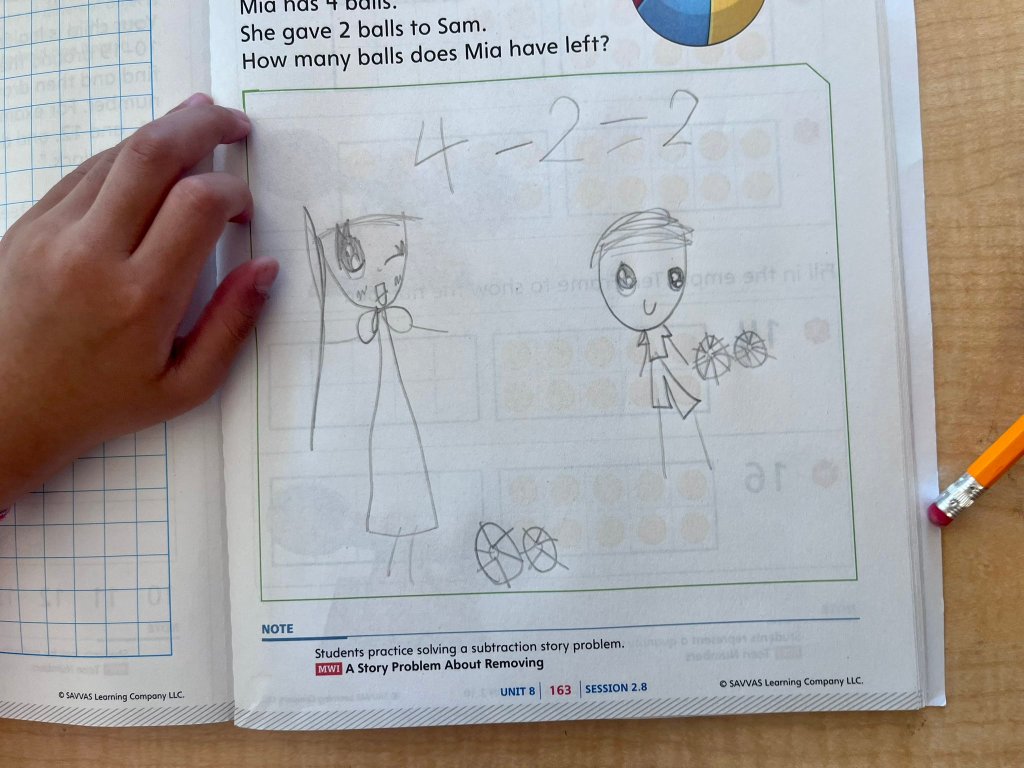

Here are six student work samples:

Who showed the action? Who showed the end result? How did students reconcile with both?

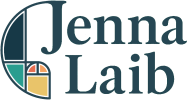

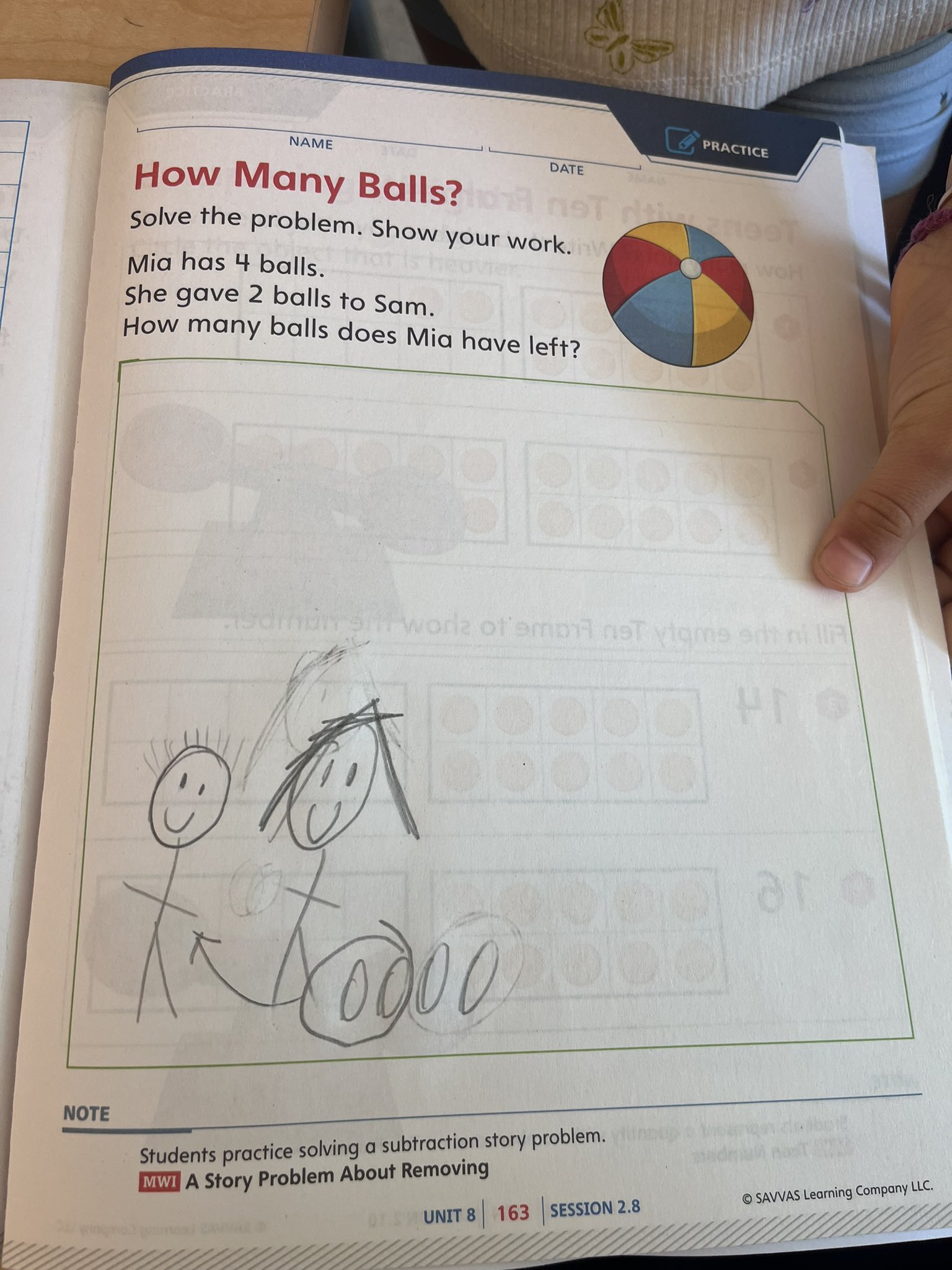

Work from Maxim and Peter

Maxim’s drawing didn’t match the quantities given in the story, but the way he showed the action was beautiful. Here we can see Mia on the left, with all of her balls. (I know.) I think she’s denoted with longer hair. (My best guess is that Maxim made some assumptions about gender based on the names, and also about gendered hair styles, but I could be wrong!) Two balls are circled, with an arrow indicating a transfer of ownership to a humble and grateful Sam. (I don’t just overanalyze the gender of these stick figures.) Maxim added in an equation: 5 – 2 = 3.

Peter’s work featured similar hairstyle assumptions and a similar arrow to show that Mia gave two of the balls to Sam. This time, they were circled instead of crossed out. It looks like Peter initially circled Mia’s remaining two, but made the decisions to erase that ring, so that the circle just shows the action.

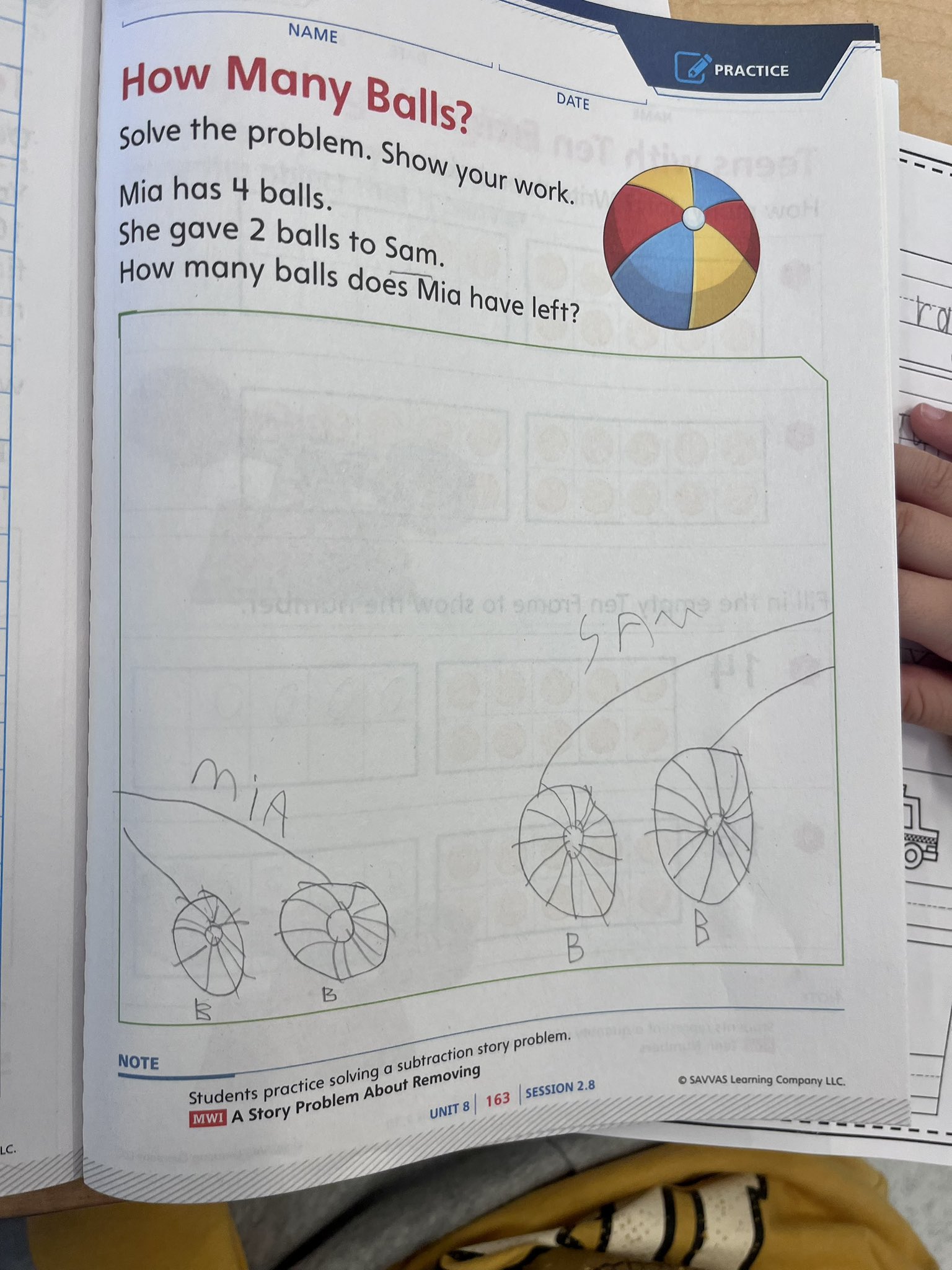

Kamala’s Work

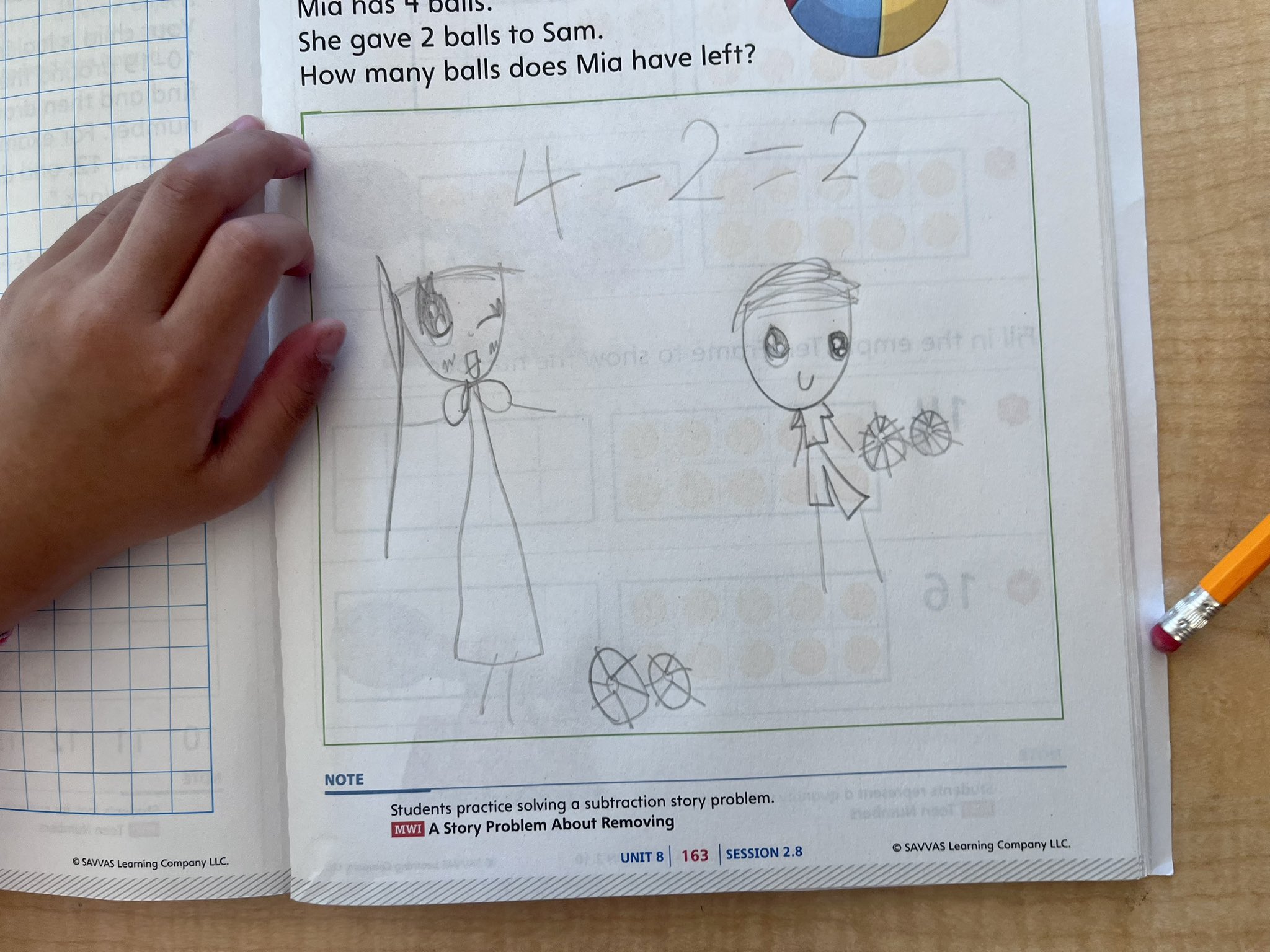

Kamala focused on the end result of the story. Mia has two balls, and Sam has two balls. (Moving on, everyone.) If we were to use the equation 4 – 2 = 2, we could see that there are 4 balls in all, and that after Mia gave 2 to Sam, she had two left.

Closing the Lesson

I wrote 4 – 2 = 2 on the board.

“We are going to take a look at some of your work,” I told the kindergartners.

“My work?!” Sam blurted out. He already felt a great deal of ownership over the problem, since it featured his name.

“I spoke with four of you about showing your work. Some of you drew the action of Mia giving the balls to Sam. Some of you drew what it looked like after Mia gave the balls to Sam. Let’s see how their pictures match the number sentence 4 – 2 = 2.”

I showed two student work samples that showed the action (Peter and Ryoko) and two that showed the final result (Kamala and Akane).

How did Peter and Ryoko show the action of giving away the two balls? Where do we see the 4 – 2 in these drawings?

Where do we see the 4 – 2 in the work from Akane and Kamala, since they didn’t show an action?

Representing Stories

Primary grade teachers spend a lot of time with students working on how to represent mathematical situations. These kids are simultaneously working on how to draw with more detail, in an artistic way, so it would make sense that they’d want to employ these burgeoning skills in math class. However, using these artistic techniques in math class can be time consuming, and take the focus away from the math.

Ultimately, this sketch that I made in, I don’t know, 1.7 seconds, conveys all of the relevant information.

Students need to focus on clarity over all else, but also that can leave some kids feeling like their work is lacking. It’s helpful for even our youngest students — in Kindergarten! — to compare and contrast one another’s work samples as they figure out effective ways to communicate their ideas.

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.