Third Grader Owen was ready for third grade math a while ago. I only met him recently, but I’m guessing he was ready in… second grade? First? It’s unclear.

Something I love about Owen is that he might be ready for more on a daily basis, but he’s not dismissive. He’s playful. His classroom teacher and I have encouraged him (and others) to mess around with the mathematics in class in different and interesting ways. I try to give him little challenges, sometimes whispered as I walk past his desk.

“I wonder if you could come up with an answer that isn’t written in eighths.”

“I wonder if you could come up with an answer where all of the digits you use, in both the numerator and the denominator, are smaller than 6.”

In the last week, I’ve noticed that Owen was already hard at work on extending the task by the time I made it over.

I’m not saying that these little dares and little challenges will work to spark thinking for every child in the class, but I am saying that there are kids like this who are eager and ready. “Sure,” you might think. “It’s easy to support the kids that are interested in math.” But I that many teachers assume that extending thinking means giving students an entirely new task, that they have to prep, and it feels like it’s adding more and more and more onto the plate of both the teacher and the student.

So how can we nudge student thinking forward, and towards creativity, with smaller teaching moves?

Here’s what it looked like last week with Owen.

Setting the Stage: Equivalent Fractions

I have been working with this class for a few weeks, but I missed about two weeks of instruction to recover from a concussion (ouch), and the classroom teacher was out with COVID for another week. In the lesson the previous day, some students had written that is equivalent to

. We knew that we needed to give at least a few more opportunities to work on this. The classroom teacher and I were planning quickly, right before class.

We launched the lesson with choral counting by s, nudging students to name equivalent values.

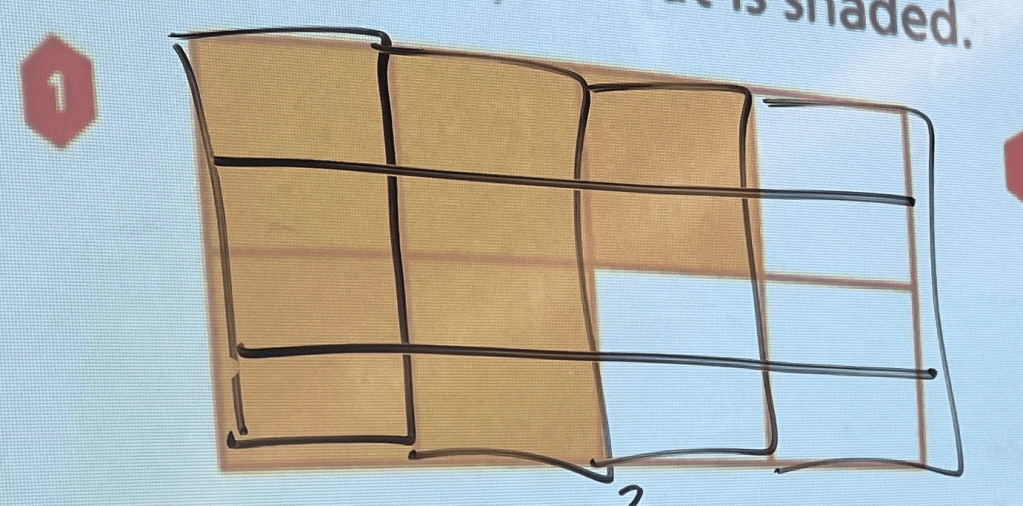

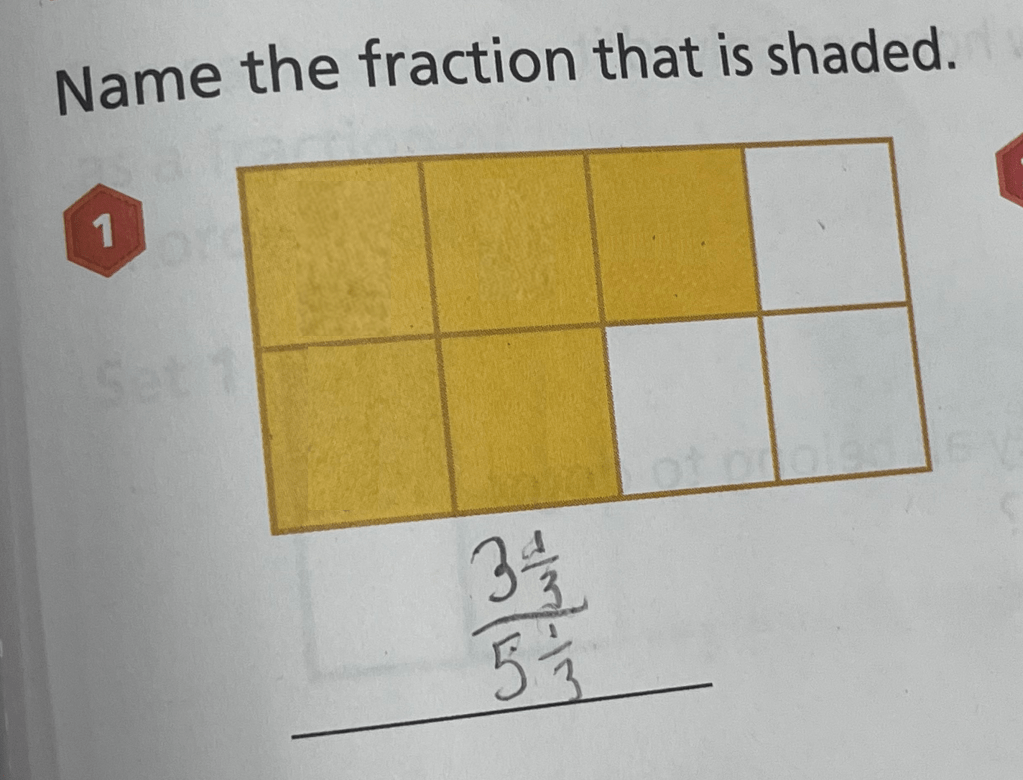

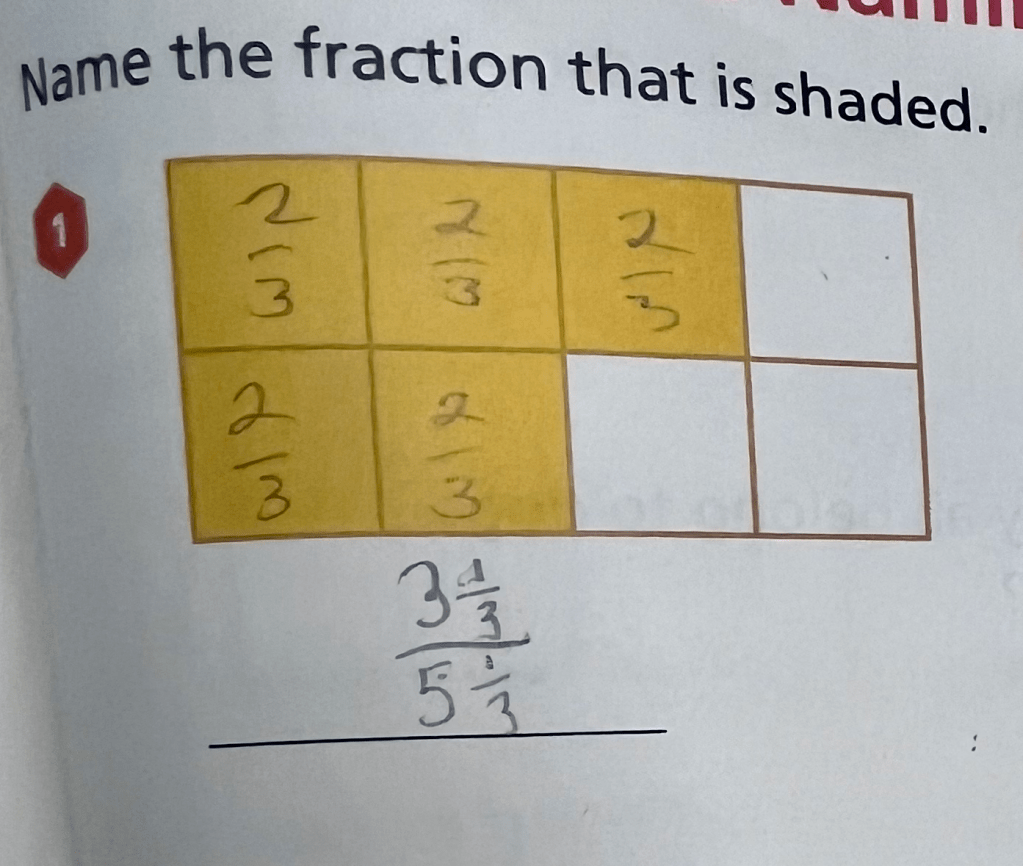

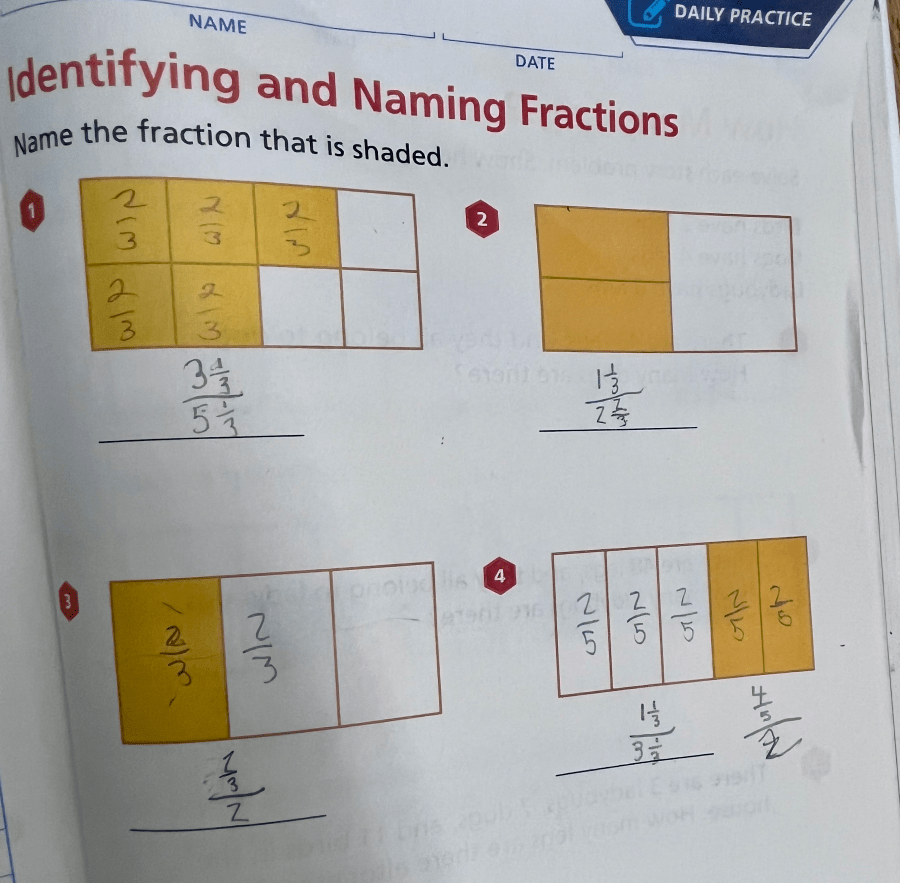

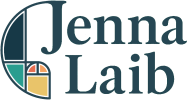

Then, we used a page in the Investigations workbook that had been marked for daily practice in a previous lesson. It showed several rectangular models for fractions, and asked students to name the fraction.

“What if we ask them to name at least two fractions for each figure?” I asked the classroom teacher.

“Yes! I think some students still need to make sense by partitioning the visuals,” she added.

Dealing with Unequally Partitioned Shapes

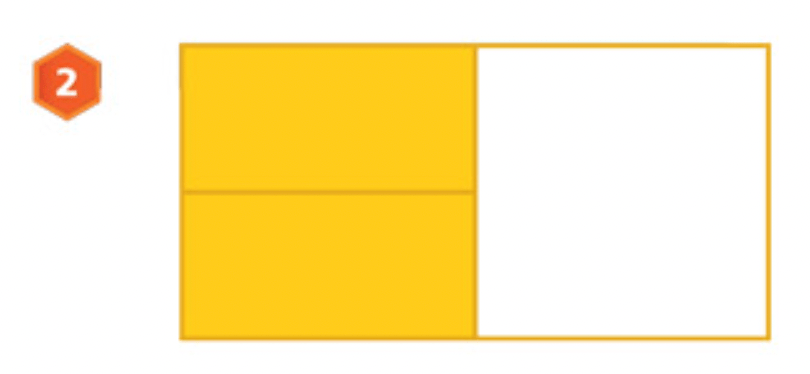

Three of the four figures on the page were equally partitioned (e.g. congruent thirds, with one of them shaded in). The last one looked like this:

I recorded student responses on the board:

. . . .

. . . .

. . . .

. . . .

. . . .

That last one came from Owen. I hadn’t even checked in with him, but I was curious about how he’d generated that fraction. Did he choose a numerator, and then double it to make the denominator? How did he come to choose ?

We pushed the students to show each fraction in the diagram. Students came up to the board to show their evidence. Where do we see ? How about

? How about

? (Spoiler: we don’t! Let’s cross that out.)

After the class discussion, we gave the students one last problem to work on, during which time I checked in with Owen.

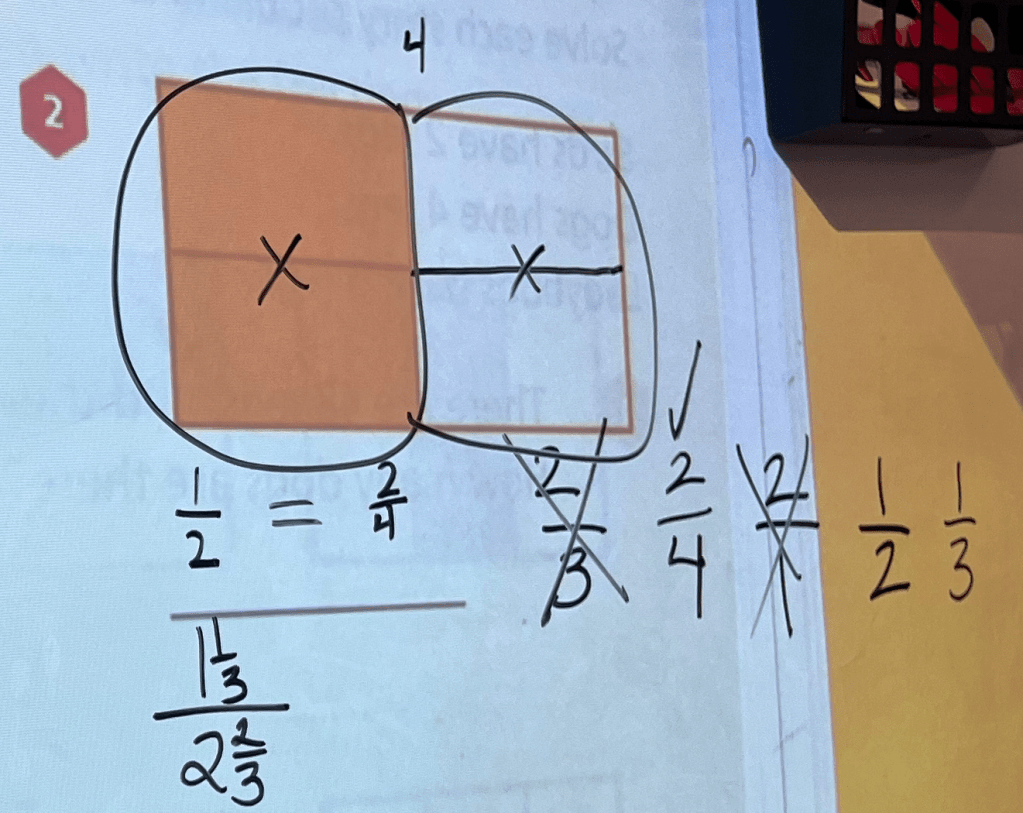

How did you come up with this fraction?

Most students wrote . If you partition each piece in half with a horizontal line, the sixteenths emerge.

But Owen wrote . In my head, I scaled the numerator and the denominator up by a factor of 3, to get… let’s see… oh, yes,

. I wondered if he had divided the numerator and then the denominator each by 3. Scale up, scale down.

So I asked him how he’d done it. “Well, like, instead of s, I did

s, so it’s five

s and that’s like

and

and…”

“Hold on, Owen.” The numbers were dancing my head. “So, like, you’re thinking of the parts as ?”

“Yeah, and then you can combine them to make …”

“Okay! Is it all right if I use your pencil? Sorry to slow you down. Your brain is working so fast, and I want to understand every little twist and turn. So you’re saying… these are all s.”

I recorded his thinking as best I could in the book.

It too me a second, but… yes, there was the .

“And then you have eight s to get the total of

.

Pretty genius.

What is Owen thinking about?

I thought he’d been messing around with proportional reasoning through scaling the answers up and down, but really he was messing around with proportional reasoning through the value of the unit.

This showed how Owen thinks about the fraction as a ratio. This isn’t simply , it’s

. Five groups of one thing out of eight groups of that same thing. This works for all real values of

.

I wonder how my knowledge of the common core standards (CCSS) also influenced this thinking.

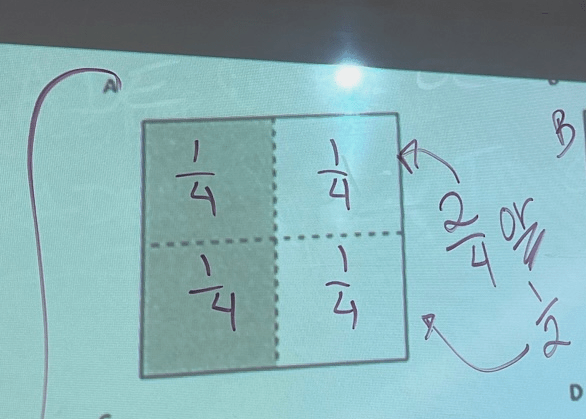

3.NF.A.1 Understand a fraction 1/b as the quantity formed by 1 part when a whole is partitioned into b equal parts; understand a fraction a/b as the quantity formed by a parts of size 1/b.

When dealing with area models for shapes, I sometimes label all of the parts like that:

Here, we have four parts that are all the same size — of the whole — and there are two

size pieces shaded, which is the same as

.

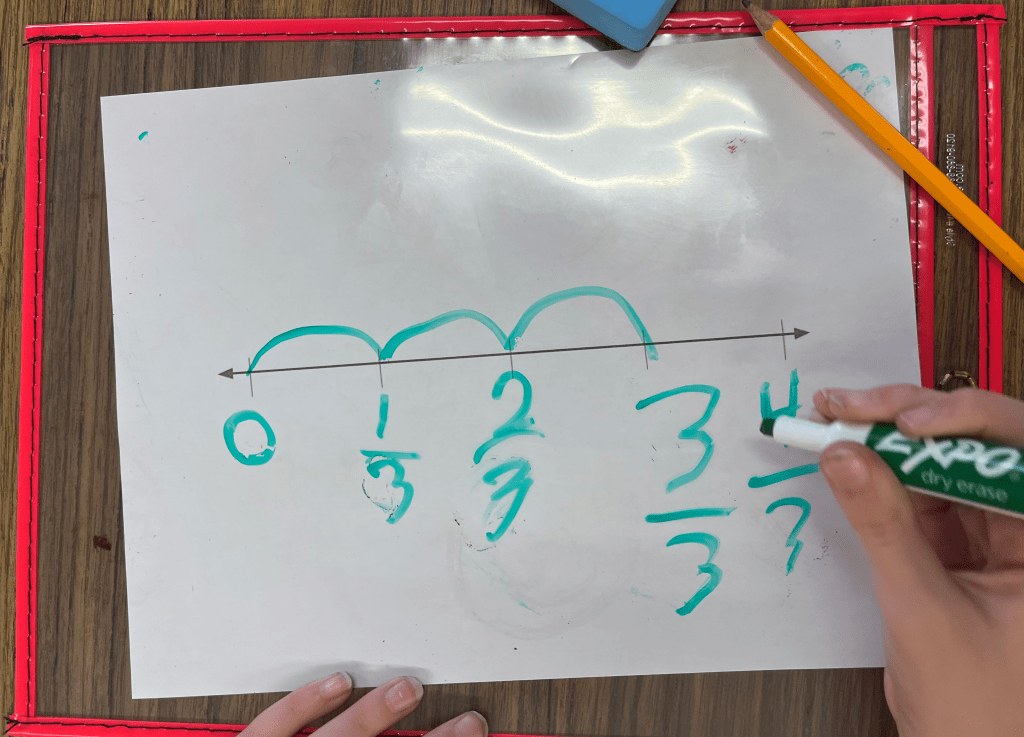

This looks a little different with other fractional representations, e.g. using a number line.

Here, we have . size jumps, and two jumps lands us at

.

So whatever sparked his thinking, Owen decided he wanted to play around with different values here.

Exploring Owen’s Thinking

“Can we record your thinking for some of the other problems?” I asked.

“I was mostly thinking about ,” Owen told me. He started to write in other values. “This one is

shaded, and then

not shaded, which means it’s

in all… and that’s just 2.”

“That’s interesting that your first two fractions — the ones on the top — have a fraction in the numerator and a fraction in the denominator.”

“Is that okay?”

“Absolutely! It’s called a complex fraction. We don’t use them a lot in third grade, but it’s so cool that you stumbled on them!”

“I like them!”

“But then your third one doesn’t have a fraction in both the numerator and the denominator.”

“Yeah, it doesn’t. Okay, so…”

I had started to wonder about when we could use Owen’s strategy to reveal equivalent fractions with whole number numerator and denominators, but Owen had already moved on.

“So I used in the last one, too, but then I wanted to make an equivalent fraction, so I also did

and then I got

,” Owen stated proudly. “I was surprised that it’s just 2, but it worked.”

“I love that! How did you decide to use the for the last one?”

“Well, I guess because it was already …”

“Yeah! I bet there are some interesting patterns to notice in there!”

I wanted to explore those patterns with him, or look for times that the math seems like it might “break” — like when using negative numbers — but it was already time for the class to go to lunch.

In Reflection

What encourages students to run with these divergent ideas? Last year, I wrote a blog post about enthusiasm and creativity in another third grade class (“Secret Squares and Stop Signs,” June 28, 2022). In this post, I identified four elements that made that lesson feel like such a success:

- The classroom teacher’s pedagogical knowledge

- The classroom teacher’s content knowledge.

- The classroom teacher’s pedagogical content knowledge

- The classroom teacher’s genuine curiosity.

I think these four elements were present in my interactions with Owen, and it feels impossible to undersell the power of being excited.

Why am I so excited?

Getting to grapple with creative ideas from students pushes my content knowledge, and satisfies my own desire for novelty. I love trying to figure out how a student’s thinking — the more convoluted, the better! — works. What connections can I make to other mathematical ideas? How can I prove why it works? How can I prove why it works succinctly and clearly?

What does excitement look like?

I crouch down next to the students. I listen to them, and ask questions to clarify both my understanding and also their communication of their ideas. I share my enthusiasm! I often ask to take a photo, so I can remember all of their cool thinking. This small action — asking to document their work — shows that I value it, quite genuinely. (And I do!)

What are implications for the classroom?

How do we encourage creative thinking in the classroom?

I think that the task matters. But beyond that, there seem to be some elements that help encourage creative thinking (without encouraging lots and lots of extra planning time). In Owen’s case, it helped to have a teacher who is genuinely curious, who shows enthusiasm, and who has a strong mathematical background in order to engage with these ideas. We take these ideas seriously.

The whispered challenges feel like a personal invitation to the students. They’re almost a dare, beckoning them to engage with new mathematics. For many students, this works a lot better than announcing to the class “when you finish with the problem, here’s how you can go deeper.” It ignites a spark.

However, I also worry about issues of equity. Teachers have implicit bias. How do we decide who we invite into challenge? If we offer a quick challenge to one student, how can we make certain others have access to the same thinking? Leaving it up to chance — one student’s ideas sparking another — means that some students get left out.

As the other students prepared for lunch, I saw Owen sharing his idea with another classmate, who offered pursed lips and a look of bemusement as he listened to Owen’s unitizing strategy. Another spark?

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Got this when I clicked the link. Ah, technology. [image: image.png]

LikeLike