Throughout my preservice teacher program, there were many conversations about “capitalizing on the teachable moment.” They were mystical — cinematic, even. At some point, good fortune would smile on you, and you’d be blessed with some totally outside the box thinking from a student, and you’d push all of the papers off your desk and say, “YES. Genius! Let’s go with that!” Meanwhile, as a teacher, pushing everything off my desk is not worth the mess it creates. More importantly, I see opportunities to use student thinking everywhere I look, in every lesson. There isn’t one magical moment that I’m waiting for: there’s countless opportunities, and we can orchestrate them.

In “The Case of the Impossible Triangles,” I wrote about a decision I had to make during a third grade class: would I follow the interesting detour? Or would that take us too far off course from the intended goals of the lesson? (And do we always stick to the intended goals, or is there reason to broaden or change them mid-lesson?)

Here’s how this played out this week, in a lesson in 8th grade.

Potential Detour #1: Area of Circles

On Monday, we launched a new unit about exponents and scientific notation. Early on in the lesson (from Desmos 6-A1 Math), students encounter the follow animation. We asked them they noticed and wondered.

Students wrote that they noticed things like:

- They’re doubling.

- The dots are splitting.

- It looks like cell division.

- The number of circles is multiplying by 2 every time.

Students wrote that they wondered:

- How many circles will be in stage 5

- Is there a way to write this out with exponents

Hahahaha, these two students are clearly no stranger to math class. These are the most math teacher-y wonderings, and I’m totally fine with it. They’re primed to go.

However, students further wondered:

- How small will the circles get

- Do all of the stages have the same area?

Students would see an interactive a few screens away with pinprick circles for stage 12.But did the splitting of the circles persevere the total area covered?

The classroom teacher and I considered our goals for the day. This was early on in the lesson, and we wanted to make certain that had lots of time to activate prior learning and process ideas about exponents before we taught the next lesson, equivalent expressions with exponents. The detour was interesting to me — and we’d get to review calculating the area of a circle! — but we wanted them to focus on exponents. This detour would distract from the big idea, and it’s particularly bad to do this in a lesson that’s designed to activate learning that students will need for this unit.

The verdict? Stay the course.

The classroom teacher shared the idea briefly with students, but then kept going onto the next few screens, where students would determine the total number of circles in different stages.

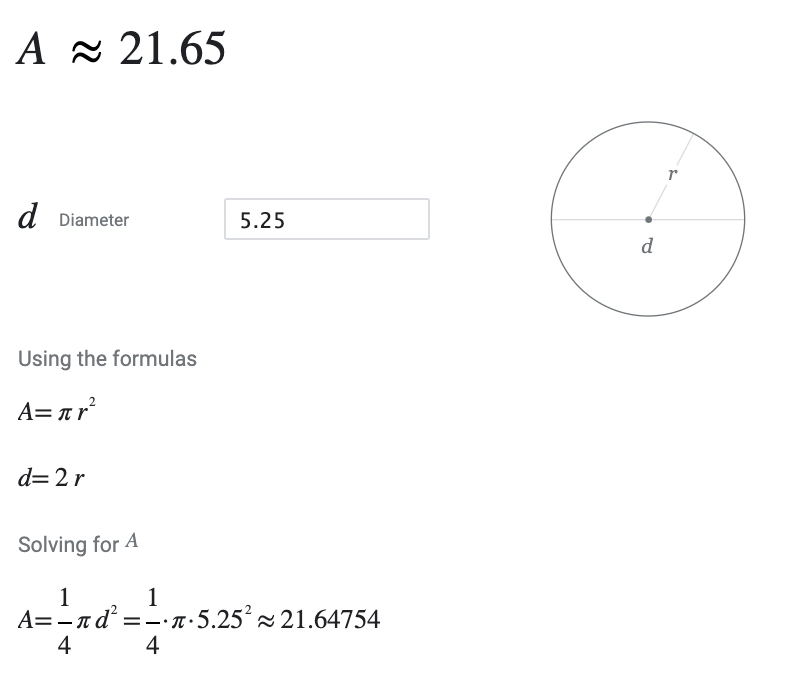

Still, I started to measure the size of a few circles using a ruler. I figured I could spare a minute or two for my own curiosity. The largest circle (stage 0?) seemed to have a diameter of inches, and thus a radius of

. So the area…

Confession: I knew I had about 2 minutes to explore this while the students were working, so instead of computing things myself, I googled “area of a circle with a diameter of 5.25.”

I measured the diameter of the next circle. It seemed to be about inches, which made for an area of approximately 11 per circle… wait. Maybe the area really was the same.

I arrived at a diameter of for the next stage, which had 4 circles, yielding an area of 5.41, or a total area of 21.64. Those Desmos engineers! Keeping us on our toes! While my measurements were not terribly careful, I decided that, yes, the total area seemed to remain constant even as the total number of circles increased by a power of 2.

Potential Detour #2: Do we multiply by 3?

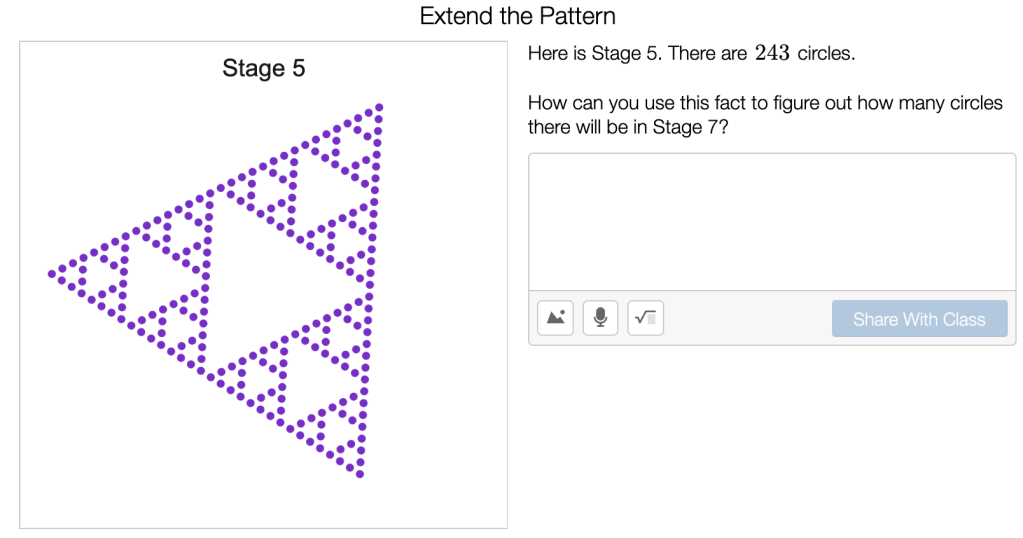

Later on in the lesson, students encounter another dot pattern that generates a design that looks like Sierpinski’s Triangle. After recording some ideas, and writing some expressions, students are asked to extend their thinking to move from stage 5 (which had circles) to stage 7.

I selected three student responses to share.

We examined the recursive reasoning of these students, and the different way that they recorded it.

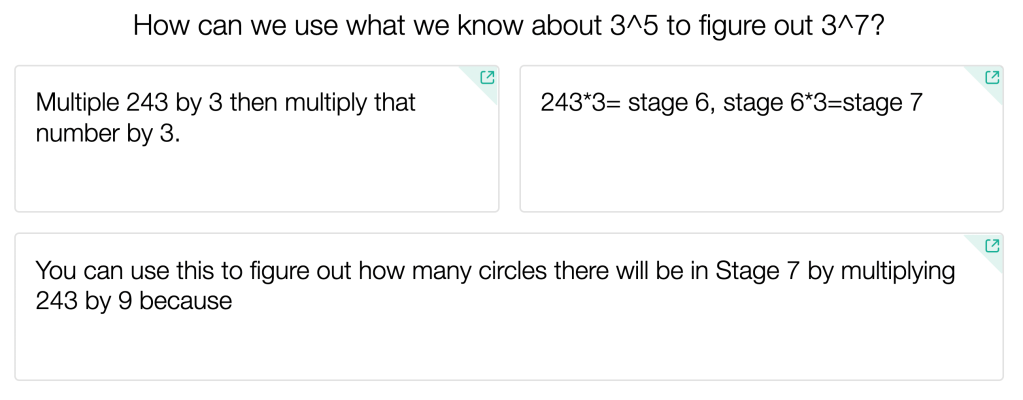

“Okay, so the bottom response is from Snehal, and she didn’t finish what she was writing. Let’s help her finish it. And where is that 9 coming from. I don’t see a 9 anywhere else… “

Lucas raised his hand. Oh, it’s coming from the Instead of multiplying by 3 and then again by 3, I guess we could just multiply by 9 as a shortcut.”

I love a good shortcut!

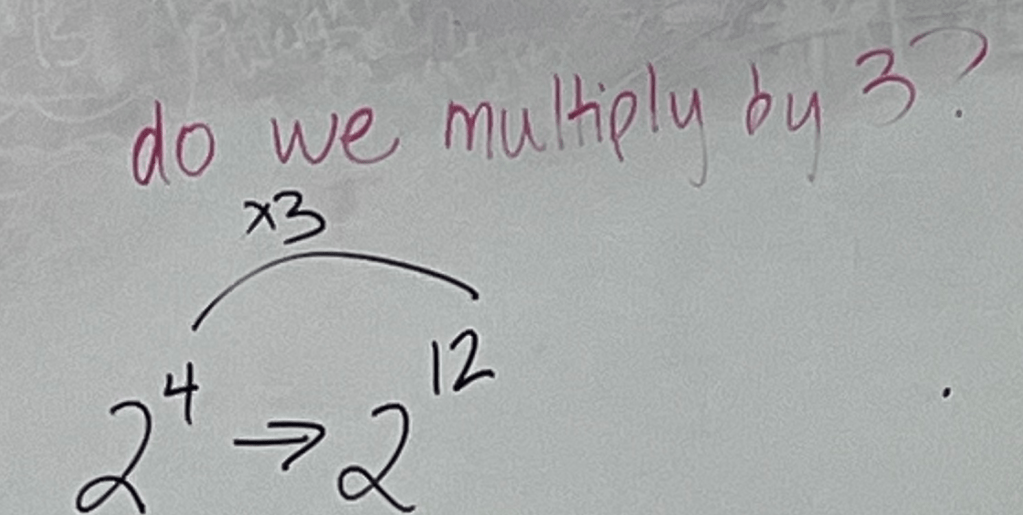

Sadie, at the back table, raised her hand. “Wait, so in the first circle problem, we went from to

. So… like… 12 is three times bigger than 4. Could we have just multiplied by three?” Another potential detour.

The verdict? Going down this detour would actually preview the next day’s lesson, about equivalent expressions, so: absolutely! I turned off the projector, and asked students to face their chromebooks away from them.

“Oh! I love this question, Sadie! Brilliant. Let’s explore it!”

Pushing Thinking with the ‘Detour’

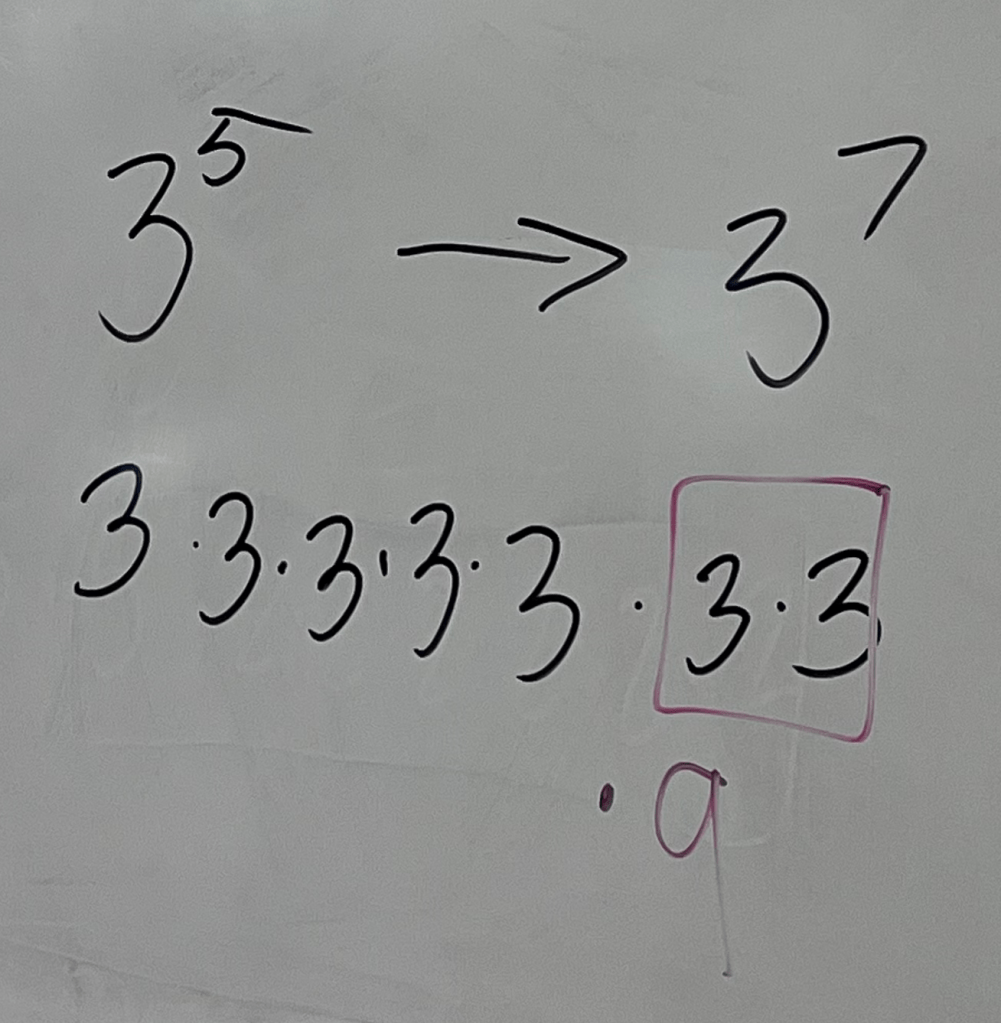

I recorded a facsimile of Sadie’s thinking on the board.

I asked students to think independently about this inquiry for 15-20 seconds, and then they’d have time to talk with others at their table. Mason started talking almost immediately with the girls sitting near him.

“Okay, but before we were just dealing with numbers with no exponents, but this time we’re dealing with just the exponent part of the number,” he whispered.

“Oh, you’re right,” Olivia nodded. “But also last time we were combining the numbers, and this time we’re just multiplying, so maybe..?”

I let students converse for another few seconds. “Anyone have any initial thoughts to share? Mason, I heard you and Olivia say some interesting things…”

Mason sighed, but he shared, patiently. “Okay, so I noticed that last time we were dealing with just the base part of the number, and now we’re dealing with the exponent part of the number, and I think they probably work different.”

“Interesting! Okay, so let’s figure out if they work differently. Grab a whiteboard and a marker.” These materials are always available at the center of every table group. “See if you can work it out. What is happening? How can we use what we know about to figure out the value of

?

I recorded when we multiply the exponent by 3… on the board as they worked.

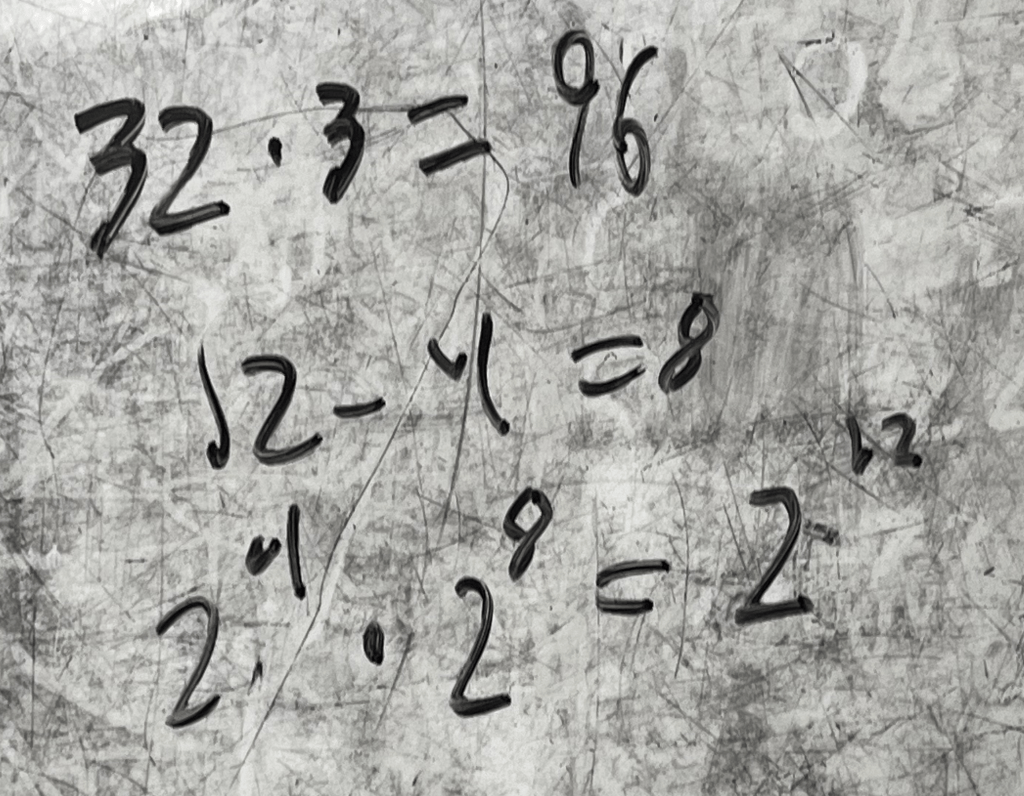

This was Lucas’s board.

“Okay, so… is 32, and

, so multiplying by three didn’t work,” Lucas told me. (Never mind that

, something we’d discuss later.)

He then wrote .

“Okay, so we want to have 12 twos multiplied together, and we already did 4 twos multiplied together… so we need to do 8 more twos.

He recorded .

I observed another two students at work, and then called the class back together. I let Sadie share first. She’d already uncovered that this didn’t work, and I can appreciate giving middle schoolers a chance to save face.

“Multiplying by three definitely doesn’t work,” Sadie shared. “It’s way too small. 16 times 3 won’t get to 4,096.”

I held up my phone, and pressed the button to initiate siri. “How much is ?” I asked crisply.

“It’s 256.” came the response.

“Okay, so we need to multiply by 256. Where is that 256 coming from?” I pushed.

“2, 4, 8, 16…” I heard Zahra mumble.

“Let’s write out those powers of two!” I recorded a long string of multiplied twos on the board, and then counted aloud. “2, 4, 8, 16, 32, 64, 128, 256… It looks like 256 is the same as…”

“Two to the eighth!” Mason exclaimed. “Oh, that makes sense!”

I smiled. “Why does it make sense?”

“Because 4 + 8 =12, and we want to get twelve twos,” he responded. “So we need eight more.”

“This is exactly what we’re going to be working on tomorrow!” I exclaimed. “So you already have a head start. We’ll be working on equivalent expressions: decomposing terms, combining terms… you’re going to be fantastic. In the meantime, I’m going to unpause you on Desmos, so turn your chromebooks back around…”

When do we take the detour?

Due to some oddball scheduling and some field trips, I taught this lesson three times this week. (This is something middle school classroom teachers do every day, and sometimes I rarely get the chance to do.) In every class, a student offered some permutation of the “will these circles add up to the same area?” wondering, and every single time I didn’t take the class down that detour.

So how do we decide when we want to diverge from the lesson?

I will often share interesting ideas the class has without taking us in that direction, but not every time will it become the focus.

When making the decision, I consider some of the following questions:

- What is the intended learning for the day?

- When is the purpose of this lesson? (e.g. introduce a new idea, activate prior learning, extend and apply concepts, etc.)

- Will we address this idea later? (sometimes, it’s a helpful preview! Sometimes, due to other constraints, it’s better to wait)

- How long do I anticipate spending on the detour?

- How much time do we have left in the block?

- Do other students have access to engage with this idea? Will they find it interesting?

- Will the conversation develop student thinking and push their ideas forward?

So there’s issues of curricular coherence, time, student engagement… and that’s the tip of the iceberg. This is hardly an exhaustive list.

Meanwhile, in a third grade class later that day, we were making similar considerations as we considered a student’s strategy for finding equivalent fractions. Fascinating! Accurate! Very complicated! But we were short on time, and we definitely needed a lot of time in order to support students in accessing his idea.

_________________________________

I think if you’d told my 21-year-old self that I’d see these magical “teachable moments” every single day, I would assume that my future self had gotten a job teaching alongside Robin Williams in the Dead Poets Society. But, instead, I believe there’s real power in looking and listening for the power and depth in student ideas everywhere. What are students thinking about? Then: when and how do we leverage these thoughts?

Discover more from Jenna Laib

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I always like finding chances to “take the scenic route” in my math teaching, and sometimes we save those moments in a “parking lot” until we have time to pursue the detours. Thanks for highlighting some things teachers can consider when deciding.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes! I love the idea of a parking lot! I am historically bad at returning to those in K-12. 😂 I’m better during PD sessions where I build in time.

LikeLike